In this supplemented learning section, discover the meaning of Victorian Christmas and why it is so relevant to our modern-day Christmas. Some traditions from the previous section will reappear with more in-depth analyses and some completely new traditions will be introduced.

Learn about the buildup to what we now call a Victorian Christmas, why it happened, and how it happened.

A Victorian Christmas

Christmas Before

Before the Victorian era, December 25th was just another day to many of the middle and lower classes who worked through December without any days off. There was just no time to celebrate, unless you were a member of the wealthy upper class.

Christmas did not start off as a visible, commercialized holiday. Homes were only sparsely decorated and you never saw Christmas decorations in businesses, public places, or advertisements. There were also no Christmas trees, no Christmas cards, no Santa Claus or Father Christmas, and rarely any public festivals dedicated to the holiday. At the beginning of the 19th Century, Christmas was a privately celebrated religious holiday. This meant people who celebrated went to church, had a few handmade decorations in their homes, and ate a meal with family and friends.

Developing the Victorian Christmas

It was during the Victorian era that Britain moved into the second Industrial Revolution, just decades after the first had ended. Both revolutions (especially the second one) were characterized by mass advances in technology, infrastructure, and industrialization. This meant that new machines were invented and/or improved upon to produce goods faster, cheaper, and in higher quantities.

In order to protect workers, a new set of laws known collectively as the Factory Act, was introduced to Britain in 1833. This act gave the working class a set number of days off during the year, which included Christmas. For many, this was something that they never had before and it became an incentive to celebrate the rising holiday.

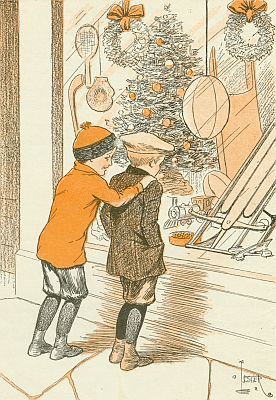

More imported and local goods became readily available to the public at a rapid pace due to the industrial revolution. Companies started to see Christmas as an opportunity to make a profit from new and mass-produced goods. This commercialization led to a swift re-invention of the holiday.

Christmas and its new traditions were soon incorporated into ads for various businesses that wanted to take participate in the holiday season. This transferred Christmas from the private to the public sphere as decorations and celebrations started appearing in businesses.

Most of the advertised traditions were motivated by profit for companies, resulting in widespread advertisements and store window displays. The selling of Christmas crackers, cards and decorations, while entertaining shoppers with pantomimes and visits with Santa Claus helped generate wealth for businesses, giving them an incentive to capitalize on Christmas through the spread of Christmas cheer.

|

|

|

The Meaning of Christmas?

