The Diefenbaker Canada Centre acknowledges that the Little Stone Schoolhouse resides on Treaty Six Territory and the Homeland of the Métis. The Centre pays its respect to the First Nation and Métis ancestors of this place and reaffirms its relationship with one another.

The Little Stone Schoolhouse online exhibit and physical location present a historical depiction of the education experience of settlers in Saskatchewan in the early 1900s. The Diefenbaker Canada Centre recognizes that the educational experiences of the estimated 150,000 Indigenous children through the residential school system were very different, with unfair and devastating results and long-term, intergenerational impacts. To learn more about the Residential School System, we encourage you to visit the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

Construction

Construction of the Original Victoria School

In 1887, the Saskatoon Board of Trustees began making plans to establish a permanent site for the construction of a school in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. These preliminary plans eventually led to the authorization of the School District to borrow $1,200 for the purpose of constructing a one-room schoolhouse that could accommodate 40 pupils on five lots of land.

In 1887, the Saskatoon Board of Trustees began making plans to establish a permanent site for the construction of a school in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. These preliminary plans eventually led to the authorization of the School District to borrow $1,200 for the purpose of constructing a one-room schoolhouse that could accommodate 40 pupils on five lots of land.

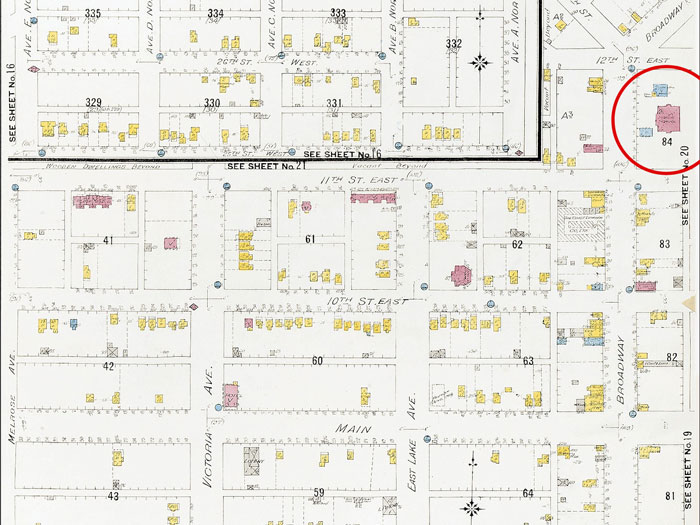

The Little Stone Schoolhouse, which was then known as the Victoria School, was constructed in 1887 on the southwest corner of Broadway and 12th Street in the neighborhood of Nutana. Because of its central location, it immediately became a gathering place for social, cultural, and religious community events in Saskatoon.

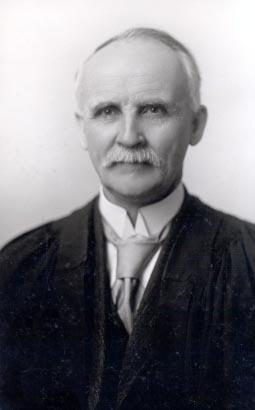

Alexander Marr, Stonemason

The original Victoria School was built by local stonemason Alexander Marr, known for owning the Marr Residence, which currently stands as the oldest residential building in Saskatoon. The original Victoria School features a single classroom, a pot-bellied stove to heat it, and a small cloakroom with a cupboard to hang jackets. There are two doors leading into the classroom, one for boys and one for girls, which was the typical practice at this time. Marr used a Prairie Vernacular design (characterized by its hip roof, robust mass, and strong form) that speaks to the importance of education to the community, as they poured resources into the quality of its architecture. Marr’s architectural designs continue to be admired in the Saskatoon community through both the Marr Residence and the Little Stone Schoolhouse.

The original Victoria School was built by local stonemason Alexander Marr, known for owning the Marr Residence, which currently stands as the oldest residential building in Saskatoon. The original Victoria School features a single classroom, a pot-bellied stove to heat it, and a small cloakroom with a cupboard to hang jackets. There are two doors leading into the classroom, one for boys and one for girls, which was the typical practice at this time. Marr used a Prairie Vernacular design (characterized by its hip roof, robust mass, and strong form) that speaks to the importance of education to the community, as they poured resources into the quality of its architecture. Marr’s architectural designs continue to be admired in the Saskatoon community through both the Marr Residence and the Little Stone Schoolhouse.

