The Prospect of War

A Campus at War

When Canada went to war in 1914,

When Canada went to war in 1914,

its universities went with it.

The Great War profoundly altered the University of Saskatchewan and irrevocably transformed its sense of identity as an institution. 349 men and 1 woman from the University answered Britain’s call for volunteers.

As students and professors enlisted, the University population shrank — the entire College of Engineering closed. The women on campus “did their bit” by filling the positions vacated by the men.

Curriculum was affected as well. The prioritization of science and technology resulted in innovative discoveries, and the emergence of new disciplines.

Curriculum was affected as well. The prioritization of science and technology resulted in innovative discoveries, and the emergence of new disciplines.

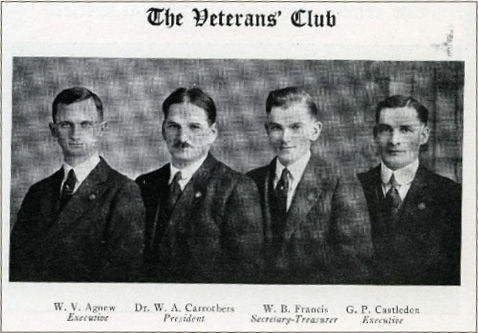

When peace came, efforts were made to reintegrate veterans, but the U of S struggled to assist the men who came back wounded in body and mind, and was ill-prepared to cope with the absence of those who never came home all.

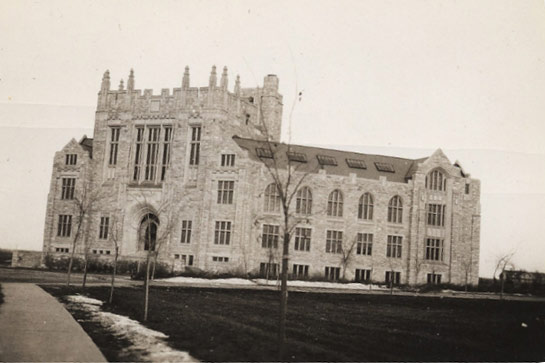

The University Created

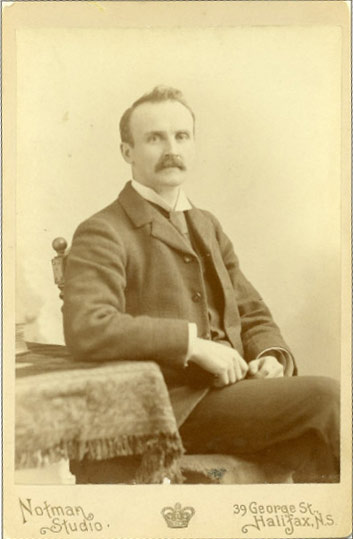

In 1907, the Scott Government passed “The University Act”, and the University of Saskatchewan was created in Saskatoon, with Walter Murray as its first President. Classes began in 1909 in the downtown Drinkle Building. The current campus started operations in 1912 and the first degrees were conferred the following year. By 1914, the University was growing rapidly — the student body had grown six fold since the institution’s opening in 1909.

When war was declared in 1914, many students, faculty, and staff, were eager to enlist. President Murray considered the War an opportunity to prove the University’s patriotism and fidelity to the British Empire. Enthusiasm for war reached every corner of campus, but few fully appreciated the horrors that were coming.

|

|

From Students to Soldiers

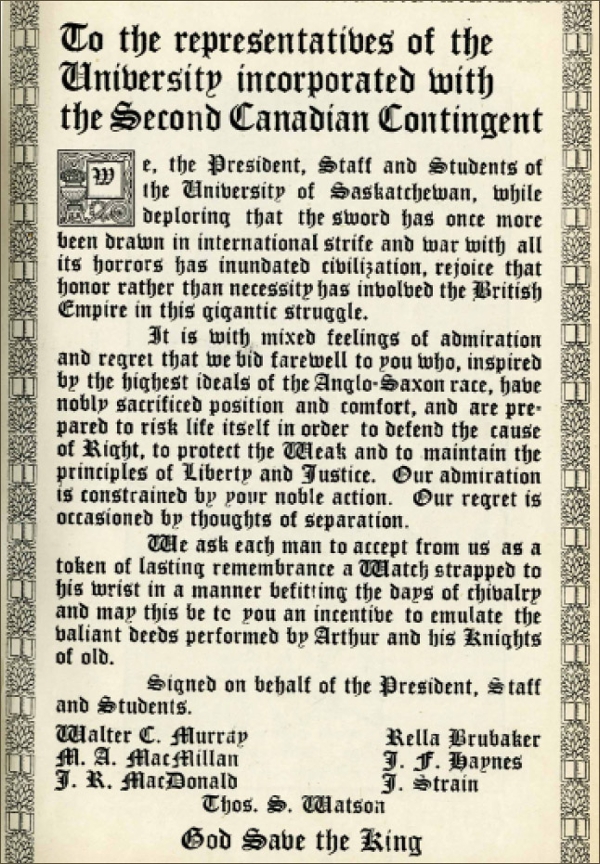

In October 1914, President Walter Murray gave a speech in which he described the War as “a fight for… the principles for which a university must stand.” Reflecting the sentiments of the time, he praised the students who enlisted as having been inspired by “the highest ideals of the Anglo-Saxon race.”

The University Governors offered inducements to secure volunteers: students who served would be granted one year’s academic credit, and staff would receive half-pay (more if they were married) and have their positions held until their return. One student who enlisted was John Diefenbaker, who would become Canada’s 13th Prime Minister. Diefenbaker received his Master of Arts degree in absentia.

|

|

|

"The Very Climax of Human Endeavour"