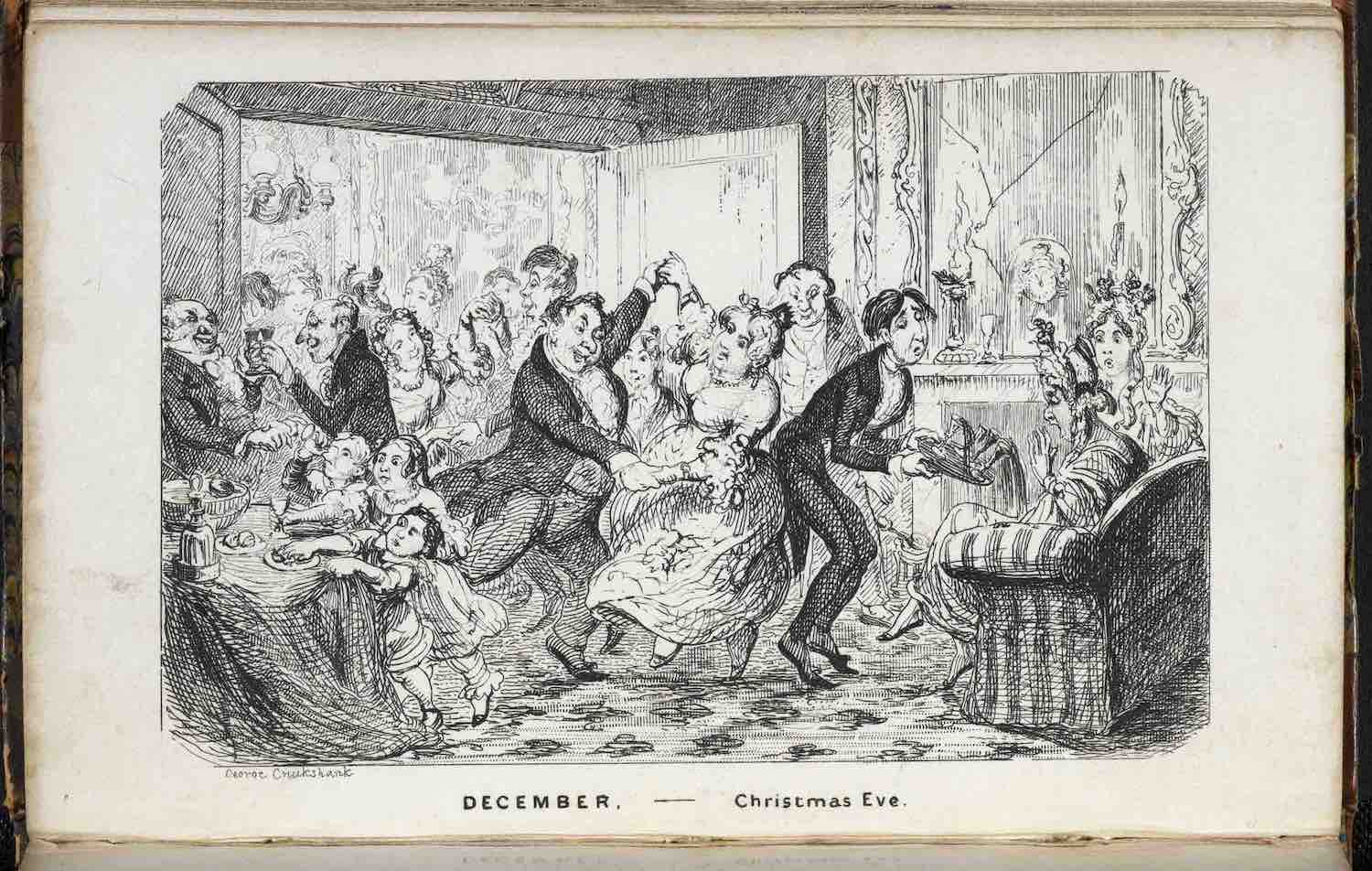

During the Victorian era, Christmas quickly became visibly secularized from the original nativity. There were many new and re-invented traditions that appeared, which had nothing to do with Christianity or other religious customs. Although attending church mass and celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ was still very central to the holiday, it was no longer the only way to celebrate.

During the Victorian era, Christmas quickly became visibly secularized from the original nativity. There were many new and re-invented traditions that appeared, which had nothing to do with Christianity or other religious customs. Although attending church mass and celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ was still very central to the holiday, it was no longer the only way to celebrate.

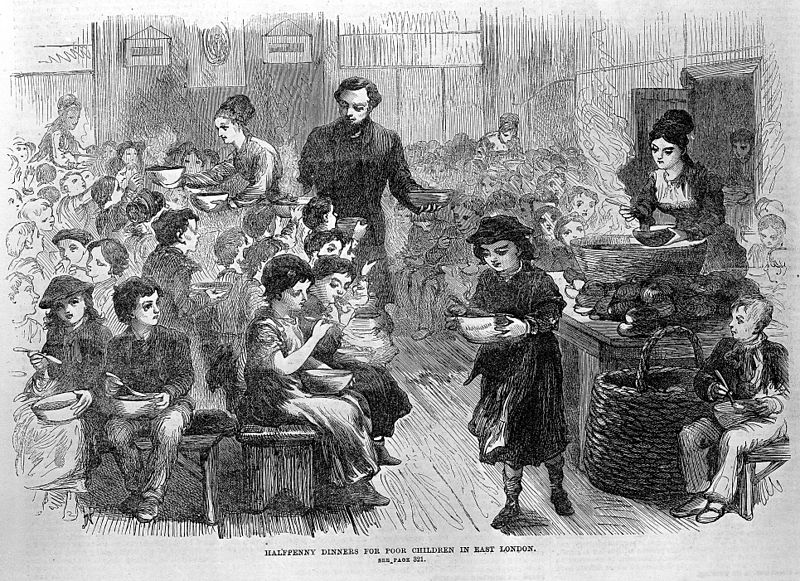

Christmas also became an annual opportunity for lower classes to experience higher-class living by indulging in rich foods, material items, and parties. Charity had always been a major part of Christmas and continued to be throughout the Victorian era. Wealthy individuals were encouraged to donate their time and/or money to the lower classes around the holidays to promote good Christmas spirit. Many organizations also provided Christmas dinners for the poor.