Many Saskatoon community members aided in the gathering of suitable granite stone for the school, which was found from the surrounding prairie landscape. Because lumber was rare and expensive to transport at this time, stone was a readily available and economical alternative.

The Expansion of the Saskatoon School System

The original Victoria School was a one-room schoolhouse that was used until a larger four-room brick veneer school was constructed in 1905, which was later demolished in 1911. When that four-room building was also outgrown, an even larger third Victoria School was constructed in 1909, consisting of an initial 8 rooms and two four-room additions. This third Victoria School was built for $44, 141 by the architect W.W. La Chance and was contracted by the Bigelow Brothers. The school is still in use today, with both English language and French Immersion programming, leading to its adoption of the bilingual name École Victoria School.

The original Victoria School was a one-room schoolhouse that was used until a larger four-room brick veneer school was constructed in 1905, which was later demolished in 1911. When that four-room building was also outgrown, an even larger third Victoria School was constructed in 1909, consisting of an initial 8 rooms and two four-room additions. This third Victoria School was built for $44, 141 by the architect W.W. La Chance and was contracted by the Bigelow Brothers. The school is still in use today, with both English language and French Immersion programming, leading to its adoption of the bilingual name École Victoria School.

|

|

|

Student Life

Life as a Student: Over 100 Years Ago

The lives of the children who attended the original Victoria School were drastically different than those of students who attend school in Saskatchewan today. Like almost all areas of the Canadian experience, the education system has evolved over the past 100 years and has welcomed new technologies, designs, and practices. The following are just some of the noteworthy examples of how prairie life, and the education system more specifically, has evolved since the late 1800’s and early 1900’s.

Transportation

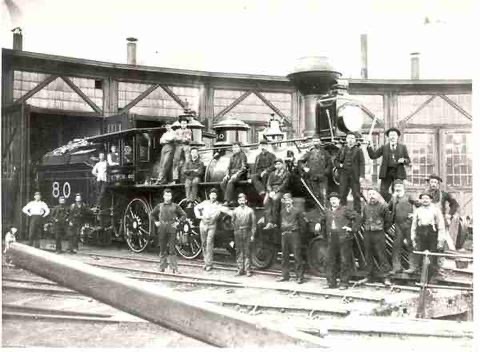

Transportation to and from school in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s typically involved walking, taking a horse and cart (in the summer), or taking a horse and sleigh (in the winter). The Saskatchewan River was difficult to navigate because of its shifting sandbars and shallowness. In 1890, the same year that the railway reached Saskatoon, the Long Lake, Qu’Appelle, and Saskatchewan Railway Company bridged the river at Saskatoon, making it possible for students who lived across the river to get an education at one of the three Victoria Schools. Although children could use this railway bridge to cross, it was generally not very safe or conducive to foot traffic. Thankfully, the Traffic Bridge was built in 1907 by the Saskatchewan Government for $106,000. This bridge was crucial in expanding the connections between Nutana and the west side communities of Saskatoon and Riversdale. Depending on the distance that a student lived from the school, children would often walk many kilometers to get their education each day.

Transportation to and from school in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s typically involved walking, taking a horse and cart (in the summer), or taking a horse and sleigh (in the winter). The Saskatchewan River was difficult to navigate because of its shifting sandbars and shallowness. In 1890, the same year that the railway reached Saskatoon, the Long Lake, Qu’Appelle, and Saskatchewan Railway Company bridged the river at Saskatoon, making it possible for students who lived across the river to get an education at one of the three Victoria Schools. Although children could use this railway bridge to cross, it was generally not very safe or conducive to foot traffic. Thankfully, the Traffic Bridge was built in 1907 by the Saskatchewan Government for $106,000. This bridge was crucial in expanding the connections between Nutana and the west side communities of Saskatoon and Riversdale. Depending on the distance that a student lived from the school, children would often walk many kilometers to get their education each day.

