Introduction

Sisters United

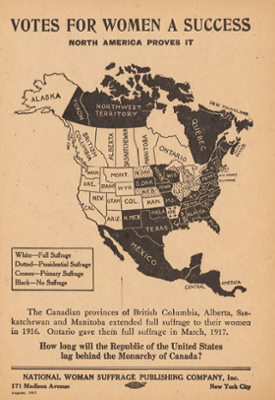

Different opinions and beliefs caused the struggle for women’s suffrage to take root differently in each of Canada’s provinces. As a result, political responses were varied. Sometimes, as with Québec and New Brunswick, there was much debate and opposition, while in Saskatchewan, there was much less government resistance.

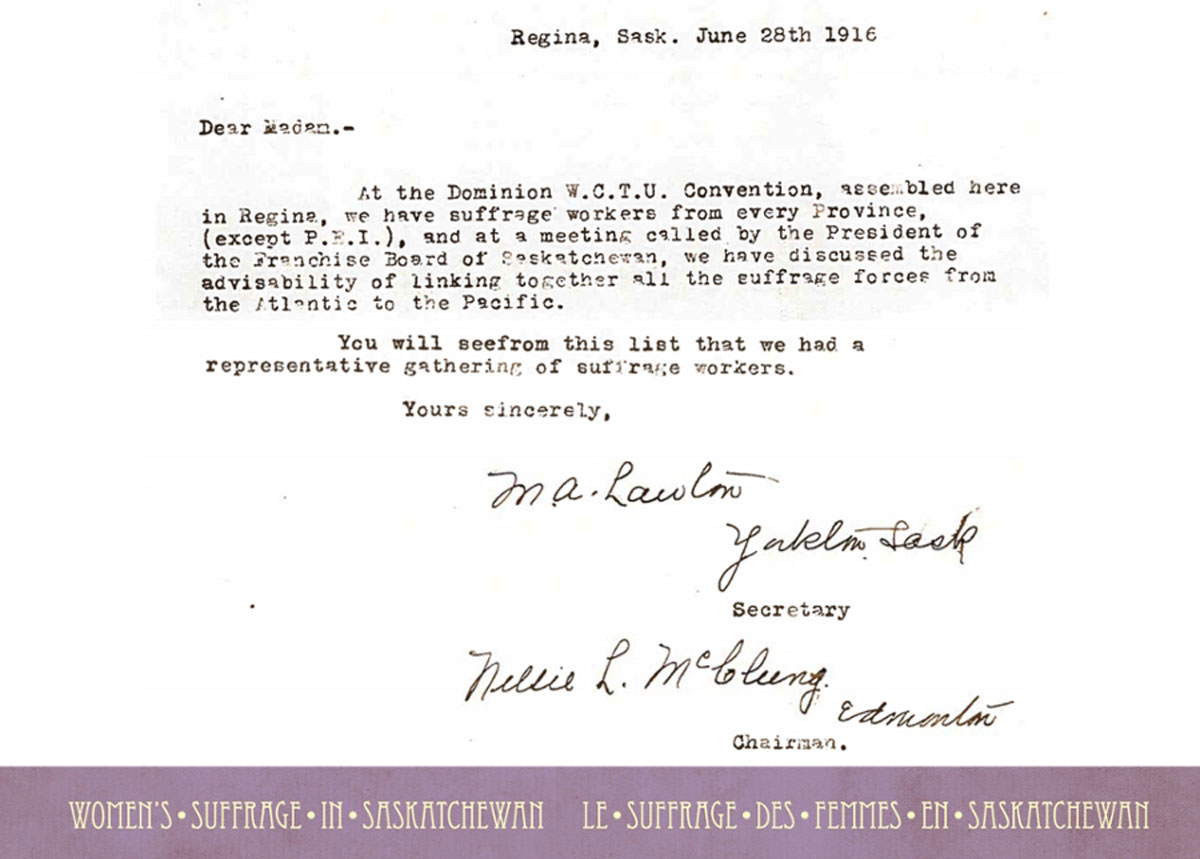

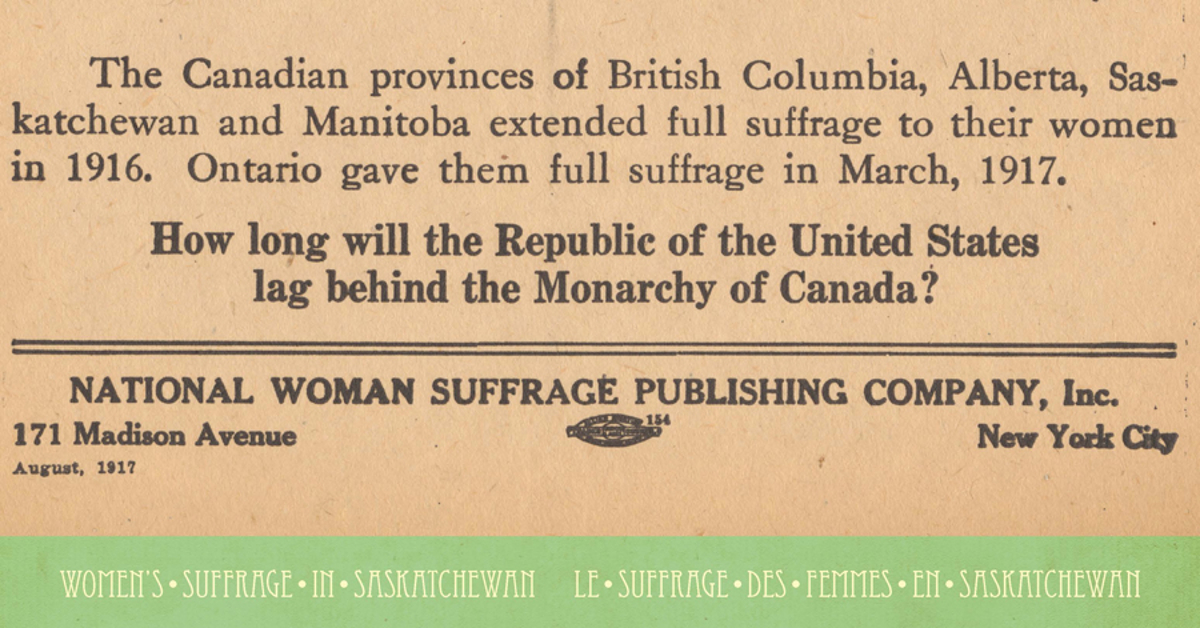

On the prairies, campaigns were co-ordinated by leaders from Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta. United, constant, lobbying from suffragists finally pressured these three provincial governments to grant women the franchise within three months of each other. 2016 marked the 100th anniversary of women winning the vote in Saskatchewan.

Other Canadian provinces followed suit. By 1920, seven out of ten provinces had extended suffrage to women.

Colours of the Movement

Suffragists used specific colours to identify themselves and symbolize the movement. British “suffragettes” wore purple, white, and green. In the U.S. many suffragists used gold and black, while others adapted the British colours to a green, white, and gold variant.

The movement was less publicly visible in Canada, and during our research with experts we were unable to find definite proof of what specific colours were used. However, both British and American activists, some of whom — like British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst — visited Canada regularly, would likely have provided inspiration.

In all probability, various colour schemes like those used in this exhibit would have made appearances in Canada.

A Common Goal

The Canadian women’s suffrage movement began in earnest in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Motivated by the larger British and American movements, supporters of Canadian suffrage, called “suffragists,” campaigned on a number of issues, including prohibition, gender equality, property rights, safe working conditions, medical care and social justice.

Suffragists in Canada, Britain and the U.S. shared the common goal of wanting women to attain the vote, but the approaches taken in each country were distinct.