|

|

|

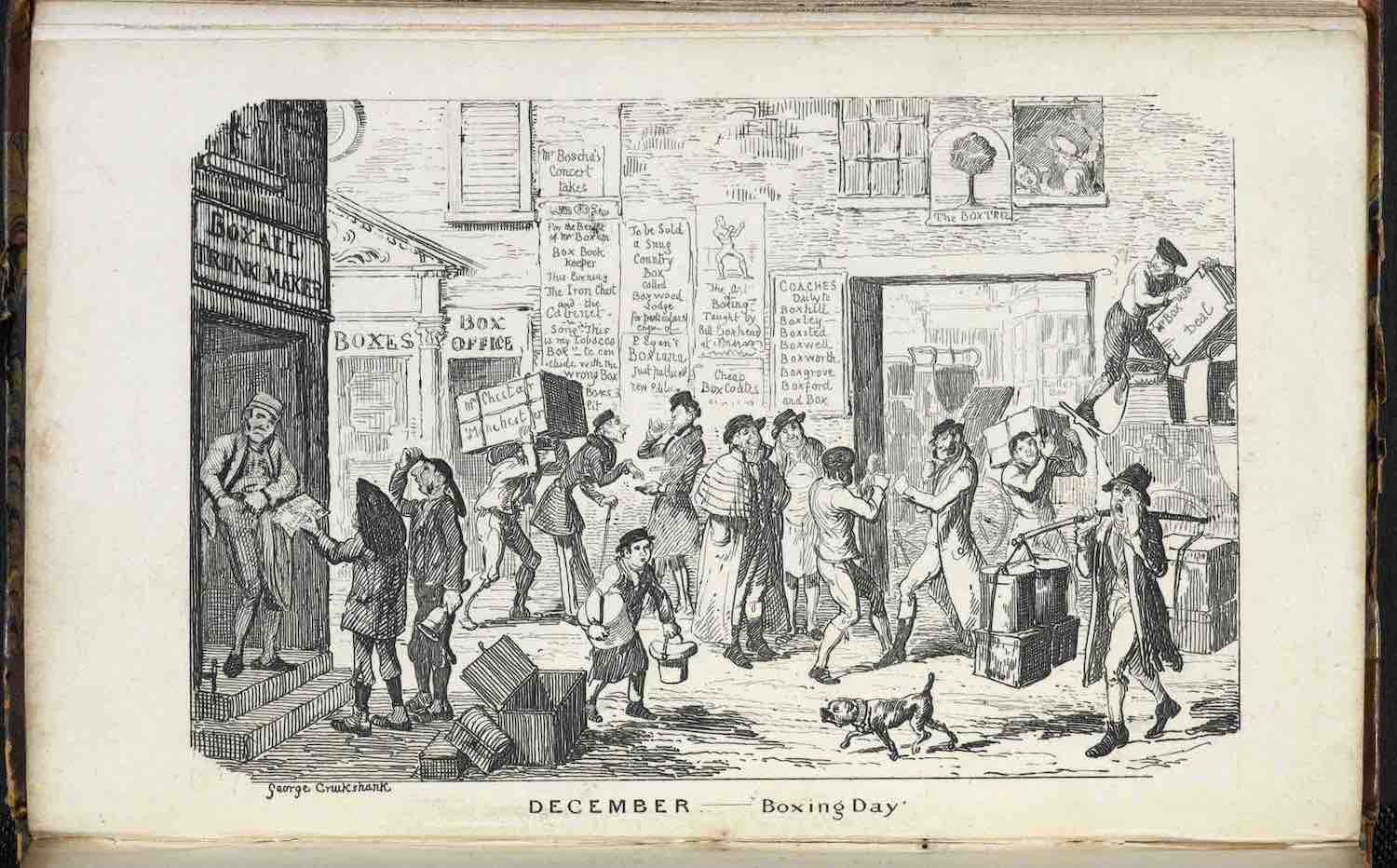

Boxing Day

The day after Christmas, most commonly referred to as “Boxing Day,” earned its nickname during the Victorian era. While the exact origin of the day's traditions are unclear, various theories suggest the date is marked by charity and encompassed the Christmas spirit of giving.

The day after Christmas, most commonly referred to as “Boxing Day,” earned its nickname during the Victorian era. While the exact origin of the day's traditions are unclear, various theories suggest the date is marked by charity and encompassed the Christmas spirit of giving.

For centuries, December 26th was a day of celebration for poor and working class families, especially those who worked on Christmas Day as servants preparing for their employer's celebrations. On the 26th, employers gifted their employees with boxes containing money, leftover food, and small gifts as an appreciation for their service. Wealthy individuals often provided the same boxed gifts for the poor. These Christmas bonuses were encouraged acts of charity that contributed to the name 'Boxing Day'.

December 26th is also known as the day of St. Stephan's feast, a tribute to the first Christian martyr, which is most commonly celebrated in Ireland. St. Stephan was one of seven deacons, who was well known for his work in charity. He distributed the contents of alms boxes to the poor, which became a common church activity during the Christmas season.

Throughout December, alms boxes were used by churches to collect offerings from the congregation. Those who could afford to give spare change were encouraged to do so. On December 26th, clergy members would divide up the donations and distribute them to the poor. These alms boxes may have also contributed to the name 'Boxing Day'.

Decorations and Entertainment

Decorations

As communication and visual culture expanded with industrialization consumers were encouraged to decorate with elegance, through the introduction of uniform styles and traditional decorations, both handmade and mass produced.

As communication and visual culture expanded with industrialization consumers were encouraged to decorate with elegance, through the introduction of uniform styles and traditional decorations, both handmade and mass produced.

In the late 19th Century, the desire for elegance turned into a push toward expensive and stylized aesthetics. Magazine articles and advertisements advised against the use of previously enjoyed decorations such as tinsel or paper banners, which were now considered tacky or cheap.

Suggested new alternatives such as elaborate prints and complex embroidery were costly; however, Christmas decorations were meant to represent a season of indulgence and commercialization. Of course this norm could be followed only by those who could afford it.

Blown-glass ornaments were popular decorations available for purchase after 1870. Industrial transport made this possible as they were produced in Germany and Bohemia before making their way to Britain, USA, and Canada. Blown-glass shops like this also produced and shipped out tinsel, cast lead in the shape of stars and crosses, and made paper ornaments for distribution.

DID YOU KNOW? The first ads for mass-produced tree ornaments appeared in 1853.

Christmas Tree

The Christmas tree became an important Victorian tradition, originating from Germany. Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert is given credit for bringing the tradition over to England; however, in reality, many Germanic settlers had brought the tradition with them long before him. It was the adoption of the practice by the Royal Family that cause the tradition to spread rapidly throughout England, the United States, and what would become Canada.

The Christmas tree became an important Victorian tradition, originating from Germany. Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert is given credit for bringing the tradition over to England; however, in reality, many Germanic settlers had brought the tradition with them long before him. It was the adoption of the practice by the Royal Family that cause the tradition to spread rapidly throughout England, the United States, and what would become Canada.

The tradition of worshipping a tree as a symbol of eternal life goes back to ancient times, but the first Christmas tree was recorded in 17th Century, Germany. It was a paradise tree (fir tree) with wafers (cookie-like food items) and apples hung from the branches to symbolize redemption, based on the biblical story of Adam and Eve. As the adoption of the tree spread to other countries (including England in the 19th Century), the symbolic nature varied and became more secularized. For many adults the tree became a symbol of childhood customs and family.

Caroling

The Victorians re-popularized the centuries-old tradition of Christmas caroling with new and newly translated songs that encouraged participation.

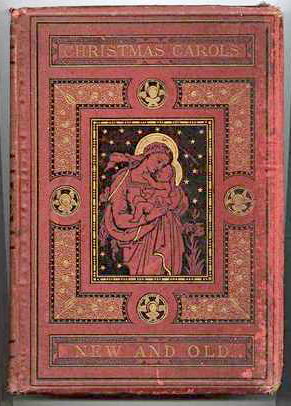

Christmas carols started off as interpretations of the original Christmas story that were sung in various rhythms. Most songs emphasized Christian beliefs but were meant to spread joy and cheer around the holiday. During the Victorian era, many new carols were written and a heavier focus was placed on cheer and feasting, rather than religion.