Grade Levels

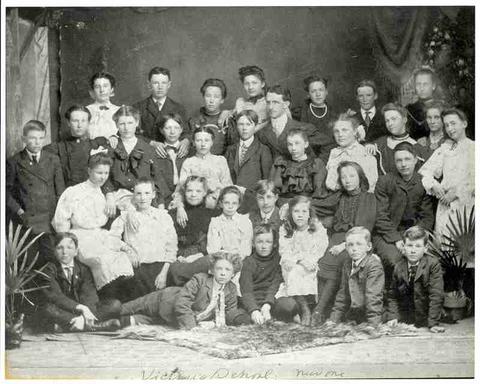

There was only one teacher for all of the students in the school, who varied in age from around five to fourteen (similar to children in K-8 today). At this time, however, instead of the grade system we use today, they used standards 1-3. This is why the desks in the original Victoria School are different in size, as the youngest students (in standard 1) sat in the smallest desks at the front and the oldest students (in standard 3) sat in the largest desks at the back. Although at one point there were 67 students registered at the original Victoria School, it was likely that not all students attended at the same time on the same days.

There was only one teacher for all of the students in the school, who varied in age from around five to fourteen (similar to children in K-8 today). At this time, however, instead of the grade system we use today, they used standards 1-3. This is why the desks in the original Victoria School are different in size, as the youngest students (in standard 1) sat in the smallest desks at the front and the oldest students (in standard 3) sat in the largest desks at the back. Although at one point there were 67 students registered at the original Victoria School, it was likely that not all students attended at the same time on the same days.

Teachers

James Leslie was the first teacher at the original Victoria School from 1888 to 1891, followed by George Horn from 1891 to 1898, and later Miss M.S. Ross, R.B. Irvine, and Gertrude Girvin in 1905.

The teachers at this time had many responsibilities outside their lessons. For example, teachers arrived early in the winter to start the fire in the stove, so that students would be warm once they arrived in the classroom. With about 40 children of various ages in the class at once, teachers had to be organized and stern. They had to make sure that each student was occupied and learning appropriate material for their age, make difficult decisions about whether to end class early due to approaching storms, and make sure that the fire was maintained throughout the entire day in the winter.

Most of the teachers in the early 20th century were women, who were drawn to the career because of its short training period and the opportunity to provide for their families. At this time, teaching children was seen as an extension of mothering, and female teachers were often paid half the salary of their male counterparts.

|

|

|

|

Discipline

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, teachers had to be very strict because of the large number of students, the wide range of children’s ages, the reality of having only one teacher in the classroom, and the social views and cultural practices of the time. With this in mind, the leather strap was one method for enforcing the rules of the classroom, as the student would hold their hands out with their palms up, and the teacher would strike the students’ hands with the leather. Corporal punishment was first prohibited in the classroom in British Columbia in 1973. The Saskatchewan Education Act was not officially amended to prohibit this use of discipline until 2005, although public perception had definitely shifted before that point.

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, teachers had to be very strict because of the large number of students, the wide range of children’s ages, the reality of having only one teacher in the classroom, and the social views and cultural practices of the time. With this in mind, the leather strap was one method for enforcing the rules of the classroom, as the student would hold their hands out with their palms up, and the teacher would strike the students’ hands with the leather. Corporal punishment was first prohibited in the classroom in British Columbia in 1973. The Saskatchewan Education Act was not officially amended to prohibit this use of discipline until 2005, although public perception had definitely shifted before that point.

The chair at the front of the classroom was another way to make sure that students followed the rules of the teacher. Misbehaving students would have to sit in front of their classmates for a specified time, similar to how some parents and teachers give ‘time-outs’ today. It was also common for teachers to draw a circle on the chalkboard and have misbehaving students hold their nose inside of it, a punishment that could range from five minutes to an hour.

At this time, writing with your left-hand was seen as unacceptable by many teachers. As punishment for this behaviour, the teacher would often tie the students’ left hand behind their back so that they were forced to write with their right hand. Although it is difficult to pin-point one singular cause for the negative associations that teachers had with left-handed students, this bias is apparent in many Western civilizations throughout history. There is, however, the possibility that teachers just wanted left-handed students to conform to the majority, making it easier for them in a predominantly right-handed society.

Health Inspections & Clothing

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, teachers would sometimes start the school day with a health inspection. Students would have to hold out their hands with their nails facing up, and the teacher would inspect each child’s hands to make sure they were cleaned properly. At this time, nail polish was not to be worn at school. If the students’ hands were not cleaned to the teacher’s standard, they would be told to go wash them and return to school the next day with clean hands, or they would be punished.