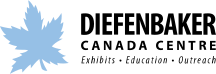

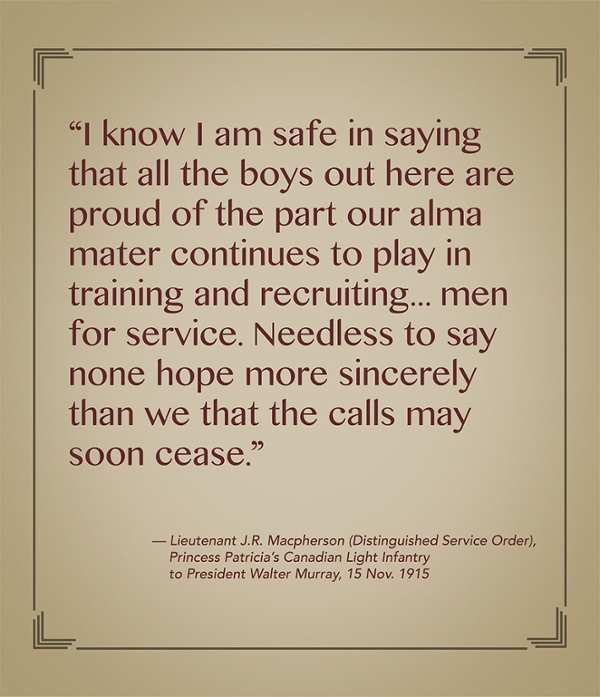

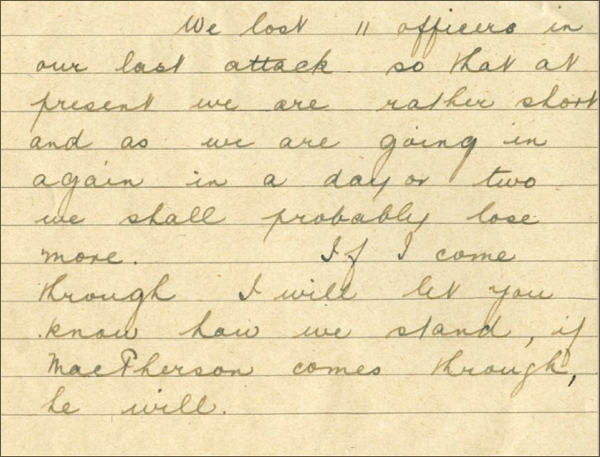

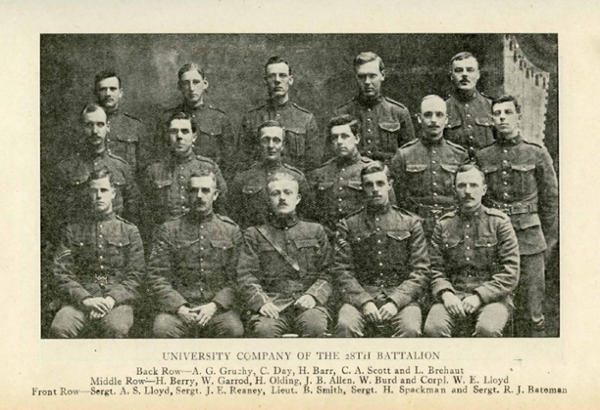

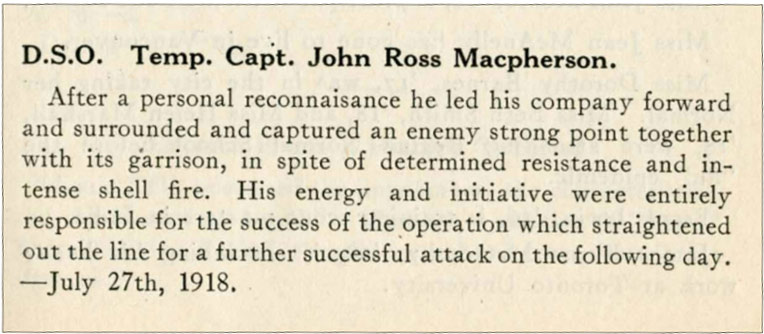

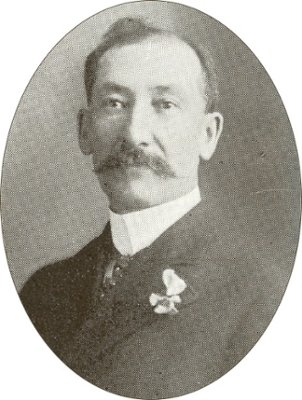

Reginald Bateman, a newly enlisted Professor of English, gave a recruitment speech in October 1914, in which he described war as “the very climax of human endeavour”— something that advanced civilizations, and tested a soldier’s manhood. Bateman was applauded, but some took exception. John Ross Macpherson, the editor of the University students’ newspaper, The Sheaf, criticized him for abandoning his students in a “Viking-like thirst for glory.”

Bateman served ably at the front and was moved away from the action when he was promoted to the rank of Major. True to his convictions however, he requested a demotion in order to return to the Front with the 46th Battalion. He was killed on September 3, 1918, when a shell struck his regimental headquarters.