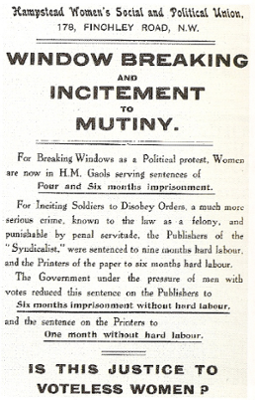

Deeds, Not Words

Suffragists in Britain initially agitated for the franchise peaceably. However, failing significant Parliamentary action, some women, led by activist Emmeline Pankhurst, formed a breakaway faction — the Women’s Social and Political Union. Calling themselves “suffragettes” to distance themselves from their suffragist sisters, they adopted militant tactics. They destroyed, burned and bombed property, initiated riots, chained themselves to structures, and tried to force their way into the House of Commons. The British government retaliated with brutal force, beating and arresting protesters, and force-feeding those who went on hunger strikes.

Suffragists in Britain initially agitated for the franchise peaceably. However, failing significant Parliamentary action, some women, led by activist Emmeline Pankhurst, formed a breakaway faction — the Women’s Social and Political Union. Calling themselves “suffragettes” to distance themselves from their suffragist sisters, they adopted militant tactics. They destroyed, burned and bombed property, initiated riots, chained themselves to structures, and tried to force their way into the House of Commons. The British government retaliated with brutal force, beating and arresting protesters, and force-feeding those who went on hunger strikes.

Inspired by their suffragette sisters across the Atlantic, more radical Americans formed their own organization: the National Women’s Party. Though not as belligerent as their British counterparts, National Women’s Party members held their own public demonstrations, sit-ins, and hunger strikes.

Sisters in the Cause

Though tamer, the Canadian drive for suffrage was just as determined, and support for the cause spread quickly.

Though tamer, the Canadian drive for suffrage was just as determined, and support for the cause spread quickly.

In Saskatchewan, a province heavily dependent on agriculture, co-operative organisations provided women significant opportunities to engage in agrarian politics. Rural farmwomen also provided essential leadership and joined with urban organizations. Together, these “sisters in the cause” united and became powerful advocates for provincial suffrage.

Violet McNaughton was especially important within the Saskatchewan movement. As a director in both the co-operative and suffrage movements, McNaughton was instrumental in bringing together women throughout the province. With other suffragist leaders, she raised public awareness and support by collecting petitions, giving lectures, and organizing rallies and other public events. McNaughton’s persistence was critical in helping Saskatchewan women win the vote.

Knowledge is Power

Education played a major role in the suffragist movement. Until the 1900s, formal schooling beyond elementary school was limited for women, especially in rural Saskatchewan. The remoteness of farms and the demands of seasonal labour made attending school difficult. By the early part of the century, however, one-room schoolhouses were becoming common. Still, the usual expectation was that girls would become wives and homemakers, so education seemed less important for them than for boys.

Education played a major role in the suffragist movement. Until the 1900s, formal schooling beyond elementary school was limited for women, especially in rural Saskatchewan. The remoteness of farms and the demands of seasonal labour made attending school difficult. By the early part of the century, however, one-room schoolhouses were becoming common. Still, the usual expectation was that girls would become wives and homemakers, so education seemed less important for them than for boys.

In urban communities, private tutors were available from the mid-1800s for the middle and upper classes. Colleges or universities were also accessible and fairly progressive. At the University of Saskatchewan, for example, sexual equality was written directly into the University Act of 1907.

Into a Man's World

Though women began taking advantage of educational opportunities, they were discouraged from pursuing professional careers. Most of them enrolled in liberal arts classes, completing degrees related to home economics.

Though women began taking advantage of educational opportunities, they were discouraged from pursuing professional careers. Most of them enrolled in liberal arts classes, completing degrees related to home economics.

Regardless, higher education provided women with chances to explore political theories and interact with like-minded women. They began to question long-established gender roles. Graduates formed alumni societies, where discussions about social issues, such as suffrage, took place.

A few women ventured into male-dominated disciplines such as medicine. Elizabeth Scott Matheson was one of these women. Securing a degree from the Women’s Medical College in Kingston, she practiced in Onion Lake, Saskatchewan. The Department of Indian Affairs appointed her as the Government Doctor for the Indigenous peoples of the area.

Inspiring Women

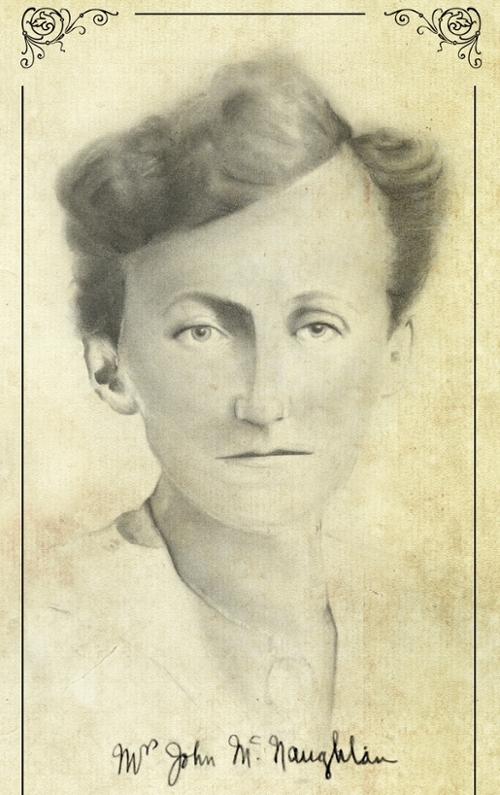

Violet McNaughton

Violet McNaughton remains the best-known advocate for women’s suffrage in Saskatchewan. Also a defender of the co-operative and agrarian movements in the province, she worked closely with leaders in Alberta and Manitoba to advance rural reform.

Violet McNaughton remains the best-known advocate for women’s suffrage in Saskatchewan. Also a defender of the co-operative and agrarian movements in the province, she worked closely with leaders in Alberta and Manitoba to advance rural reform.

Originally from Kent, England, Violet was introduced to the co-operative and suffrage movements there. She brought this knowledge with her when she immigrated to Harris. She married John McNaughton, who became her most loyal partner and supporter. As an agrarian feminist, Violet spearheaded many social reform strategies. These resulted in successes such as equal franchise, the recruiting of doctors, nurses and midwives for rural communities, the establishment of hospitals, libraries and schools, and improvements to the agrarian system.