Anthologies or collections of popular carols, both new and old, were compiled into books that became desired collectibles during the Victorian era. Beginning in December, carol lyrics were often provided in printed news outlets and magazines to share popular songs and encourage people to participate in the tradition.

|

|

Parlour Games – Snapdragon

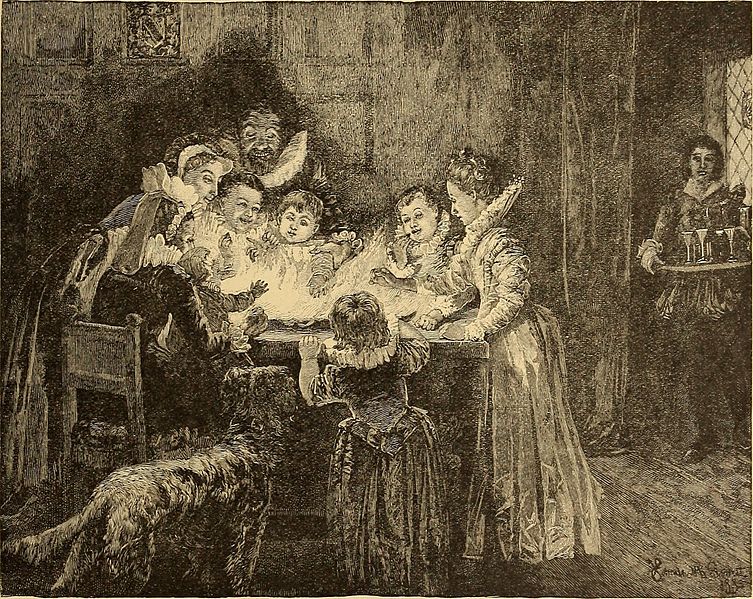

Snapdragon or Flap-dragon was a favourite, but very dangerous Victorian parlour game, which is no longer played. Please do not try this at home! The game started when all the family and friends gathered around a bowl filled with brandy (alcohol) and raisins. Someone would light the brandy on fire (which stayed burning because brandy is flammable) and the game started, accompanied by a chant. Every participant had to reach forward into the burning bowl, grab a small handful of raisins and put them in their mouths. The goal of the game was to consume the raisins without spitting them out or burning yourself, other players, or the playing space.

|

|

*Disclaimer: The Diefenbaker Canada Centre (DCC) accepts no responsibility or liability for participation in any of the activities described in this exhibit. Under no circumstances will the DCC be held responsible or liable in any way for claims, damages, losses, expenses, costs or liabilities whatsoever resulting or arising directly or indirectly from your participation in the exhibit activities or from your reliance on the information and materials provided. If you choose to participate in any of the activities you do so at your own discretion and risk.

Yule Logs

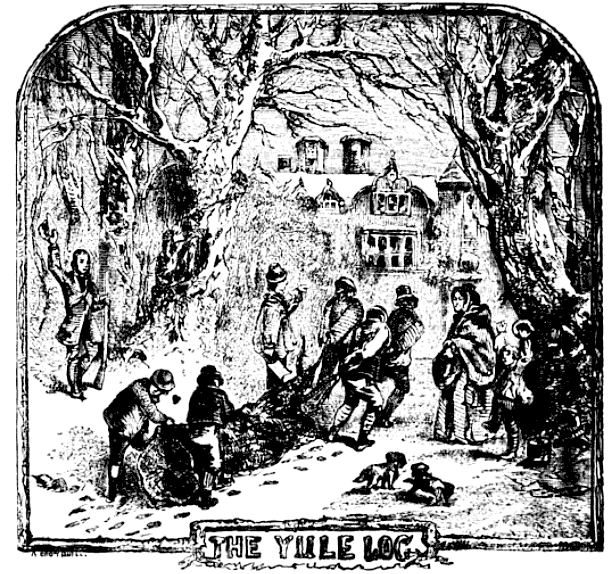

The Yule log is a part of an ancient Scandinavian tradition that is rooted in winter festivals. Each year, families would go out and collect a massive log that required several people to drag indoors. Once inside, the log would be burned for 12 days combining the ash from the previous year’s log.

As the custom began to spread across Europe, each country incorporated their own unique symbolism into the tradition of collecting, preparing, and burning the Yule log.

The Victorian Yule log tradition was re-adapted into a 12-hour log burning instead of 12 days.

|

|

Food and Gifting

Feasting

Feasting at Christmas time was nothing new to the Victorians as the tradition of winter festivals dates back to the 4th Century. Even today, it is a time for families, friends, and communities to gather and strengthen their social bonds over a shared meal.

Feasting at Christmas time was nothing new to the Victorians as the tradition of winter festivals dates back to the 4th Century. Even today, it is a time for families, friends, and communities to gather and strengthen their social bonds over a shared meal.

Feasts were not limited to the wealthy, as all classes took part in the tradition in some form, eating the best foods they could afford. The stratified Victorian society grew more transparent during feasts because the same foods were usually enjoyed by those of various classes.

Christmas became a well-known opportunity for people to indulge on not just gifts, but food as well. The holidays encouraged all people, regardless of social class, to enjoy large meals, which included expensive and rare food items. While the wealthy indulged in exotic foods that were inaccessible to the lower classes, both experienced tasting foods they normally didn't eat. Feasting on rich foods was seen as one of the most important traditions at Christmastime.

Sweets and Candy Shops

The popularity of sweets and candies increased dramatically during the Victorian era due to the increased accessibility and affordability that came with industrialization. New machinery and technology improved the transportation of raw goods, allowing sweets to be made faster, at higher quantities and promoted new candy shop creations. Prior to this, limited varieties of sweets were a luxury enjoyed by the wealthy; now all the classes could have a taste.