|

|

|

Called to Serve

Selling the War

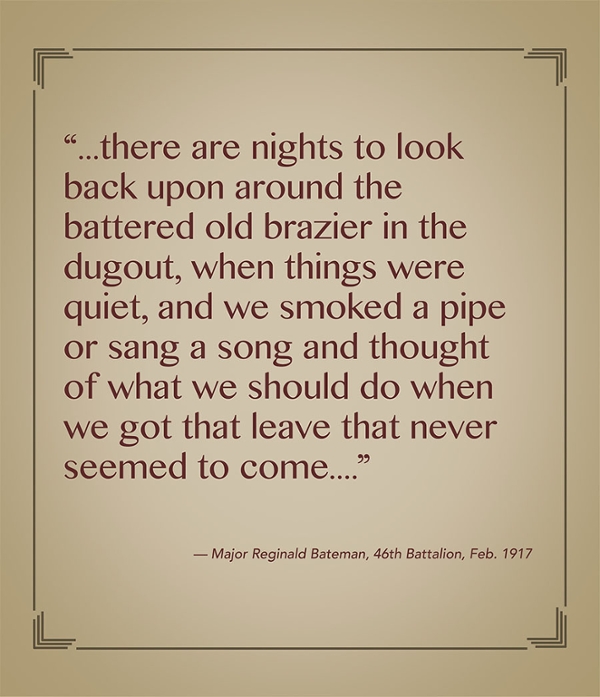

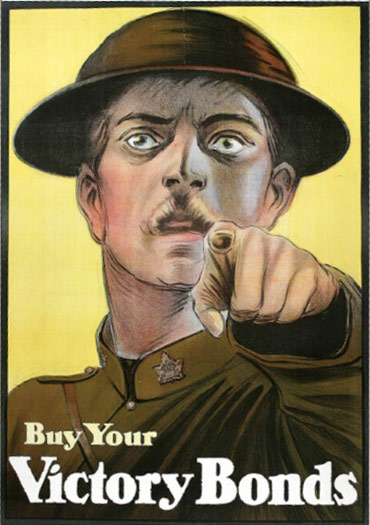

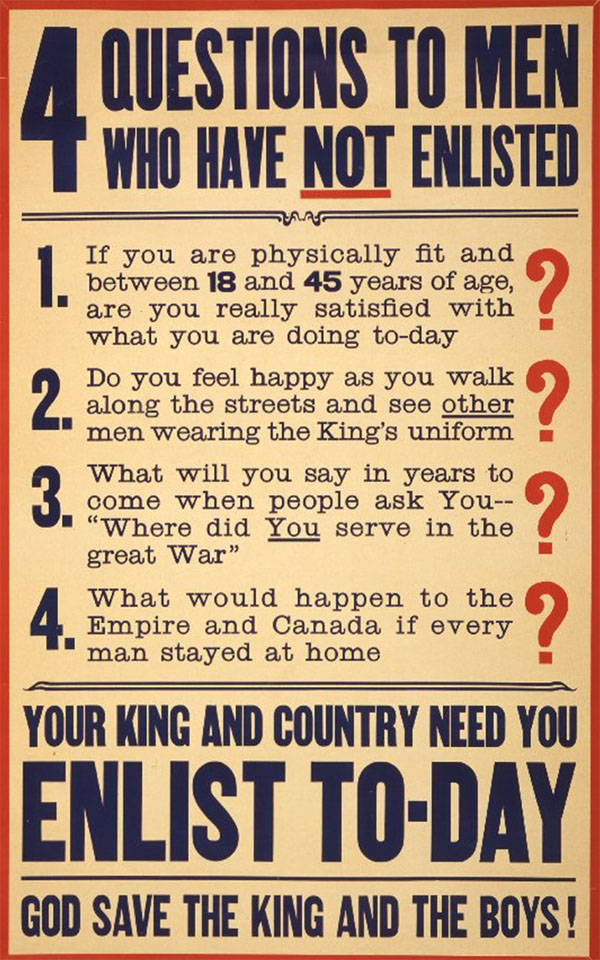

Propaganda targeted people’s emotions. If men could not be encouraged to enlist, they would be shamed into it. Civilians were pressured to buy Victory Bonds. The enemy was portrayed as vicious brutes willing to commit atrocities in their quest to destroy civilization.

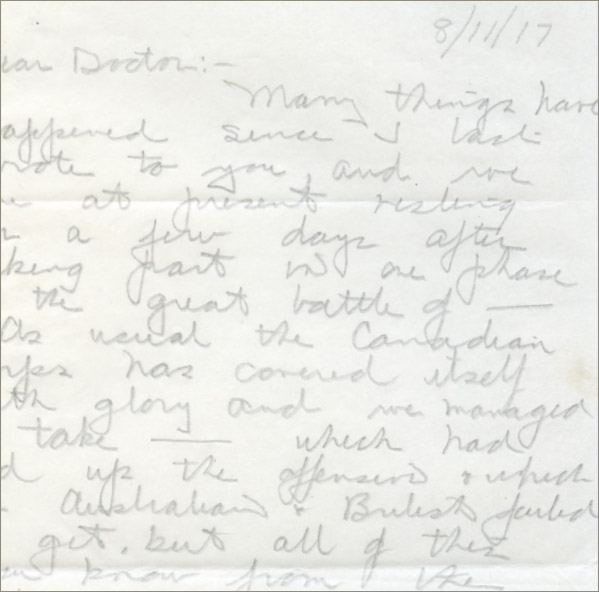

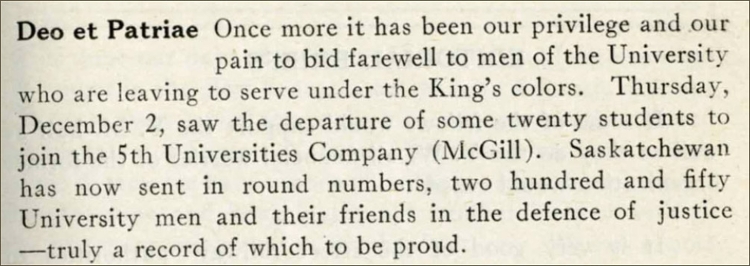

The Sheaf, the U of S newspaper, though decidedly patriotic, sometimes took a more balanced approach. The students who operated the newspaper tended to be more reflective in their editorials and became even more so as the War wore on.

Marching Together

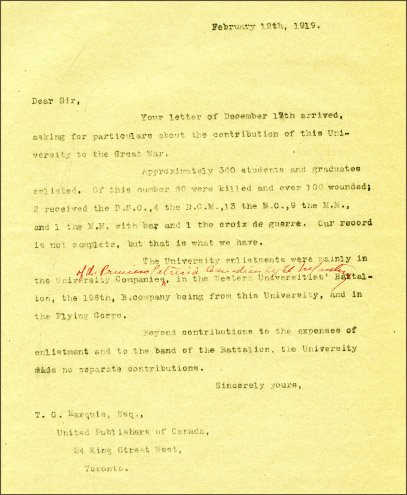

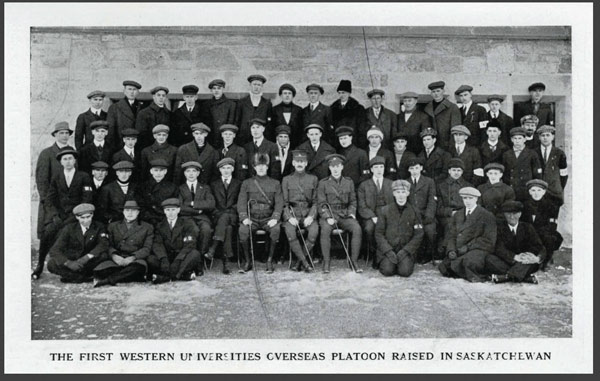

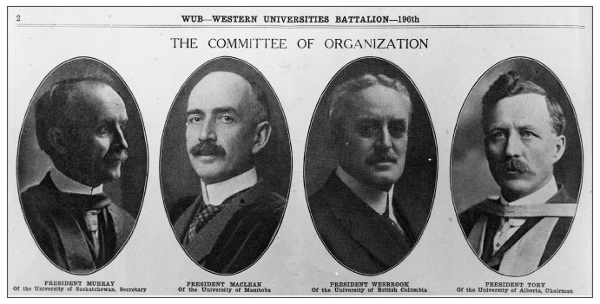

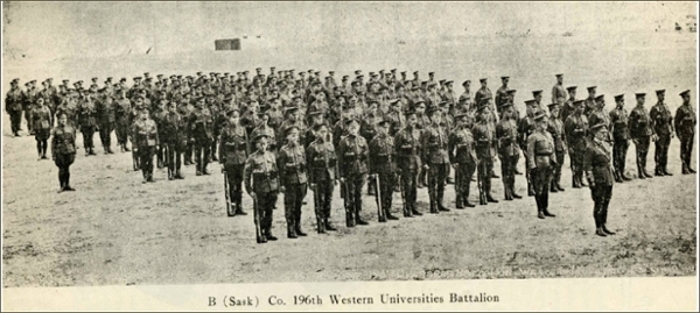

President Walter Murray believed men from the U of S should fight together, separate from companies formed from the general population. He led presidents from other western universities in lobbying for a battalion composed of faculty and students.