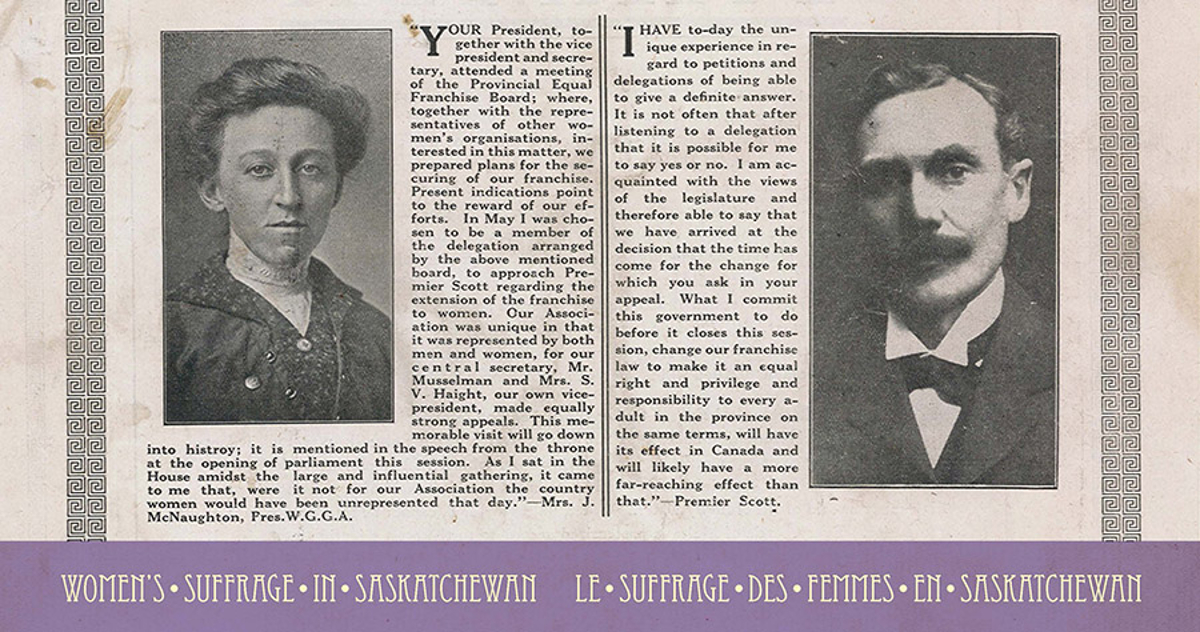

Violet McNaughton became the first woman to sit on the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association Board of Directors. In 1914, she established the Women Grain Growers’ Association, becoming its first President. Violet’s executive included Zoa Haight, who was Vice President, and Erma Stocking as Secretary-Treasurer.

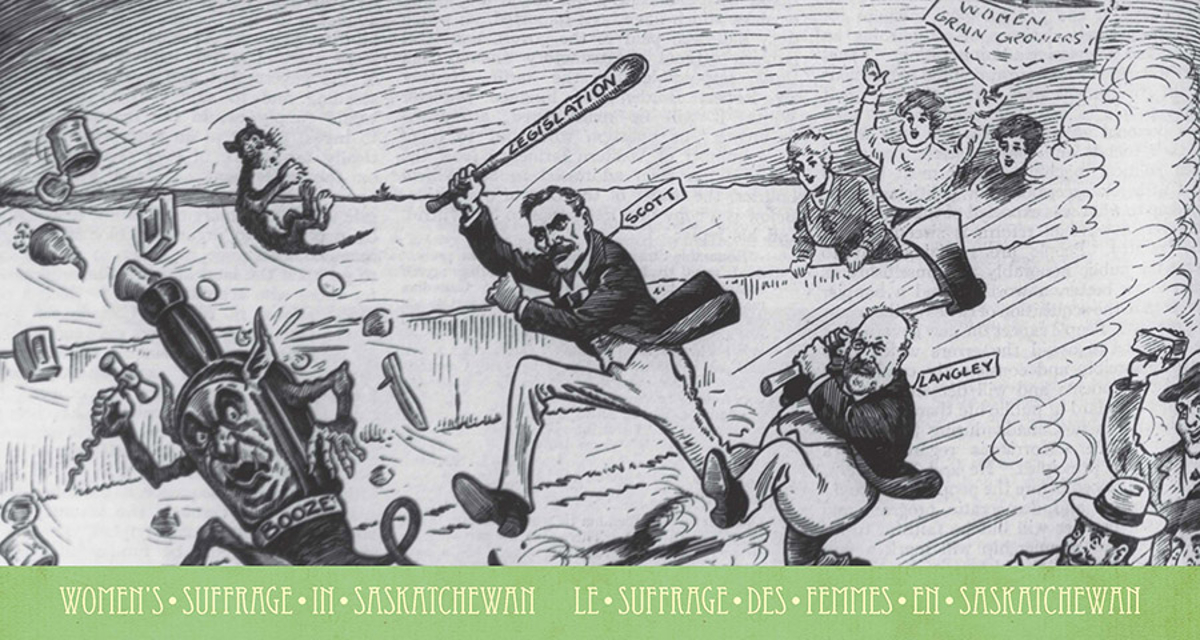

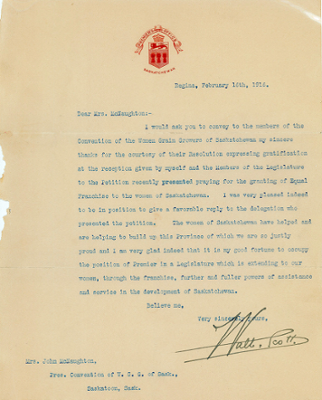

In 1915, Violet created the Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board by uniting three organizations: the Women Grain Growers’ Association, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Political Equity League. Although these organizations represented very different urban and rural philosophies, they all believed in equal franchise. The Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board achieved this objective in Regina on March 1916, when Premier Walter Scott awarded the vote to Saskatchewan women.

Click here to listen to an interview with Violet McNaughton about the suffrage movement in Saskatchewan.

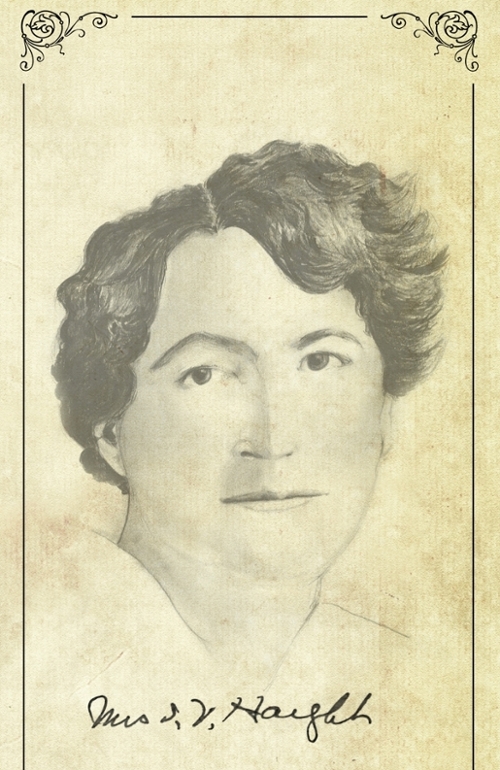

Zoa Haight

As the Women Grain Growers’ Association’s Vice President, Zoa Haight served alongside Violet McNaughton, who was President.

As the Women Grain Growers’ Association’s Vice President, Zoa Haight served alongside Violet McNaughton, who was President.

Zoa’s strong will and enthusiasm stood in contrast to Violet’s quiet demeanor, but the women developed a strong political partnership. Together, they helped to shape the provincial laws that bettered rural life for all.

Zoa was also the Vice President of the Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board, which Violet founded.

An active participant in mainstream politics, she ran for provincial office as a member of the Non-Partisan League in the district of Thunder Creek, in 1917. She was not, however, successful in winning her seat.

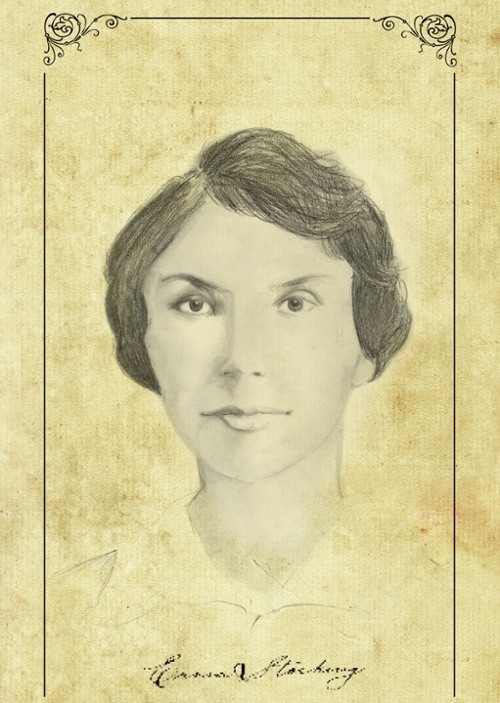

Erma Stocking

Erma Stocking served as the Secretary-Treasurer of the Women Grain Growers’ Association until 1917. She was also the President of the Woodlawn chapter of the Women Grain Growers’ Association.