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, teachers would sometimes start the school day with a health inspection. Students would have to hold out their hands with their nails facing up, and the teacher would inspect each child’s hands to make sure they were cleaned properly. At this time, nail polish was not to be worn at school. If the students’ hands were not cleaned to the teacher’s standard, they would be told to go wash them and return to school the next day with clean hands, or they would be punished.

The clothing that students wore at this time was different than what students typically wear to school today. The girls would wear pinafores overtop their dresses, and the boys would wear suspenders or a vest.

Washrooms & Water

There were no washrooms or running water in the original Victoria School, so students relied on an outhouse and a well for their various needs. It was common for one student to go to the nearest well for a bucket of water, which would then be shared between all of the students in the classroom. They would have likely shared a ladle, typically referred to as a ‘dipper’, in order to drink the water out of the bucket.

|

|

Heat & Light

The original Victoria School was heated through a large pot-bellied iron stove that still stands in the centre of the room today. Wood logs were collected from nearby trees, and it was common for each student to bring a couple logs from home to supply the stove for the day. Lunch pails were placed beside the stove in the morning in order to warm food, because it would often freeze while students made their way to school in the winter.

Sunlight lit the original Victoria School through the three windows on either side of the building, but was often supplemented by kerosene lamps when it was necessary. Instead of a bulb, a kerosene lamp uses a flame to generate light, similar to a candle.

|

|

|

|

Slate Boards & Inkwells

Students at the original Victoria School used slates to complete most of their assignments and course work during the school day. Slates are essentially a tool used to draw and write, by using one rock to scratch the surface of another rock. Paper and fountain pens were available during the early 1900’s, but they were very expensive for everyday use, so slates were a more economical alternative. The slate boards were used to practice skills like spelling and math, while fountain pens and paper were used for larger assignments, like writing an essay.

Students at the original Victoria School used slates to complete most of their assignments and course work during the school day. Slates are essentially a tool used to draw and write, by using one rock to scratch the surface of another rock. Paper and fountain pens were available during the early 1900’s, but they were very expensive for everyday use, so slates were a more economical alternative. The slate boards were used to practice skills like spelling and math, while fountain pens and paper were used for larger assignments, like writing an essay.

The holes in the middle of some of the desks at the Little Stone Schoolhouse are called inkwells. These holes would have been filled with ink and then students would dip their fountain pens in the ink to write. Many of the girls wore their hair in braids at this time, and would get teased by having the ends of their hair dipped in the inkwells since the desks were so close together.

Pump Organ

The pump organ, which still currently resides in the Little Stone Schoolhouse, was made in 1883 in Detroit by a company named Farrand & Votey. It was sent by rail to Moose Jaw and was then brought to Saskatoon by oxen and cart, because the rail had not yet reached Saskatoon at that time. It would have likely taken two days to get the organ the 206 km from Moose Jaw to Saskatoon, a journey that would take about two and a half hours today.

To play a pump organ, one must press the pedal at the bottom of the organ, which forces air through the machine. Pressing on the keys, combined with this rush of air, creates sound and music can be played.

To play a pump organ, one must press the pedal at the bottom of the organ, which forces air through the machine. Pressing on the keys, combined with this rush of air, creates sound and music can be played.

|

|

The Hanging Globe & The Flag

The hanging globe and the flag are important artefacts in understanding the education priorities, both national and international, in the classroom at this time.

The hanging globe was used to accommodate for the height differences of the students at the original Victoria School. The teacher could easily raise or lower the globe depending on the height of the child that he or she was teaching. It was clearly a priority to educate students on international geography and the world outside of Saskatchewan.