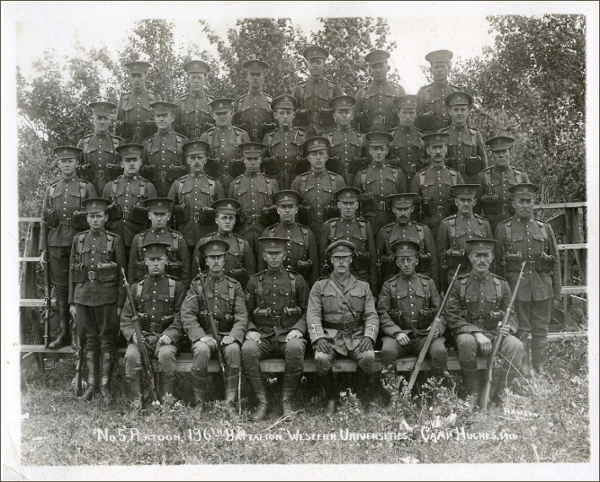

In February 1916, their efforts were rewarded. Recruits from the Universities of Saskatchewan, British Columbia, Alberta, and Manitoba amalgamated to form the 196th Western Universities Battalion.

|

|

“The Universities have become militant. Geologists are forming fours. Philosophers rush from muster parade to revolver practice. Professors of mathematics and English literature shout themselves hoarse at physical drill. Chemists are teaching bayonet practice and the mysteries of the Ross rifle…. We are citizens of a great Empire that has stood for self-government that is being tried by fire.” -Edmond Oliver

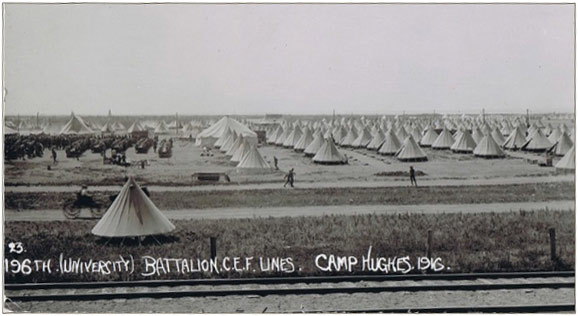

The 196th

The 196th Battalion went to Camp Hughes, Manitoba, for basic training, and from there to England in preparation for deployment to Europe.

However, the 196th was disbanded before it saw action — its members being divided amongst other units as reinforcements. Many U of S soldiers found themselves with other Saskatchewan men in the 46th South Saskatchewan Battalion.

The 46th fought in some of the worst battles, suffering especially high casualties, and earning the name “the Suicide Battalion.” Of the 5,374 men in the 46th Battalion, 4,917 were either killed or wounded.

A particularly costly battle was Passchendaele, where there were 403 casualties from the battalion’s strength of 600 men.

|

|

|

|

Students at Arms

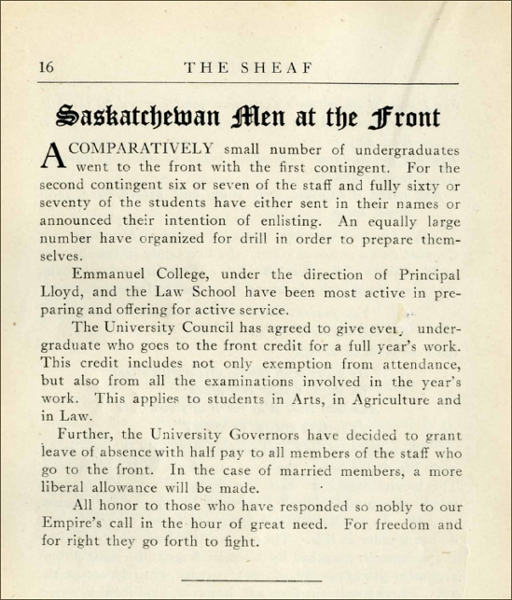

Students initially expressed great enthusiasm for the War and optimism over the British Empire’s chances for military success. Military drills were held on campus, and student enlistment was high — about half the male student population and most of the young faculty served voluntarily.

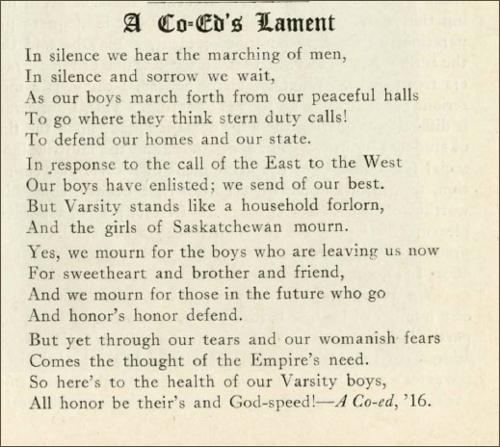

Many female students held in contempt those men who refused to volunteer.