Erma Stocking served as the Secretary-Treasurer of the Women Grain Growers’ Association until 1917. She was also the President of the Woodlawn chapter of the Women Grain Growers’ Association.

As Secretary-Treasurer, Erma was responsible for publishing Women Grain Growers’ Association news in the women’s section of the Saskatchewan Grain Grower’s Association newspaper. Her columns included letters and submissions from farm women on subjects related to parenting, domestic practices, relief work and suffrage.

Erma was a strong supporter of the creation of rural libraries and believed that giving women access to literature helped to educate them and enrich their lives.

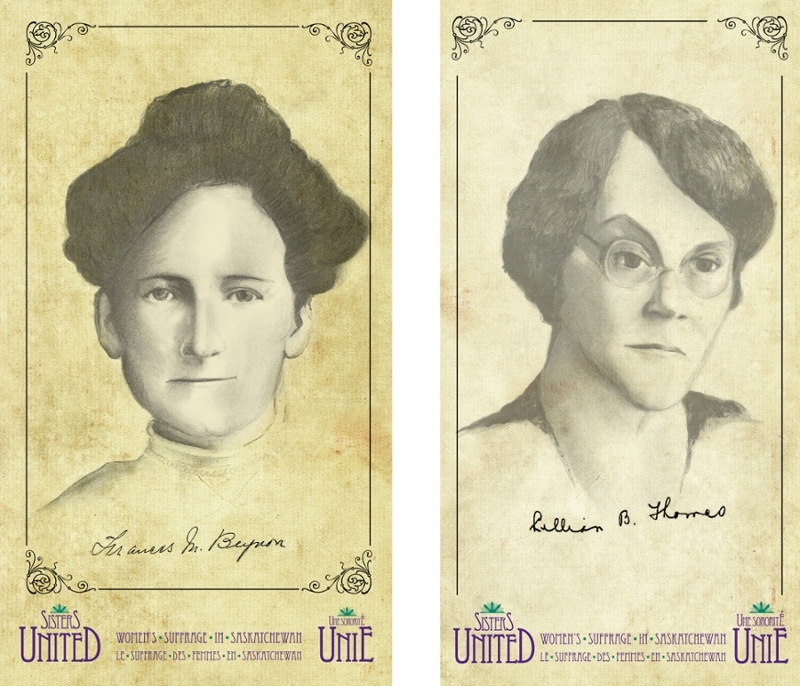

The Beynon Sisters

Francis Marion Beynon was the editor of the women’s section of the Grain Growers’ Guide from 1912 to 1917 — the first woman to hold this position. Her sister, Lillian Beynon Thomas, was the assistant editor of the Winnipeg Weekly Free Press, and published a popular women’s column.Journalism was another important tool used by Western Canadian suffragists to promote equal franchise across the prairies. The Beynon sisters of Winnipeg, whom Violet McNaughton considered her mentors, were both journalists and were heavily involved in the cause.

Francis Marion Beynon was the editor of the women’s section of the Grain Growers’ Guide from 1912 to 1917 — the first woman to hold this position. Her sister, Lillian Beynon Thomas, was the assistant editor of the Winnipeg Weekly Free Press, and published a popular women’s column.Journalism was another important tool used by Western Canadian suffragists to promote equal franchise across the prairies. The Beynon sisters of Winnipeg, whom Violet McNaughton considered her mentors, were both journalists and were heavily involved in the cause.

Both Francis and Lillian were outspoken pacifists and strongly supported the rights of minorities and the disadvantaged.

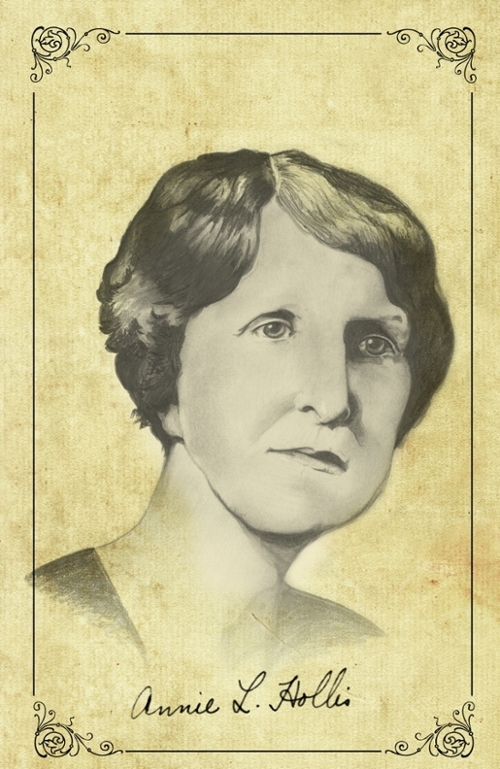

Annie Hollis

Annie immigrated to Shaunavon, Saskatchewan, from Portsmouth, England in 1914.

Annie immigrated to Shaunavon, Saskatchewan, from Portsmouth, England in 1914.

Although it was unconventional at that time, Annie continued teaching after her marriage. Passionate about education, she helped to establish a school for the deaf in Saskatoon.

Annie joined the generations of women who furthered the Women Grain Growers’ Association’s philosophies.

Elected to the association’s executive in 1917, she continued advocating for women’s issues, even after the provincial vote had been secured.

Alice Lawton

The Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board was led by Alice Lawton, who was its first President.

The Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board brought together members of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Women Grain Growers’ Association and the Political Equity League.

In February of 1916, Alice led the delegation that secured women the vote from Saskatchewan’s Premier Walter Scott.