The Union Jack was hung in the schoolhouse for two reasons. First, the iconic red and white, maple leaf flag that we have today was not designated as the Canadian national flag until 1965. The Union Jack was the official flag from 1867 to 1945. Second, since Canada became a country it had very close ties to Britain, with the Queen of England also reigning as the Queen of Canada.

|

|

The Move to the University of Saskatchewan

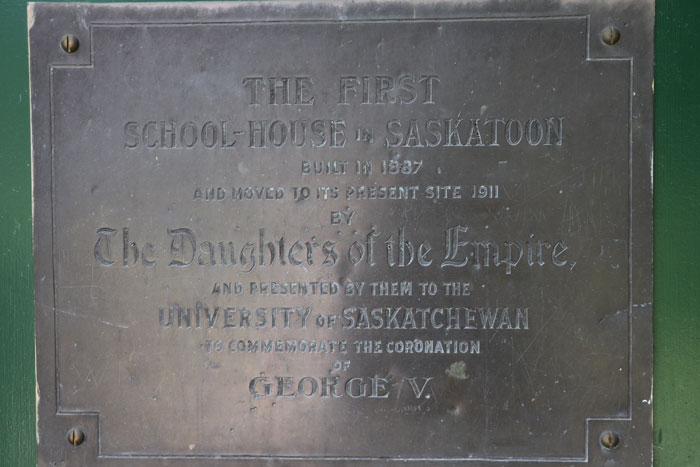

After the construction of the third Victoria School in 1909, when the original was no longer needed, W.P. Bate proposed that it be relocated to the University of Saskatchewan grounds. The local chapter of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire raised funds to preserve the school as a local heritage project, in recognition of the coronation of King George V.

The president of the University of Saskatchewan at this time, Walter Murray, agreed that the school should be relocated to campus and opened as a museum. The initiative of these Saskatoon community members to preserve the original Victoria School eventually secured its status as one of the first heritage conservation projects in western Canada. In 1911, the schoolhouse was dismantled, numbered stone by stone, and then rebuilt on its present day location under the direction of Saskatoon stonemason, Lorne Thompson. Once the relocation was complete, a plaque was hung on the door of the Little Stone Schoolhouse.

Once the relocation was complete, a plaque was hung on the door of the Little Stone Schoolhouse.

|

|

|

|

School House in Saskatoon

Built in 1887

And Moved to its Present Site, 1911

By

The Daughters of the Empire

And Presented by Them to the

University of Saskatchewan

To Commemorate the Coronation

of George V

1976 Re-Opening

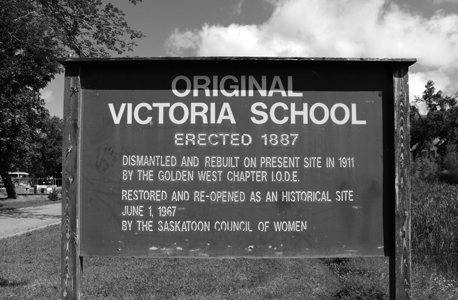

The Little Stone Schoolhouse was used for storage until 1965, when the Saskatoon Council of Women decided to refurbish the school as a centennial project, with Marjorie Clark as the first president of the Little Stone School Society.

The school reopened on June 1st, 1967, after recently being declared a Municipal Heritage Site by the Government of Saskatchewan under the Local Heritage Act (section 28). Staffed by volunteers, it was open to the public for tours through the late spring and summer. A sign was placed in front of the site at the Official Re-Opening in 1967.

|

|

|

Original Victoria School

Erected 1887

Dismantled and Rebuilt on Present Location

1911

By the Golden West Chapter I.O.D.E.

Restored and Re-Opened as an Historical Site

June 1, 1967

By the Saskatoon Council of Women

The Little Stone Schoolhouse Today

In 1981, the University of Saskatchewan assumed operations and management of the Little Stone Schoolhouse. The following year, in 1982, it was declared a Provincial Heritage Property. According to Canada Historic Places (which is a federal, provincial, and territorial collaboration to conserve historic buildings in Canada), the heritage value of the Little Stone Schoolhouse lies in the following three key areas:

- First, the elements that reflect its use as a school, such as its shape, the placement of its windows, and its central door.

- Second, the elements reflecting its stonemasonry, such as its form, walls, and steep hip roof.

- Finally, the elements reflecting its status as one of the first heritage conservation projects in Western Canada, such as its orientation on the lot and the materials used in the construction of its front door, windows, walls, and ceiling, which all help in dating the school’s reconstruction at the University of Saskatchewan campus.

|

|

Since then, it has continued to be a place of historical appreciation in the Saskatoon community and on the University of Saskatchewan campus. The main educational program at the Little Stone Schoolhouse features an introduction to the historical landmark, with the Historical Interpreter roleplaying as a schoolteacher with students from the early 1900’s. There are also complementary programs that offer immersive opportunities to participate in pioneer era games and explore artefacts. Additionally, annual public open houses allow everyone to enjoy what the Little Stone Schoolhouse has to offer.