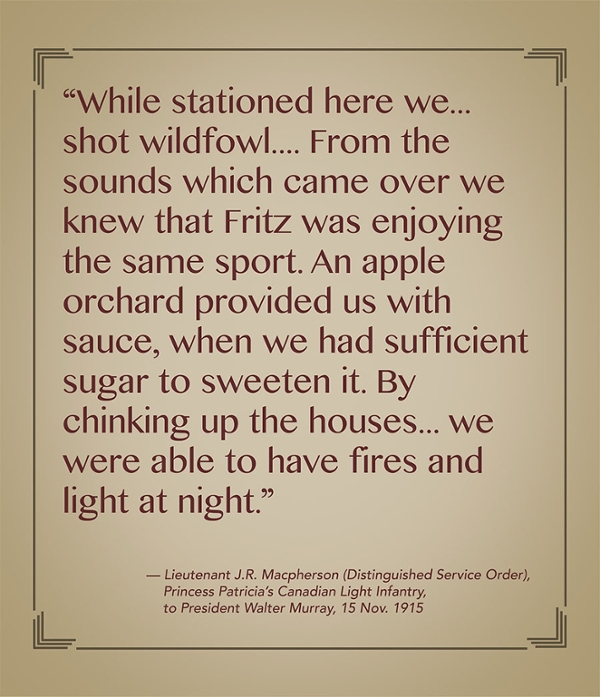

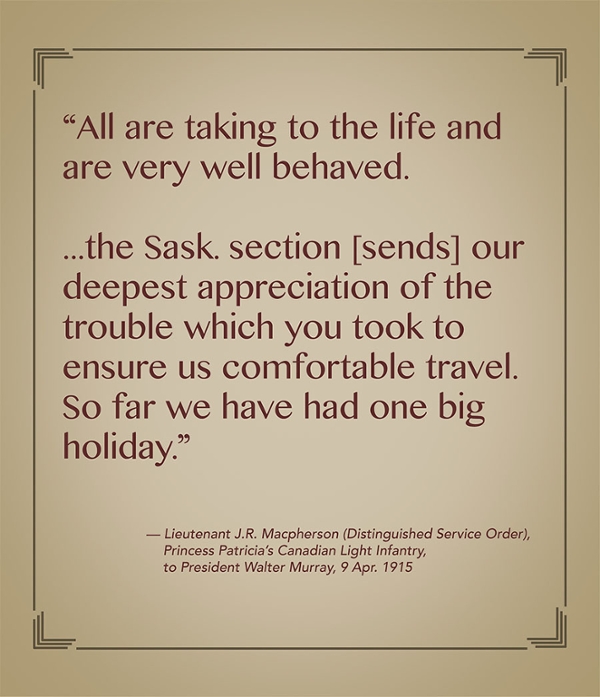

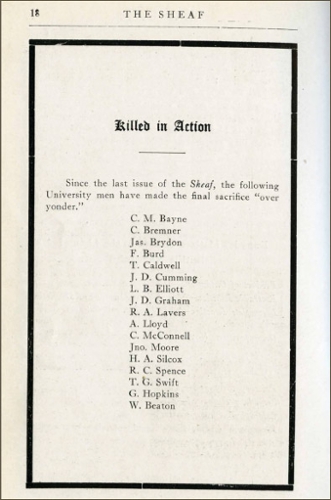

However, while some students openly criticized the faculty for deserting their classes, they were nonetheless ardent supporters of the War. John Ross Macpherson, for instance, editor of The Sheaf, and a student in the College of Arts, was one such voice. Macpherson served at the Front for three years before he was decorated with a Distinguished Service Order for his bravery — he was killed in action in August 1918.

“The war is still the subject uppermost in the minds of us all. As time goes on and we see many of our own boys departing on the service of their country we begin to realize a little more fully what it really means.” -The Sheaf, Nov. 1914

|

|

The Home Front

The Campus Soldiers On

The exodus of men joining the War changed the culture at the U of S. Membership in student organizations dropped steeply between 1914 and 1918. The Student Representative Council, which had relied on income from social events, was almost bankrupted. The Sheaf, likewise experienced financial trouble and nearly went out of print. The SRC and The Sheaf convinced President Murray to implement a compulsory student fee to support their continuation.

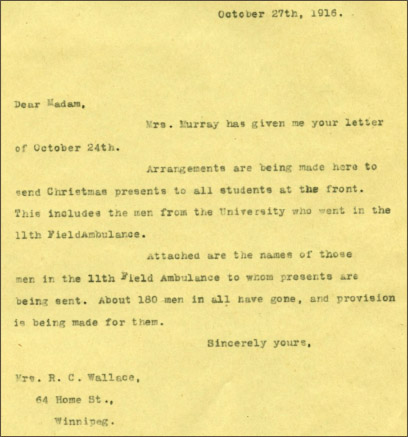

Throughout the War, students attempted to maintain aspects of earlier campus life. Though smaller than before, dances and parties continued to be held. The College of Agriculture’s Masquerade Balls were particularly popular. “Frosh Week” — a more rambunctious predecessor to today’s “Welcome Week” — also emerged during this time. Still, the War was ever-present on campus, from the articles in The Sheaf’s “Military Section,” to the activities of women in the University community led by Christina Murray, President Murray’s wife.

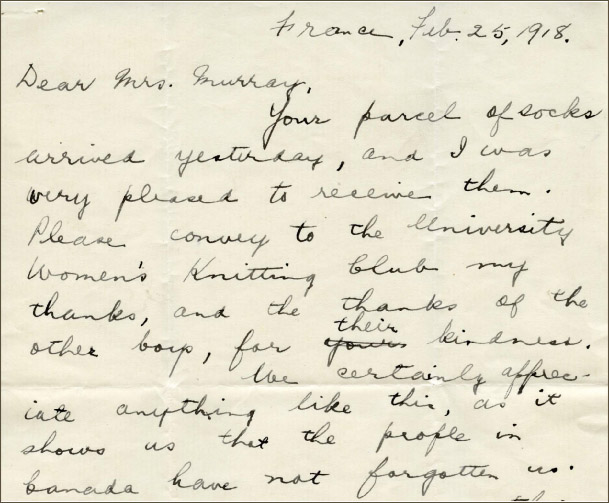

“My Dear Mrs. Murray,It must be a source of satisfaction to yourself and the untiring ladies’ association with you… to hear directly from men in France benefited by your efforts. …I would like adequately to voice the appreciation of as many men, each of whom is as much less apprehensive of the possibilities of tomorrow’s return to the trenches as the fortifying sense of a clean comfortable pair of socks can make…. Your comforts went to men of 10 Platoon, 3 Coy, Princess Patricia’s.” -Albert J. Weir, 13 Jul 1918

|

|

|

From Strife, Opportunities

Prior to the War, women were a minority on campus. When the male students began enlisting, women were presented with unique and unprecedented opportunities to study in new disciplines.

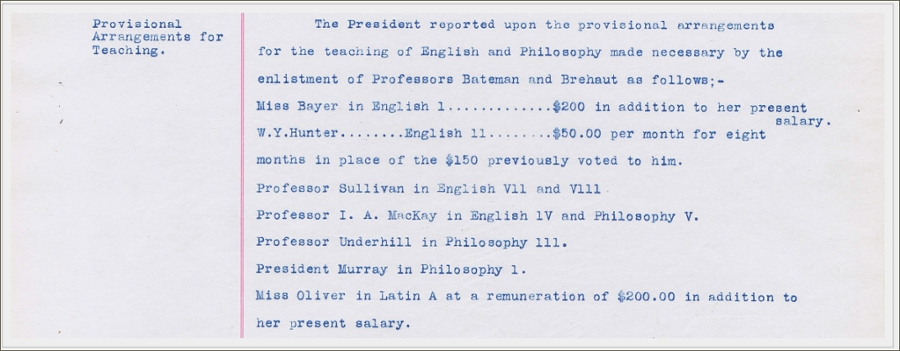

Staff and faculty composition changed as well. Pressed to replace male recruits, President Murray began hiring women in areas from which they had previously been absent.

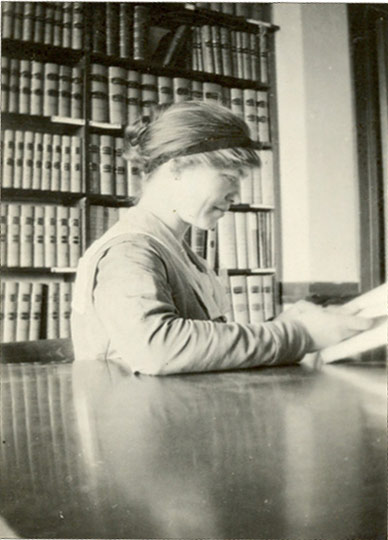

Professor Reginald Bateman was temporarily replaced by his fiancée Jean Bayer, who was Murray’s secretary and the University’s former librarian. Bayer was a popular instructor and joined the faculty permanently after Bateman was killed in 1918. She was appointed as an Assistant Professor in 1921. Female instructors became more common on campus, increasing from two in 1917 to fifteen in 1920.

|

|

|

Indigenous Representation on Campus

The Indigenous community on campus was small, but significant during the war years.