For or Against

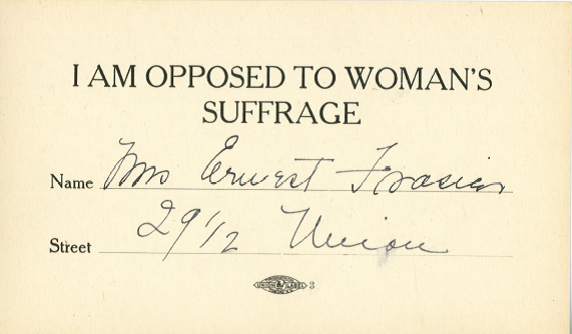

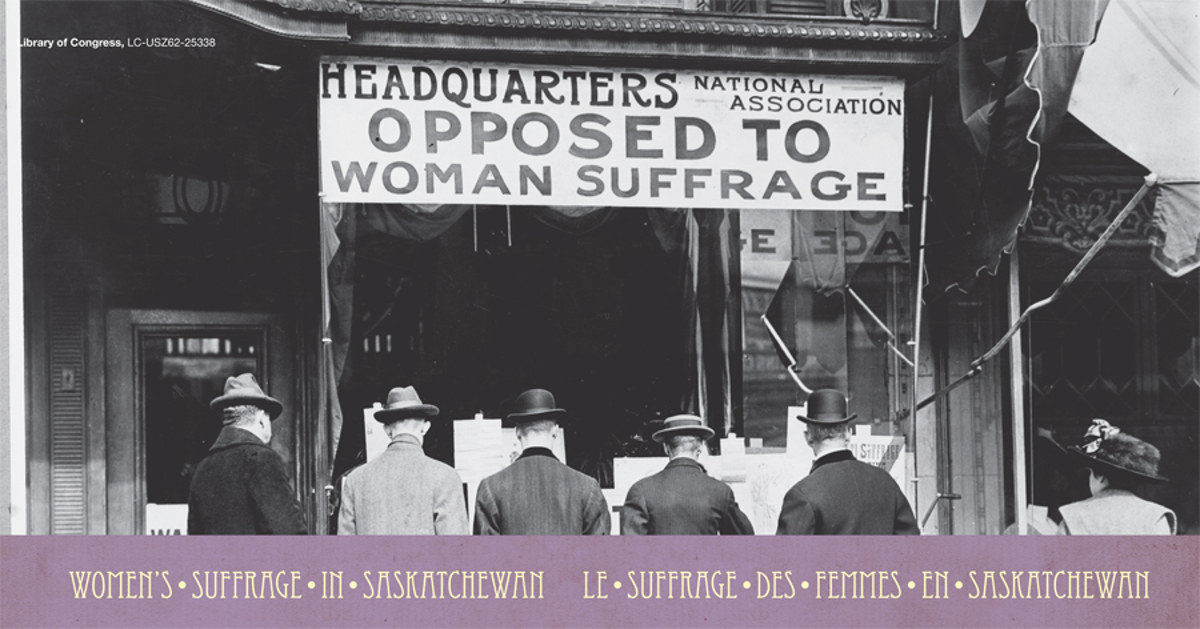

Rejecting the Cause

Opposition to the suffrage movement came not just from men, but also from some women.

Opposition to the suffrage movement came not just from men, but also from some women.

Anti-suffragists condemned “the cause” because they believed voting would lead to family discord and the breakdown of a woman’s “proper role.” Some claimed that as mothers and homemakers, women did not need to understand political affairs. Others argued that women were not intelligent enough to engage in politics. Believing that only men had the knowledge and experience to grasp complex issues, critics said women would always vote as their husbands did, so there was no need to give them their own ballot. Anti-suffragists also said that women did not actually want the vote, and even if they had it, would not use it.

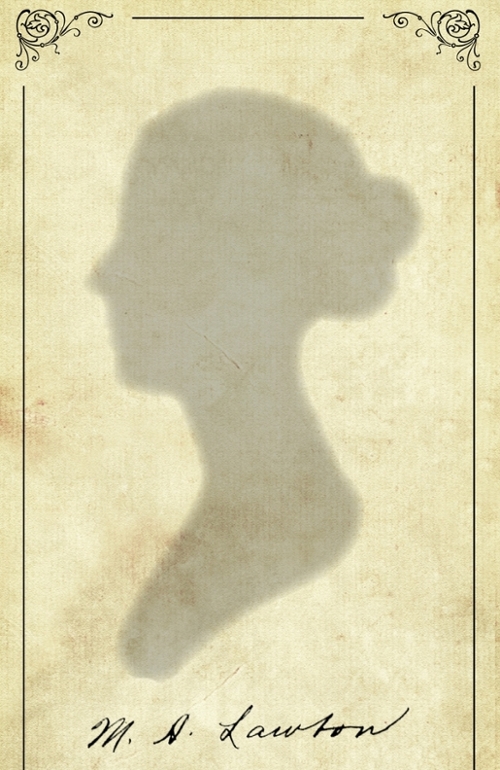

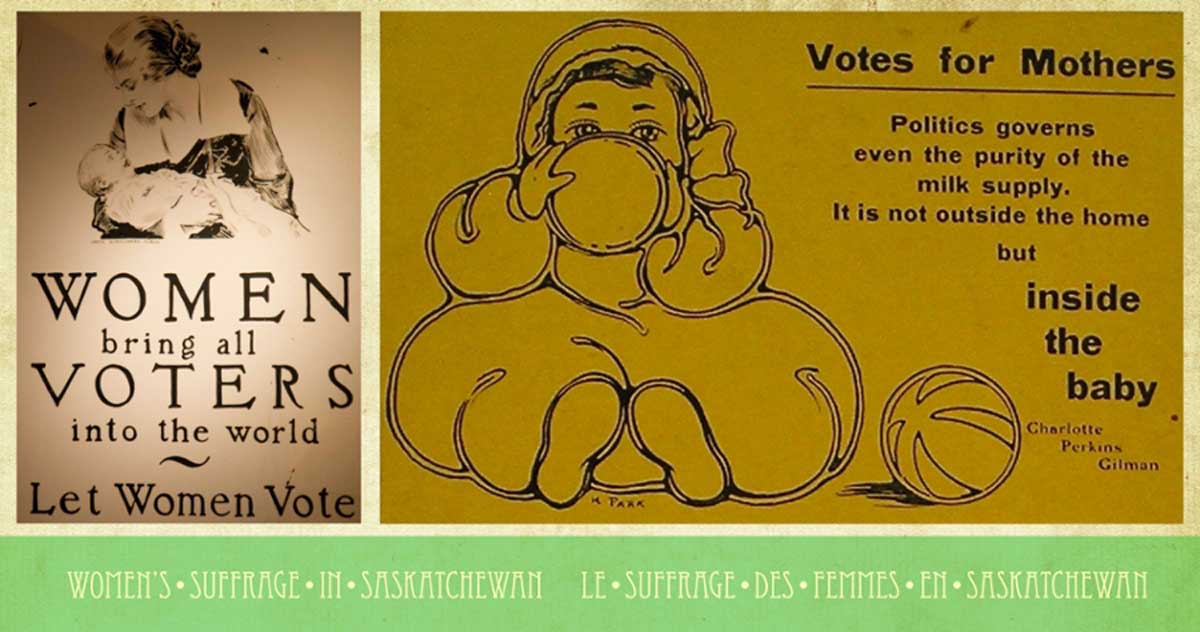

Why Women Ought to Vote

Suffrage supporters responded to anti-suffragists by stating that they did not want to disrupt gender roles. Rather, they wanted the vote so as to increase political representation of women’s issues. Most argued that suffrage did not challenge notions of women as primary caregivers and homemakers, but instead strengthened these ideals by promoting women’s political involvement.

Violet McNaughton, Saskatchewan’s primary suffrage leader, pointed out that many men who had the franchise did not vote, but they were not judged as being unfit voters. She said that, “women would vote just as men did: some would vote well, others would vote poorly, and others still would not use it at all.”

For Hearth and Home

“Maternal feminism” was a philosophy that stated women were natural advocates for the welfare of children and families because they were instinctively more nurturing. Suffragists who agreed with this idea claimed that their purpose in agitating for suffrage was not to upset the social order, but to improve it.