Since then, it has continued to be a place of historical appreciation in the Saskatoon community and on the University of Saskatchewan campus. The main educational program at the Little Stone Schoolhouse features an introduction to the historical landmark, with the Historical Interpreter roleplaying as a schoolteacher with students from the early 1900’s. There are also complementary programs that offer immersive opportunities to participate in pioneer era games and explore artefacts. Additionally, annual public open houses allow everyone to enjoy what the Little Stone Schoolhouse has to offer.

If you’re looking for a child-friendly alternative for learning about the history of the Little Stone Schoolhouse, the Magic Schoolhouse Online Experience will be available soon on the Diefenbaker Canada Centre website. It features a historical introduction to the Little Stone Schoolhouse as well as fun activities and crafts that help children become immersed in the way of life of prairie settlers in the early 1900’s.

Acknowledgements

The “Little Stone Schoolhouse on the Prairie: The History of Saskatoon’s First Public Building” would not be complete without the help of many organizations around Saskatchewan. We would like to extend a sincere thank you to all those that contributed their resources and time in the development of the exhibit.

Thank you to the Saskatoon Public Library for their large collection of photographs and descriptions that document the history of the Little Stone Schoolhouse so well, and their generous contribution of allowing us to use some of their photographs in our exhibit.

Thank you to the City of Saskatoon Archives for generously offering the Municipal Heritage Advisory Committee (MHAC) Report and the fire insurance plans, as well as taking the time to go through their archive to provide any and all relevant information.

Thank you to the Saskatchewan Archival Information Network (SAIN) for their huge database that documents a wide range of the history of Saskatchewan. Many of the historic photos in the exhibit were found in their collections.

Finally, we would like to offer our thanks to all the individuals who contributed in their own way to the development of the exhibit. Your dedication and commitment did not go unnoticed.

Megan Ripplinger, exhibit curator

Megan Ripplinger was a summer student with the Diefenbaker Canada Centre from June to August 2020, working as a Heritage Interpreter. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Sociology, and she is beginning her Juris Doctor at the University of Saskatchewan, College of Law in the fall of 2020.

References

University of Saskatchewan Archives. Campus Buildings. “Victoria School House (Little Stone School House” http://scaa.usask.ca/gallery/uofs_buildings/home_victoria.htm

Canada’s Historic Places: A federal, provincial, and territorial collaboration. “Old Stone School” https://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=9207&pid=0

Saskatchewan Teacher’s Federation. “Saskatchewan Women in Education” https://www.stf.sk.ca/education-today/saskatchewan-women-education

Interpreter Guide for the Magic Schoolhouse Program

Saskatoon Public Library. Local History Collections Database. http://spldatabase.saskatoonlibrary.ca/ics-wpd/exec/icswppro.dll?AC=QBE_QUERY&TN=LHR_RAD&NP=4&QB0=AND&QF0=CLASSIFICATION&QI0==SCHOOLS+LITTLE+STONE+SCHOOL&QB1=OR&QF1=SUBJECT&QI1==LITTLE+STONE+SCHOOL&MR=20&RF=www_Canned%20Searches&QB2=AND&QF2=THUMBNAIL_IMAGE&QI2=*&QB3=NOT&QF3=ID_NUMBER&QI3=PH+95+78+73C

Victoria School, Municipal Heritage Advisory Committee report, ca. 1987, City of Saskatoon Archives

City of Saskatoon. Saskatoon History and Archives. https://www.saskatoon.ca/community-culture-heritage/saskatoon-history-archives/history

City of Saskatoon. “The History of our Bridges”https://www.saskatoon.ca/moving-around/bridges/history-our-bridges#:~:text=It%20is%20located%20on%20the%20site%20of%20Saskatoon%27s,of%20the%20line%20connecting%20Regina%20and%20Prince%20Albert.

Repeal 43 Committee. “School Corporal Punishment”. https://www.repeal43.org/school-corporal-punishment/#:~:text=2005%20Saskatchewan%20Education%20Act%202009%20Ontario%20Education%20Act,students%2C%20such%20punishment%20is%20now%20illegal%20throughout%20Canada.