James McKay was a Métis lawyer appointed to the University’s first Board of Governors. As a Board member, he influenced wartime decisions at the U of S. According to The Sheaf, he “rarely missed a meeting… and no important decision was made without his cordial support.”

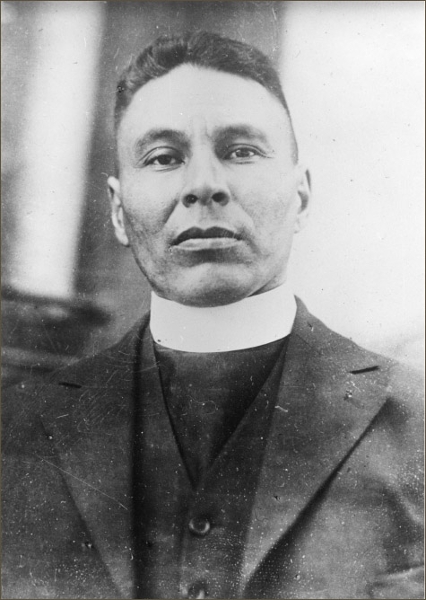

Edward Ahenakew was the University’s first Indigenous student and graduate. He attended Emmanuel College and was in the first graduating class in 1912.

Annie Maude (Nan) McKay served on the Student Representative Council. She was co-editor of The Sheaf during the War and became an Assistant Librarian after graduating in 1915. Nan was the first Indigenous woman to graduate from the U of S.

|

|

|

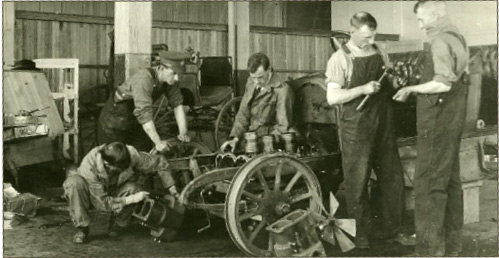

Winning the War Through Research

Whereas the teaching of humanities disciplines was the pre-war focus at the University, the Great War fueled a shift toward scientific research. Everyone believed that scientific breakthroughs were vital to winning the War, and to securing a future peace. As a founding member of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research of Canada (the precursor to the National Research Council), President Murray ensured that western universities received funding for innovative, nationally significant projects. The U of S has sustained its reputation in scientific research to this day.

One interesting project involved Chemistry Professor R.D MacLaurin and his engineering colleague A.R. Greig, who explored the conversion of straw into gaseous vapour to fuel engines. The project was ultimately abandoned because the process proved to be impractical.

|

|

|

Agricultural Advancements

John Bracken, a professor in the College of Agriculture initiated research into yield production and sustainability. His studies included finding crop varieties best suited to Saskatchewan’s climate.

Agricultural experimentation at the University also took on new meaning during the War. As the leading institution for agriculture in western Canada, the U of S assisted with meeting the demands for food production for the war effort.

In 1916, an outbreak of “wheat rust” devastated grain crops throughout the prairies. Walter P. Thompson, Professor and Head of the Biology Department, was tasked with finding a solution to prevent future plagues. A renowned geneticist, Thompson’s experimentation led to the development of rust resistant wheat hybrids.

|

|

Trials and Perseverance

As the War dragged on and casualty numbers grew, student opinions about the conflict became increasingly ambivalent. Some, who may have been partly motivated by a desire to avoid the aggressive recruitment campaigns at the University, returned to their family farms, choosing instead to help sustain crop production for the military.

One father wrote about his son to President Murray: “… he says he must either enlist or give up his studies and come home. He says the place has gone ‘crazy’ over enlisting and from all accounts I think he has used the right word.”

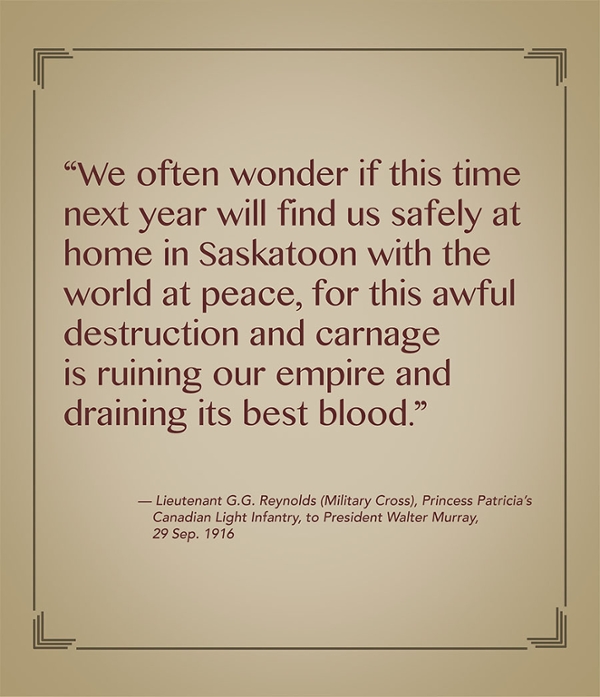

Towards the War’s end, students abandoned their romantic beliefs about the conflict, but they did not stop backing the war effort. The importance of supporting “the boys” overseas was never a subject open for debate.

Learning at the Front

The Battle of Vimy Ridge is considered as one of the defining moments in the formation of Canada’s identity. Victory came at a great cost, but also marked the first time that Canadian troops fought independently from the British forces.