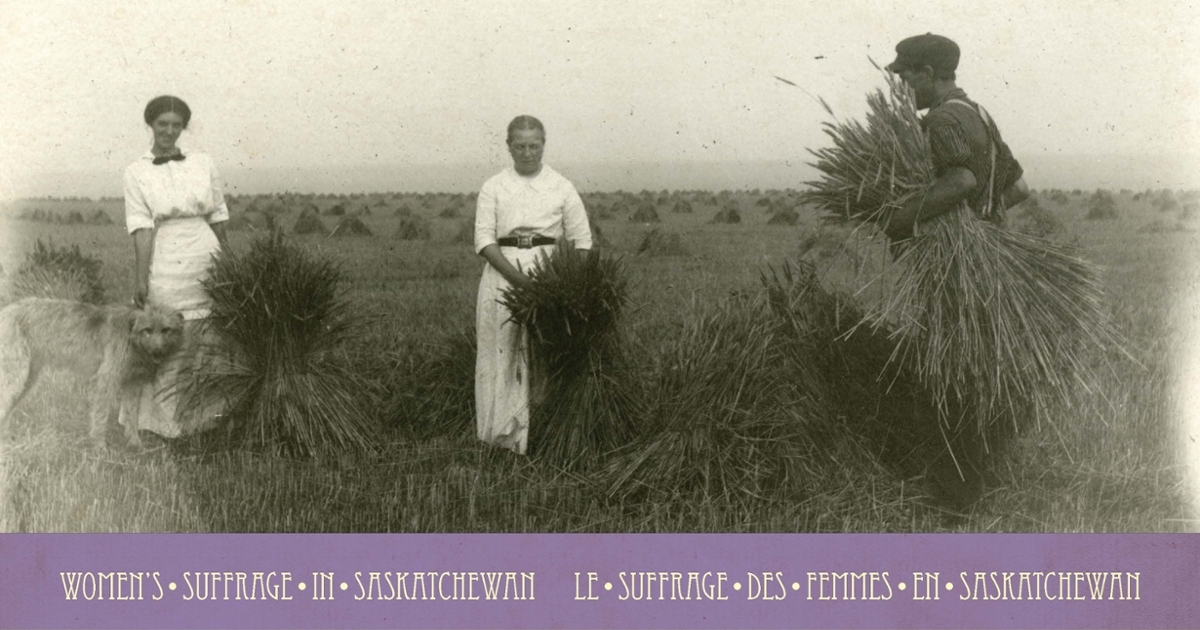

Maternal feminism also claimed that men and women occupied “separate spheres” — men were responsible for public affairs outside the home, while women took care of domestic tasks. These “spheres” were not so clearly defined in Saskatchewan, however, where women often participated in farm labour, just like men. Farm men and women saw each other not as competitors, but as partners in the struggle to improve rural life for everyone.

|

|

Mothers of the Race

Maternal feminism included a belief in “racial purity.” In the early 1900s, the growing immigrant population concerned many Anglo-Canadian women, especially in urban areas.

Maternal feminism included a belief in “racial purity.” In the early 1900s, the growing immigrant population concerned many Anglo-Canadian women, especially in urban areas.

Seeing themselves as genetically superior, these women felt a responsibility as “mothers of the race” to have children and raise “proper” British families. Some even went as far as to suggest that what society needed was racial preservation and advancement.

The Saskatchewan Women Grain Growers’ Association, however, recognised the importance of recruiting support for the suffrage movement. They made efforts to include and educate immigrant farmwomen of non-British descent. Violet McNaughton believed that Grain Growers members had, “a part to play in our duty to the so-called ‘foreign’ women who, like ourselves, are now ‘citizens’.”

Challenges

Class Divides

While suffragists remained united in one goal, there were also divisions between social classes, especially in urban areas. In larger cities, the strongest supporters came mostly from the middle class. These women felt they had an obligation to lead the working class to a better life. However, many urbanites could not relate to the women they were trying to “help,” and did not see them as equals. Working-class women recognized these patronizing views and were skeptical of such aid.

Class divides were much less obvious in Saskatchewan, where even in urban areas there was more affinity with rural women. Many suffragists in the province were farmwomen whose leaders came from co-operative movements where partnerships and solidarity were encouraged.

Regional Challenges

Regional divides were also evident within the suffrage movement, specifically between the Canadian “East” (mainly Ontario), and “West” (primarily the prairies). Many women in Eastern Canada moved to large cities looking for better opportunities, but found living was difficult and expensive. Some were forced to work under hazardous conditions in order to support themselves or to supplement family incomes. The fewer women on the prairies found

Regional divides were also evident within the suffrage movement, specifically between the Canadian “East” (mainly Ontario), and “West” (primarily the prairies). Many women in Eastern Canada moved to large cities looking for better opportunities, but found living was difficult and expensive. Some were forced to work under hazardous conditions in order to support themselves or to supplement family incomes. The fewer women on the prairies found

husbands and started families quickly. These women were valuable partners in maintaining homesteads and assisting with manual labour. Therefore, for rural men, accepting their wives as equals and supporting the movement came fairly easily. However, women who did not secure “good marriages” were left vulnerable because laws regarding property ownership strongly favoured men.

Town and Country

Some women in rural Saskatchewan approached urbanites with suspicion and skepticism because they often seemed to not fully understand the struggles of farmwomen. Leading provincial suffragists tried to bridge this gap by creating inclusive organisations. Violet McNaughton, for instance, established the Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board. Others started branches of Provincial Equity Leagues, and the Saskatchewan Women’s Christian Temperance Union was a commanding presence. Although some of these associations were heavily represented by urbanites and others by rural women, they all had similar end goals. They all advocated for prohibition, improved rural health care, agrarian advancement, gender equality, labour parity, social reform, and, of course, suffrage.

Pulling Together

Organization and Cooperation

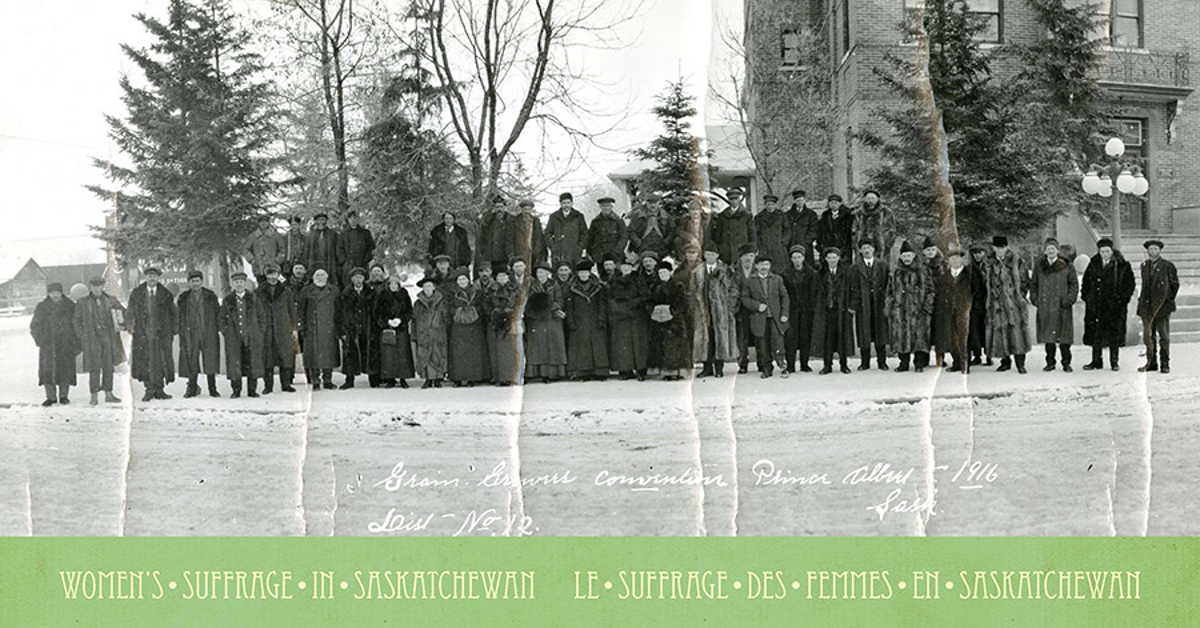

Suffrage associations, such as the Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board, were rare in rural areas. Instead, these women were more likely to become members of farm associations that preceded the suffrage movement. Members of these groups included those who became heavily involved in “the cause.” As a result, these organizations were central to suffrage activities. Men supporting the movement typically saw enfranchisement as a way to further influence the provincial government for genuine change. Rural men also viewed the extension of the franchise to women as another way to strengthen their political representation in urban centres.

Pulling Together

Other Saskatchewan organizations helped women achieve the franchise. The varied purposes of these entities — prohibition, health care, agrarian advancement, gender equality, labour parity, and social reform — represented most women in the province, whether they were in urban or rural areas. As off-shoots of larger inter-provincial and national associations, these groups grew under the direction of leading provincial suffragists Violet McNaughton, Zoa Haight, Alice Lawton, Annie Hollis, Erma Stocking, and the Beynon sisters, Lillian and Francis. Spearheaded by these women, the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association, the Women Grain Growers’ Association, the Saskatchewan Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and the Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board all developed into distinctly Saskatchewan entities.