The popularity of sweets and candies increased dramatically during the Victorian era due to the increased accessibility and affordability that came with industrialization. New machinery and technology improved the transportation of raw goods, allowing sweets to be made faster, at higher quantities and promoted new candy shop creations. Prior to this, limited varieties of sweets were a luxury enjoyed by the wealthy; now all the classes could have a taste.

Christmastime encouraged people to purchase sweets, because it was known as a holiday to enjoy special luxuries.

As the Victorian era progressed and the popularity of sweets grew with new flavours and inventions, specialty confectionary shops dedicated wholly to candy and sugary sweets started popping up all over.

Candy makers usually tried to save as much money as possible. They would often disguise the fact that they replaced main ingredients with cheaper substitutions. For example, if a recipe called for almonds, candy makers could substitute discarded fruit pits. Some other popular ingredient substitutes were alum, lime, bullock blood, charcoal, acetate of soda, and oxide of lead (which they didn’t know was poisonous at the time).

DID YOU KNOW? Licorice allsorts were created in 1899 when a salesman dropped a tray of sweets on the ground and they broke into many pieces. The customer loved them anyway and asked for more! From then on, they continued to be made and sold.

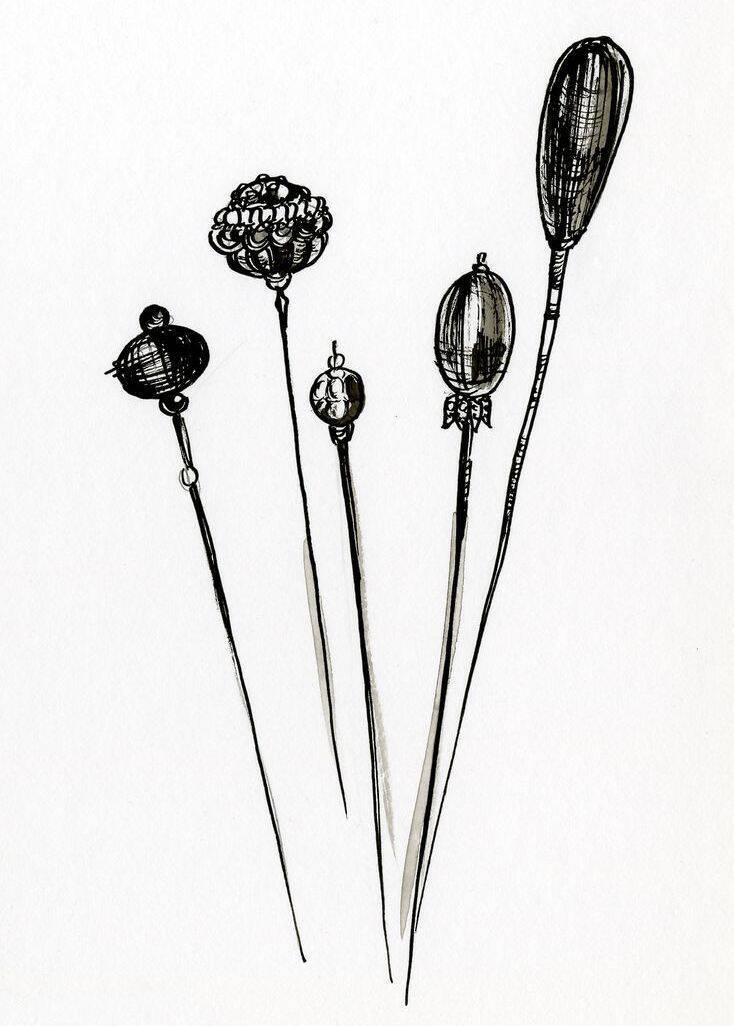

Adult Gift-Giving

With industrialization, store advertisements and department stores pushed for commercialized gifts to replace handmade ones. As companies realized how much money they could make from the Christmas season, they too jumped on the trend of promoting Christmas through elaborate window displays and ads designed to draw in customers.

What adults gifted each other depended on gender and relation; whether it be a lady gifting to her brother or a man gifting a woman he was courting. For those who were concerned with what was considered appropriate, magazines and etiquette books (for ladies) outlined the dos, don'ts, gift-giving, with helpful tips and suggestions.

Popular gifts for men from female relatives included shaving kits, pens, bought or embroidered sleep caps, smoking caps, slippers, tobacco pouches, and handkerchiefs. While purchasing gifts grew in popularity, it was considered more personable if women made something by hand, especially for their partners. It was considered inappropriate for a lady to give something to a male if she was not related, engaged, or married to him.

Popular gifts from men to women of close relation included scented soaps and perfumes, jewelry, and mending or knitting supplies. Gifting a lady of non-close relation often consisted of flowers, sweets or fruits.

|

|

|

Figures of Christmas

Christmas and the nativity had been closely intertwined leading into the Victorian era. As Christmas traditions became increasingly secularized, Jesus Christ was no longer the only figure celebrated on December 25th. A jolly figure known as Saint Nick would soon inspire new celebrations on December 25th, leading to the revolution of traditional characters and the creation of new winter figures.

In modern times, many of these figures have morphed into one common character with interchangeable names; however, most of these figures have their own unique tale of origin.

Saint Nicholas: The Man

The name Saint Nicholas refers to both a real man and a figure of creation inspired by the tradition of this man who would later inspire other figures of creation for the Christmas holidays. This is why their characters are interchangeable in many traditions.