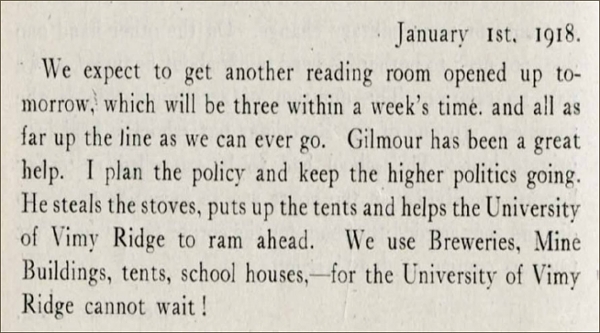

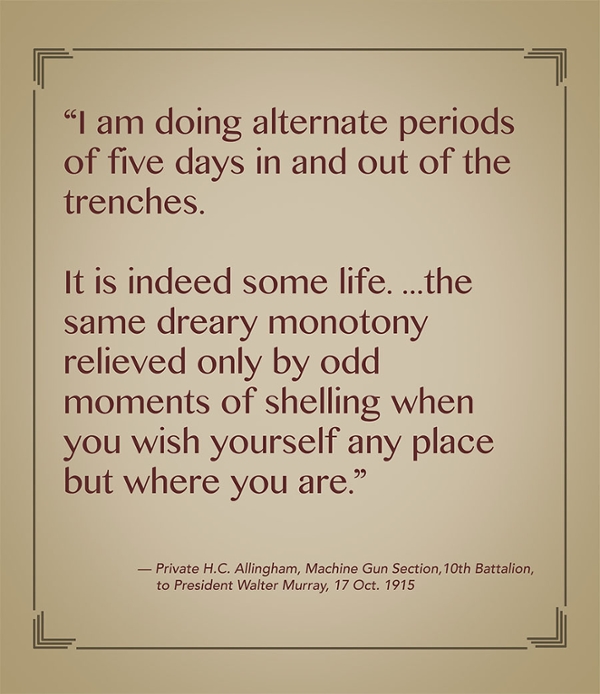

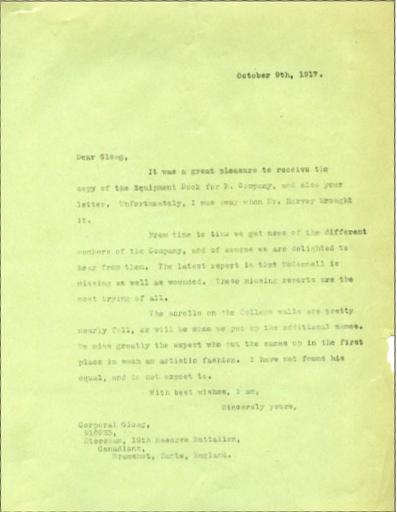

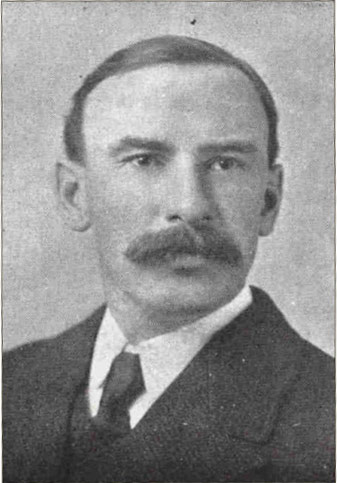

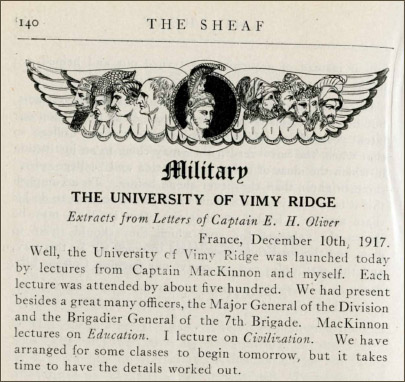

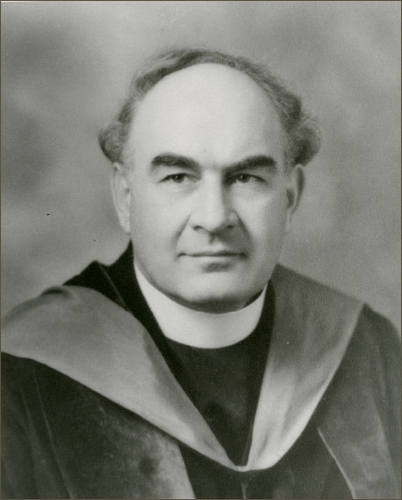

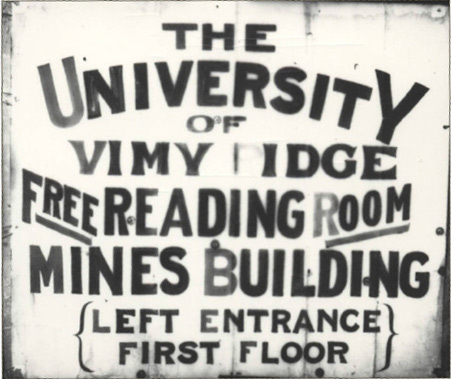

During the monotony between battles, men attempted to bring a sense of normalcy to their lives. Recognising this need, Cpt. Edmund Oliver the first history professor at the U of S, President of St. Andrew’s College, and Chaplain to the Western Universities Battalion, created the “University of Vimy Ridge” in December 1917.

The UVR’s purpose was to provide soldiers with knowledge and skills which would allow them to reintegrate into society. The UVR not only educated soldiers, but also brought a sense of hope for the future.

“The Vimy Ridge University scheme has many adjustments to make, but we men welcome the scheme and will take as much advantage as possible of its advantages. Dr. Oliver is working like a horse, he has the enthusiastic support of leading men in our Division, and I am sure he will make things go with a swing.” -Cpt G.G. Reynolds to Murray, 21 Jan 1918

|

|

|

|

Preparing the Boys for Peace

Rather than staying in one spot, the UVR followed the troops, staying just behind the Front. This created logistical challenges, including finding locations to conduct lectures, moving classes up and down the 30-mile front line, supplying materials, and finding instructors.

Rather than staying in one spot, the UVR followed the troops, staying just behind the Front. This created logistical challenges, including finding locations to conduct lectures, moving classes up and down the 30-mile front line, supplying materials, and finding instructors.

“The trouble is to chase around and discover a room, steal chairs, find lights, keep cheerful and deliver the goods. We have got results not because we are University people, but because we have walked our legs off and overcome every obstacle that has presented itself.” -Edmund Oliver

However, his efforts were rewarded. In February 1918, Oliver announced that nearly 4,000 soldiers had taken part in classes, over 6,000 had attended lectures, and over 4,000 books had been loaned in a single week.

The German offensive in March 1918 ended the UVR. However, the University of Vimy Ridge had given soldiers valuable skills and knowledge.

“Well, our reading room is so full that there are lots of boys standing up, and more are coming in through the door. I have just counted thirteen standing up because there is no room to sit down. ...Gilmour has gone out to steal some chairs.... Seven more boys have come in — twenty are standing up.... I glance up and there a fellow stands with a gasmask in his hand reading Tennyson...." -Edmund Oliver

Aftermath

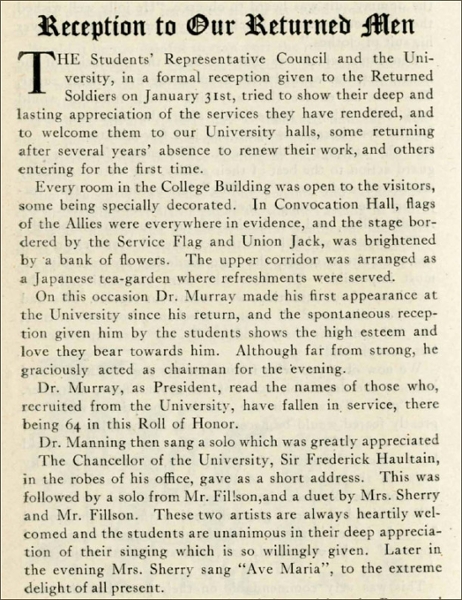

Homecoming

The end of the War brought students back to the U of S in unprecedented numbers. Veterans took advantage of the University’s vocational training programmes and offers of free tuition. As discharged soldiers flocked to campus, U of S resources became strained.