Shoulder to Shoulder

Rural women in Saskatchewan organized and promoted the suffrage movement almost entirely through agrarian organizations. Of these groups, the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association was the largest and most supportive. Established in the early 1900s to lobby the provincial and federal governments for agricultural reform, members included both men and women.

The Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association produced a newspaper called “The Grain Growers’ Guide,” which distributed news throughout rural Saskatchewan until the mid-1920s. The Guide included a popular women’s section, which published stories, letters to the editor, recipes, poetry, and household tips. The section became a forum for women to share their grievances, experiences, ideas, and advice with each other. It became a way for women who lived in isolation to support one another and discuss the franchise.

Growing Women's Activism

In 1914, Violet McNaughton created a strictly women’s organization from the Saskatchewan Grain Growers’ Association. It was called the Saskatchewan Women Grain Growers’ Association, and Violet became the first President. Under her leadership, and with help from Zoa Haight and other women leaders, the Women Grain Growers’ Association grew into more than just an offshoot of its parent Association. Working together, the Women Grain Growers’ and the Grain Growers’ associations became the dominant champions of women’s suffrage in Saskatchewan. Amongst other things, the Women Grain Growers’ Association was also instrumental in creating a rural health care system, including hiring district doctors and nurses, establishing libraries, and securing various laws that protected the rights of women and children.

A Sobering Stance

The connection between the temperance movement and suffrage was especially close. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union was instrumental in the promotion and success of the suffrage cause. Originating in urban areas, Union chapters quickly appeared in Saskatchewan in the early 1900s.

Many urban and rural women viewed the use of alcohol as the root of domestic violence, unemployment, poverty, and the disintegration of families. Women’s Christian Temperance Union leaders, however, recognized that their members were mainly women who lacked political influence. They partnered with provincial suffrage groups, believing that once the franchise was secured, women would vote for prohibition. Inevitably, women who were drawn to one organization often became members of the other.

Voices and Votes

On February 14th, 1916, the Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board presented a petition with 10,000 signatures in favour of women’s suffrage to Saskatchewan Premier Walter Scott. The provincial franchise for women was officially granted exactly one month later, on March 14th. Women first voted provincially on June 26th, 1917. This election included Saskatchewan’s first female electoral candidate, Zoa Haight, who ran as a non-partisan candidate in the district of Thunder Creek. This election caused some division in the Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board. Many supported the Liberals, while others, including Zoa Haight and Violet McNaughton, thought that reform could only come through non-partisan parties. The election resulted in a landslide victory for the Liberals.

On February 14th, 1916, the Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board presented a petition with 10,000 signatures in favour of women’s suffrage to Saskatchewan Premier Walter Scott. The provincial franchise for women was officially granted exactly one month later, on March 14th. Women first voted provincially on June 26th, 1917. This election included Saskatchewan’s first female electoral candidate, Zoa Haight, who ran as a non-partisan candidate in the district of Thunder Creek. This election caused some division in the Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board. Many supported the Liberals, while others, including Zoa Haight and Violet McNaughton, thought that reform could only come through non-partisan parties. The election resulted in a landslide victory for the Liberals.

Listen to Alice Lawton's historic address to Premier Scott upon presenting the petition.

Listen to Premier Walter Scott's response to the delegation.

The Regina Morning Leader broadcasted the news the next day; listen to "Women Recieve the Vote."

A Changing World

Gender roles changed dramatically after the outbreak of the Great War. As women began to replace men who left to serve in the armed forces, new opportunities arose for them to work in jobs that had previously been exclusively men’s. The positions they filled helped to meet the increased demands for food production, industrial activities, and manufacturing. In rural Saskatchewan, women took over farm labour, and in the cities many went to work in factories. The War brought societal changes, but it also divided prairie suffragists. The Beynon sisters for instance, were staunch pacifists. Others, like Violet McNaughton, were “patriotic pacifists” who disagreed with Canada’s participation in the War, but remained loyal to Britain and assisted with the War effort.

Gender roles changed dramatically after the outbreak of the Great War. As women began to replace men who left to serve in the armed forces, new opportunities arose for them to work in jobs that had previously been exclusively men’s. The positions they filled helped to meet the increased demands for food production, industrial activities, and manufacturing. In rural Saskatchewan, women took over farm labour, and in the cities many went to work in factories. The War brought societal changes, but it also divided prairie suffragists. The Beynon sisters for instance, were staunch pacifists. Others, like Violet McNaughton, were “patriotic pacifists” who disagreed with Canada’s participation in the War, but remained loyal to Britain and assisted with the War effort.