Before he was a saint, Nicholas was a Christian who lived during the 4th century in what is now Turkey. He would later become a Bishop known for his charity after travelling far distances to aid the poor. Sometime after his death he was declared a saint to the vulnerable in society, including children. He died on December 6th, which became the day when people gathered annually to feast and celebrate his life. He is still celebrated to this day.

|

|

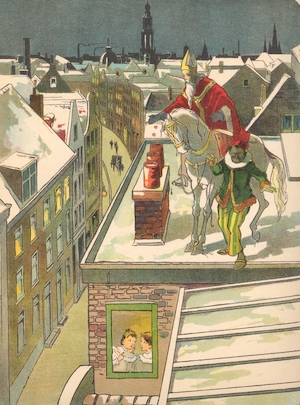

Sinterklaas/Saint Nicholas: The Figure

Sinterklaas is the Dutch figure of creation based on the life and tradition of Saint Nicholas. He closely resembles the dress of a bishop with a tall bishop’s hat, long red and white robes, and a long white beard. On the eve of Saint Nicholas’s feast, Sinterklaas would travel by horse or donkey and drop treats and toys down chimneys and fill shoes or clogs with sweets.

Sinterklaas is a Dutch translation of the name Saint Nicholas. Other Nordic countries who adopted the tradition of Saint Nicholas had their own names for him and similar traditions to that of Sinterklaas.

|

|

DID YOU KNOW? Krampus is the half goat, half demon companion of Saint Nicholas/ Sinterklaas whose story originated in 17th Century Germany. On the eve of the feast, he would accompany Sinterklaas and decide whether to reward or punish the children. Krampus was responsible for punishments and either hit kids with birch branches or kidnapped them!

Father Christmas

Father Christmas is an ancient English figure who has gone through multiple name, image, and tradition changes since his origin as a pagan winter festival character. Under various rulers of Britain, the figure morphed to fit ever-changing cultural beliefs and it wasn’t until the Norman ruling that Father Christmas and his associated traditions came to be known. At this time, imported stories of Sinterklaas and Saint Nicholas helped transform the winter figure into his modern version. Father Christmas was associated with December 25th though as opposed to Sinterklaas and Saint Nicholas who were still attached to December 6th. During the Victorian era, Father Christmas became the pinnacle figure of the Christmas holiday who delivered gifts and Christmas spirit to all.

|

|

|

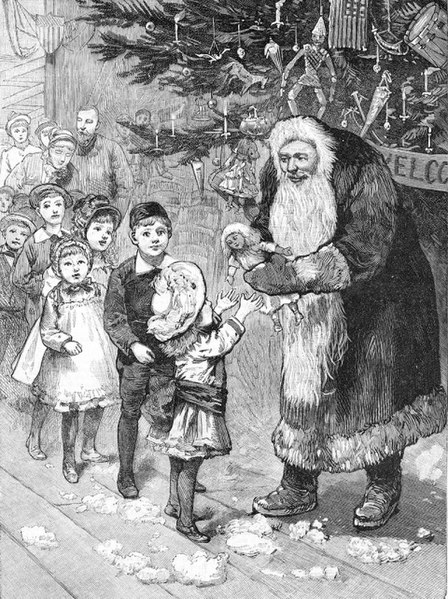

Santa Claus

Santa Claus is the most famous Christmas figure in modern Western tradition, thanks to his overbearing presence in advertisements and commercialism, which tightly intertwines him with the holiday.

His story began in the United States during the 19th Century, after Americans re-interpreted the stories of St. Nicholas and Sinterklaas brought over by Dutch and German settlers and combined them with local traditions, American Protestantism, and British-Victorian Christmas ideals.

|

|

|

While the figure of Santa Claus may have been adapted from Sinterklaas, there are distinct differences in his personality and dress. Unlike Sinterklaas and his companion Krampus, Santa Claus did not delve into harshly punishing children. Instead, Santa Claus uses a naughty or nice list to determine which children will receive gifts. The image of Santa was also left undecided for quite some time. He did not wear the traditional bishop robes and hat of Sinterklaas; instead, he was portrayed in a variety of different coloured robes, heights, and shapes.