Walter Murray placed particular importance on occupational courses for disabled veterans. However, attitudes at the time focused energy on helping students with disabilities to learn to overcome physical obstacles and barriers rather than transforming the campus to make it more accessible for the disabled.

The Student Representative Council established the Comprehensive Accident and Sick Benefit Fund in 1926 — too late to help many student veterans.

|

|

|

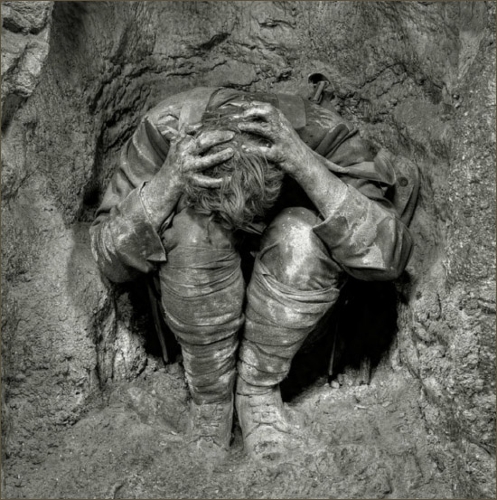

Broken Men

“…I believe I have become again quite normal mentally, which I was not when I first returned — I don’t think any man who has spent any length of time in the trenches can be….” -Reginald Bateman to Walter Murray, 5 Oct 1916

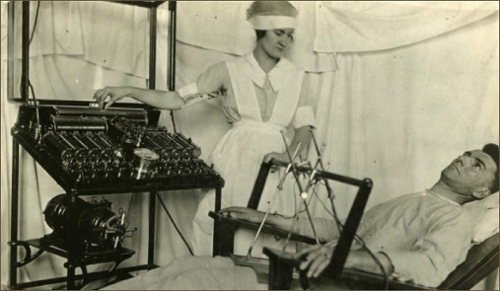

The violence and horrors of the trenches were overwhelming. Some men returned from the Front suffering from psychological afflictions which were more difficult to diagnose than physical wounds. Men became catatonic and mute, others babbled incoherently, while others still experienced spasms and could not stop crying.

Shell shock both incapacitated soldiers and carried great social stigma. Patients were often described as malingerers, cowards or emotionally weak. Treatments ranged from reprimands, to “analysis,” to hypnotism and electric shock therapy.

For an untold number of men, the symptoms of shell shock continued after the War, resulting in damaged familial relations, decreased employment opportunities, and a lasting sense of shame.

Today, physicians recognise these symptoms as evidence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“Fear is a terrible thing. It drives you into parts of your mind you don’t want to go to.“ -anonymous

|

|

|

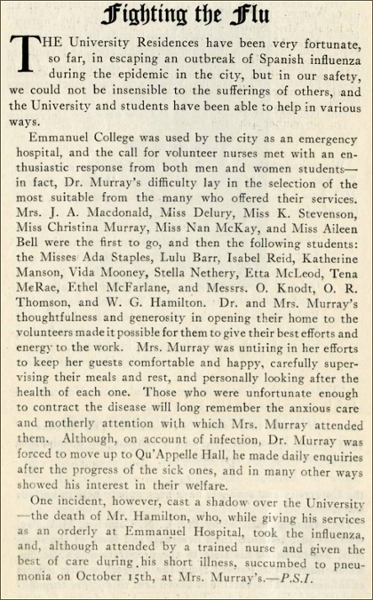

Fighting the Flu

In 1918, just as veterans were returning home and campus was coming to terms with the War, the U of S was struck again. In less than two years, the “Spanish influenza” killed 22 million people worldwide — more than the death toll of combat soldiers who had fought during the Great War.

At the University, 120 students, faculty and staff quarantined themselves, struggling to maintain campus life by continuing to hold classes. Emmanuel College was converted into the city hospital, and twenty faculty wives and female students volunteered as nurses; one of them contracted the illness and died. Of the 150 cases at the hospital, 6 died.

William Hamilton, who had volunteered as an orderly, was the University’s first recorded victim.

|

|

|

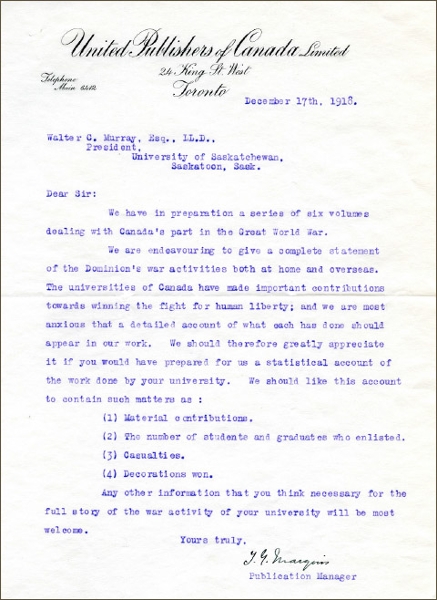

A Post-War Campus Remembers

In total, 350 students, faculty and staff enlisted during the Great War, 33 of whom were awarded medals of valour. Most students joined the infantry, though 40 became members of the Royal Flying Corps. One female student, Claire Rees, became a nurse. She is commemorated on a ribbon in the Peter Mackinnon Building as the only woman from the University who served overseas.

Of those who served, 28% were injured and 20% were killed — a mortality rate double that of the entire Canadian Expeditionary Forces.

“They are too near to be great, but our children shall understand when and how our fate was changed, and by whose hand” –dedication on the 46th Western Universities Battalion plaque

Today, evidence of the Great War’s impact can be seen throughout campus.

First painted in 1916, the Honour Roll terra cotta ribbons that line the halls in the Peter Mackinnon Building commemorate the students and faculty who fought in the War.

The Memorial Gates, which were constructed in 1927, marked the main entrance to campus. It memorialises members of the University community who were killed in the War. Remembrance Day services continue to be held there annually.

In 1933, a monument to the 46th Battalion was gifted to the University. It is located beside Nobel Plaza in the Bowl.

Perhaps the War’s greatest legacy though, are not physical things, but what make up the U of S today: excellence in research, advancements in technology, and strength in engagement and scholarship — the very identity of the University of Saskatchewan.

|

|