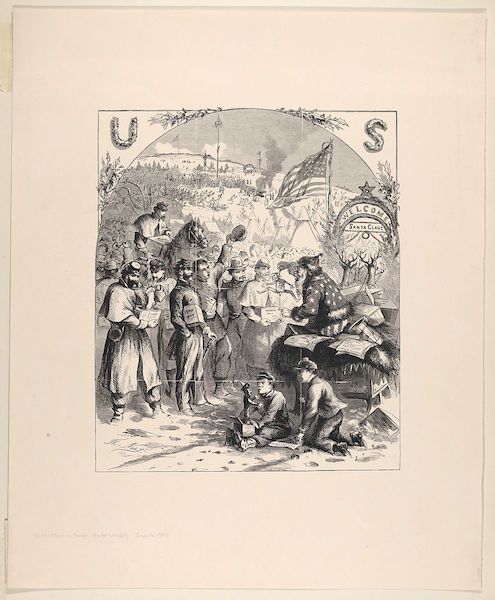

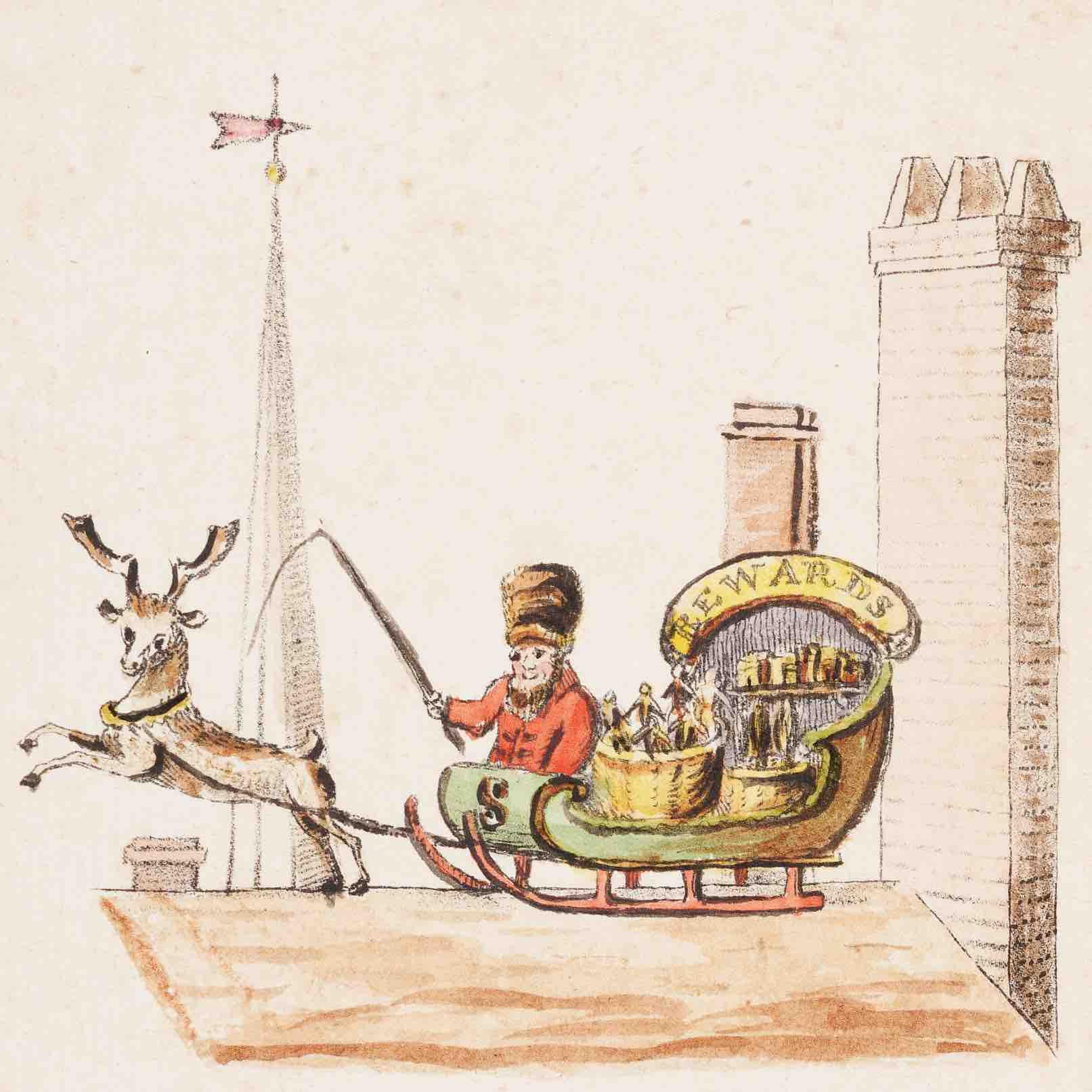

An 1821 poem, Old Santeclaus with Much Delight, was one of the first to illustrate a Santa figure delivering gifts on Christmas Eve rather than December 6th, as Sinterklaas does. The image also replaced the wagon of Sinterklaas with Santa’s sleigh. The famous poem, Twas the Night Before Christmas, published in 1823 as A Visit from Saint Nick, not only gave him a modern description, but also represented a pinnacle moment, which shifted Christmas enjoyment from adults to children. Clement Clarke Moore, the author, also named the eight reindeer who pulled the sleigh. Thomas Nast’s 1863 portrayal of Santa Claus in Harper’s Weekly gave him the occupation of not only delivering gifts but also Christmas spirit.

|

|

There is much debate as to who created the modern image of Santa Claus as a plump, rosy cheeked man with a white beard and a red suit, who spread cheer.

There is much debate as to who created the modern image of Santa Claus as a plump, rosy cheeked man with a white beard and a red suit, who spread cheer.

In 1931, long after the Victorian era, the Coca-Cola soda company used Santa Claus to advertise their products. The image of a plump, red suited, white bearded man was not new but up until this point, it had not been commercialized. With these new popular advertisements, the westernized image of Santa driving a sleigh was no longer a costumed variation; it was a permanent image.

Although many may credit the Coca-Cola Company with this image, they were not the first to envision him this way, so the credit may belong to multiple parties.

DID YOU KNOW? The name Santa Claus is said to have originated from the accent of New Yorkers pronouncing Sinterklaas.

Conclusion

The Victorian era saw a rapid re-invention of the Christmas holiday and traditions with industrialization, commercialization, and globalism. While it seems so long ago, these traditions are not so different from traditions celebrated today. Many of the traditions held today by a majority of people have deep roots in the 19th and very early 20th Centuries. Did you find any similarities or differences from your own celebrations?

Thank you for visiting the virtual DCC Victorian Christmas exhibit! We hope to see you next year at the LSS Victorian Christmas event! Stay safe this holiday and in the coming New Year.

References and Disclaimer

References

A Victorian Christmas. “Yule Log.” http://www.avictorian.com/christmas_yulelog.html

Ancient History Encyclopedia. “Preparing the Yule Log.” https://www.ancient.eu/image/9617/preparing-the-yule-log/

BBC. “Victorian Christmas Activities: Holly Berries.” http://www.bbc.co.uk/victorianchristmas/activity/holly-berries.shtml

BBC. “Where Does Pantomime Really Come From.” https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/2JZ6TSqnd480n90dzN77r1Q/where-does-pantomime-really-come-from

Britannica. “A Visit from Saint Nicholas.” https://www.britannica.com/topic/A-Visit-from-St-Nicholas#:~:text=Nicholas%2C%20in%20full%20Account%20of,Sentinel%20on%20December%2023%2C%201823.

Britannica. “Christmas Tree.” https://www.britannica.com/plant/Christmas-tree#ref106886

Britannica. “Saint Nicholas Day.” https://www.britannica.com/topic/Saint-Nicholas-Day

Canadian Encyclopedia. “Boxing Day.” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/boxing-day

Castelow, Ellen. Historic UK. “Pantomime.” https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Pantomime/

Coca-Cola Australia. “The Definitive History of Santa Claus.” https://www.coca-colacompany.com/au/news/definitive-history-of-santa-claus

Cocoa and Heart. “Victorian Sweets.” https://www.cocoaandheart.co.uk/blog/read_178016/victorian-sweets.html

Copeman, Dawn. Time Travel Britain. “Who is Father Christmas?” https://www.timetravel-britain.com/articles/christmas/santa.shtml

Dodd, Sara M. "Conspicuous Consumption and Festive Follies: Victorian Images of Christmas." In Christmas, Ideology and Popular Culture, by Whiteley Sheila, 32-49. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008. Accessed December 8, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1r1xq8.7.

Dorling, Danny & Pattie, Charles & Pitts, Martin. "Christmas feasting and social class: Christmas feasting and everyday consumption." Food, Culture & Society 10, no. 3 (2007): 410. Gale General OneFile. https://link-gale-com.cyber.usask.ca/apps/doc/A174820138/ITOF?u=usaskmain&sid=ITOF&xid=ff93981f.

Durham University. “Victorian Durham.” https://community.dur.ac.uk/4schools.resources/victoriandurham/home6.html.

Flanders, Judith. The British Library. “Victorian Christmas” (2014). https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/victorian-christmas#

Goss, David W. “Christmas Past: A Victorian Garland.” Beaver 73, no. 6 (December 1993): 4. http://search.ebscohost.com.cyber.usask.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=31h&AN=9403290384&site=ehost-live.

Hadley, Lizzie M. "CHRISTMAS CUSTOMS." The Journal of Education 38, no. 24 (949) (1893): 395-96. http://www.jstor.com/stable/44038860.

Hendry, Hamish. Holidays and Happy Days, (London: Grant Richards, 1901; Project Gutenburg, 2011), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/37216/37216-h/37216-h.htm

Interpreter Guide for the Magic Schoolhouse Program

Interpreter Guide for the 2018 Victorian Christmas Program

Jane Austen Centre. “Snapdragon.” https://janeausten.co.uk/blogs/games-to-play/snapdragon

Klein, Christopher. History. “Why is the day after Christmas called Boxing Day?” https://www.history.com/news/why-is-the-day-after-christmas-called-boxing-day

Mimi Mathews. “A Victorian Ladies Christmas Gift Guide.” https://www.mimimatthews.com/2016/12/19/a-victorian-ladys-christmas-gift-guide/.

McKay, George. "Consumption, Coca-colonisation, Cultural Resistance – and Santa Claus." In Christmas, Ideology and Popular Culture, by Whiteley Sheila, 50-68. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008. Accessed December 8, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1r1xq8.8.

MET Museum. “Santa Claus in Camp by Thomas Nast” https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/427502?searchField=All&sortBy=Relevance&ft=thomas+nast&offset=0&rpp=20&pos=18

Moore, Clemment Clarke. A Visit From Saint Nick, 1823. https://books.google.ca/books?id=xEtMAQAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

"Outlines of Work for Each School Year." The Elementary School Teacher 5, no. 10 (1905): 614-615. http://www.jstor.com/stable/992445.

Powers, Ella Marie. "CHRISTMAS FOR THE LITTLE ONES." The Journal of Education 44, no. 22 (1896): 392. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44046941.

Raats, Hilary Naomi. "Visualizing the Victorian Christmas: Evolving Iconography and Symbolism in the Wake of Nineteenth-Century Commercialism." The General Brock University Undergraduate Journal of History 2 (2017): The General Brock University Undergraduate Journal of History, 04/17/2017, Vol.2, 49.

St. Nicholas Centre. “Saint Nicholas and the Origin of Santa Claus.” https://www.stnicholascenter.org/who-is-st-nicholas/origin-of-santa

Storey, John. “The Invention of the English Christmas” In Christmas, Ideology and Popular Culture, ed. By Sheila Whiteley. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008), 18. http://www.jstor.com/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1r1xq8.6.

Sullivan, Jill. The Politics of the Pantomime : Regional Identity in the Theatre 1860–1900. (Hertfordshire: University Of Hertfordshire Press, 2011.) Accessed July 14, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://search-proquest-com.cyber.usask.ca/legacydocview/EBC/716214?accountid=14739.

Tikkanen, Amy. Britannica. “Krampus.” https://www.britannica.com/topic/Krampus

Tille, Alexander. "German Christmas and the Christmas-Tree." Folklore 3, no. 2 (1892): 169. www.jstor.org/stable/1253194.

"Tradition of Helping; St. Stephen's Day." Chronicle - Herald, Dec 26, 2016. http://cyber.usask.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1855722023?accountid=14739.

Willis, Mathew. “What Santa Claus Really Looks Like” https://daily.jstor.org/what-santa-claus-looks-like/.

Why Christmas. “Christmas in the Netherlands.” https://www.whychristmas.com/cultures/holland.shtml

Why Christmas. “The Christmas Pickle.” https://www.whychristmas.com/customs/christmaspickle.shtml

Victorian and Albert Museum. “Victorian Christmas Traditions.” https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/victorian-christmas-traditions

Victoria and Albert Museum. “The First Christmas Card.” https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-first-christmas-card

Victoria and Albert Museum. “The Christmas Cracker.” https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-christmas-cracker

Victorianna. “Old Fashioned Victorian Christmas.” http://www.victoriana.com/christmas/default.htm