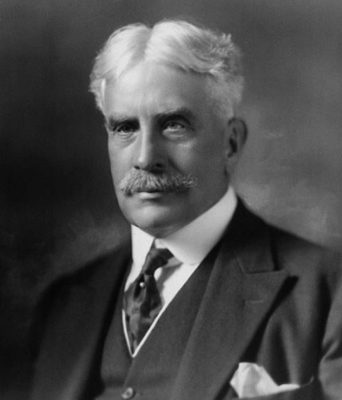

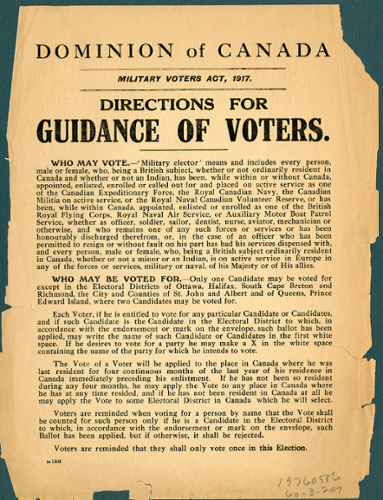

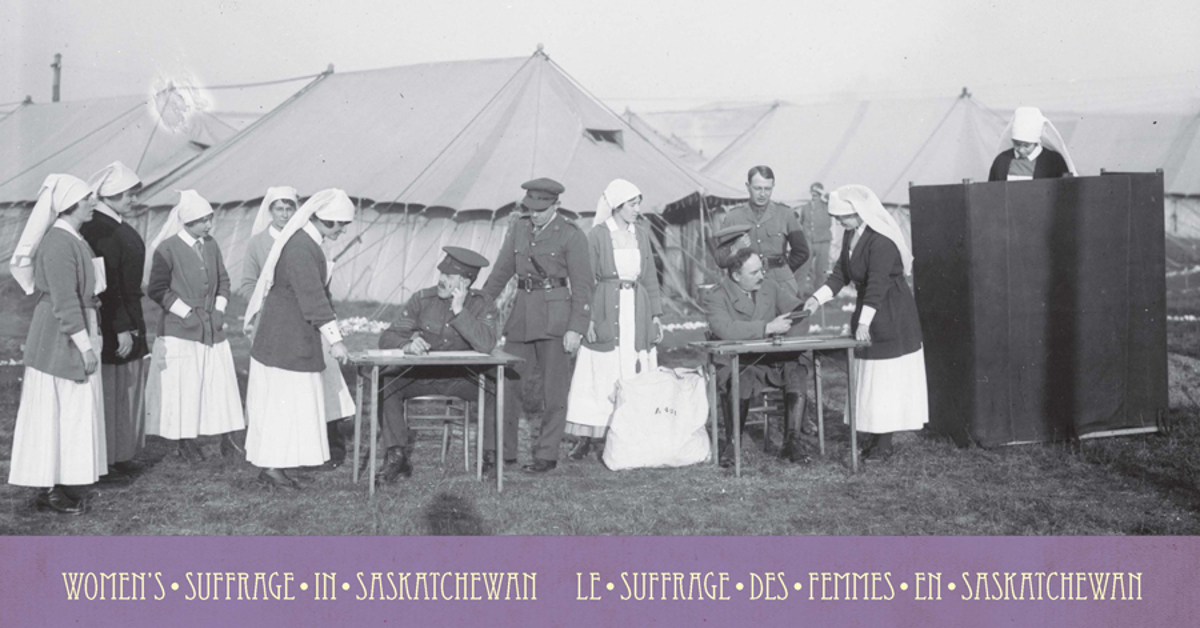

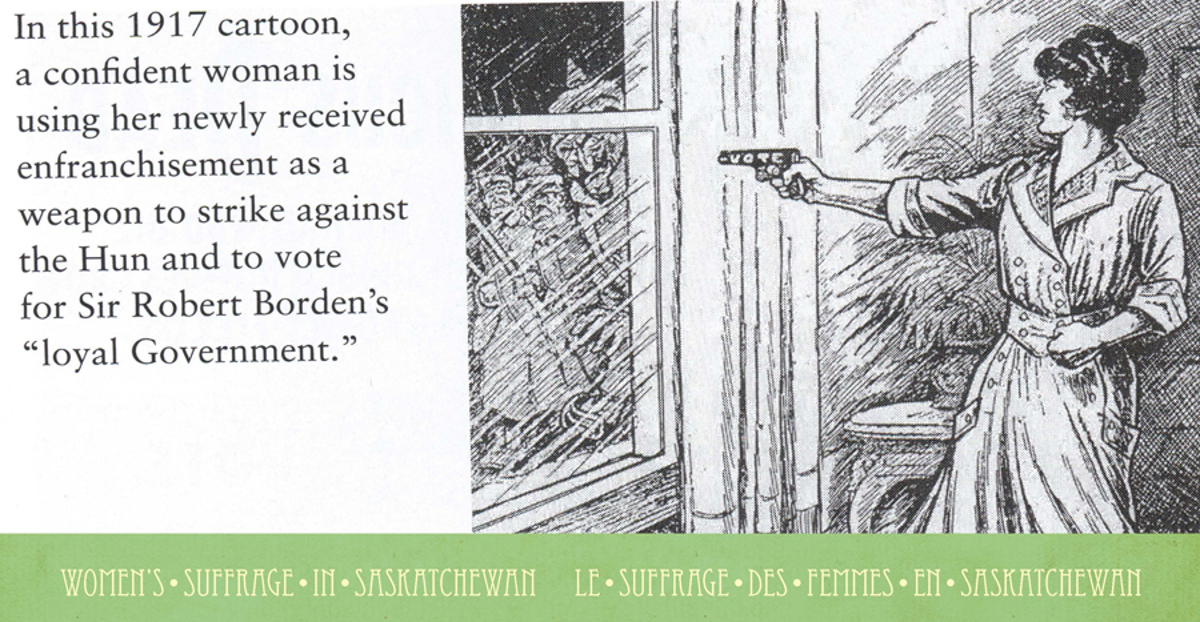

The Wartime Elections Act

The Great War was the impetus that caused the federal government to finally view the suffrage movement seriously.

The Great War was the impetus that caused the federal government to finally view the suffrage movement seriously.

In 1917, Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden had two main goals: to win the upcoming federal election and to pass a controversial Conscription Bill that would make military service mandatory for all men of fighting age in Canada. Borden realized that women with male relatives serving overseas would likely agree with conscription and could provide the support he needed to stay in office.

In September, Parliament passed the Wartime Elections Act, which extended suffrage to women of British origin who had male relatives serving in the War. The franchise was also given to 2,845 Nursing Sisters who were members of the Canadian Army Medical Corps.

The Nation Follows

Suffragists were not satisfied with the Wartime Elections Act. The Saskatchewan Equal Franchise Board openly stated that the Act undermined the suffrage cause by giving the vote to only a select few. The Beynon sisters called the partial franchise “undemocratic.”

After extending the Wartime Elections Act, it became obvious to Prime Minister Borden that he could not argue against suffrage for all women. On May 24, 1918, Canadian women over the age of 21 who owned property received the right to vote in federal elections.

However, for some women, the fight for suffrage did not end there. The 1918 federal vote was not extended to Indigenous women or to women from racial minorities.

Expanding Democracy

Left Behind

Under the Indian Act of 1876, status Indians were considered “wards of the state” and not full citizens, so they were excluded from voting.

Under the Indian Act of 1876, status Indians were considered “wards of the state” and not full citizens, so they were excluded from voting.

In 1960, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker gave the federal vote to all Indigenous people. Shortly after, Saskatchewan Premier Tommy Douglas extended provincial voting rights to Saskatchewan’s Indigenous people.

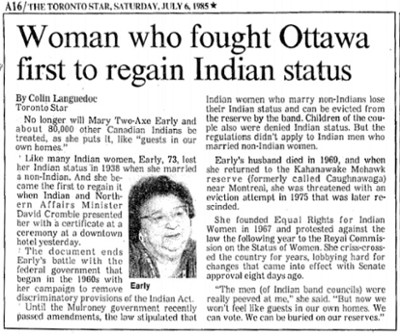

However, discriminatory enfranchisement policies continued, especially for Indigenous women. Until 1985, if a First Nations woman married a “non-Indian” man, she and her children lost their Indian rights and status. On the other hand, if a non-Indigenous woman married a First Nations man, she legally became an “Indian,” and until 1960 this made her ineligible to vote.

Bill C-31

In 1985, Bill C-31 was added to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Bill removed the discriminatory practice of denying an Indigenous woman her rights if she married a “non-Indian” man. After the Bill came into effect, Indigenous women and their children could apply to have their lost status reinstated. However, this was an extremely difficult process. Applicants had to travel to Department of Indian Affairs offices, which was unaffordable for many women living in remote communities. Also, there were additional research fees for finding evidence that a woman was Indigenous. Therefore, despite Bill C-31, the process of regaining status was still out of reach for women who were financially, or otherwise, disadvantaged.

Excluded

The situation did not change for women from visible minorities after provincial and federal suffrage was secured. Racial discrimination excluded Chinese-Canadians, Japanese-Canadians and Indo-Canadian women, as well as men, from voting until well into the 1940s.

The situation did not change for women from visible minorities after provincial and federal suffrage was secured. Racial discrimination excluded Chinese-Canadians, Japanese-Canadians and Indo-Canadian women, as well as men, from voting until well into the 1940s.

In 1920, a clause in the Dominion Elections Act removed federal voting rights for individuals who were provincially disenfranchised based on race. Saskatchewan was one of the only two Canadian provinces to deny Chinese-Canadians the provincial vote. Chinese-Canadians and Indo-Canadians were provincially and federally enfranchised in 1947, and Japanese-Canadians in 1948.

Doukhobors and Mennonites also faced intolerance. The Wartime Elections Act of 1917 disenfranchised them based on religious beliefs that opposed military participation. Mennonites regained the vote in 1920, whereas Doukobors were not allowed to vote until 1955.

Conclusion

Triumphs and Trials

While suffrage was a major success for women’s rights in Saskatchewan, it also brought some disappointments for the women who had worked so hard to see it achieved.

While suffrage was a major success for women’s rights in Saskatchewan, it also brought some disappointments for the women who had worked so hard to see it achieved.

Many suffragists expected women to exercise their newfound political voice to enact laws that would address the social problems they had fought against, and grant them legal recognition as citizens. They believed women would vote together as a unified force, but women’s voting blocs never gained much strength.

Ironically, the very thing that suffragists fought for — to let women think for themselves and vote for their chosen representatives — was the very thing that prevented the political unity they sought.

In truth, just like men, women disagreed on many political issues and remained divided along traditional ideological and party lines.

A legacy

Today, voting is one of the most fundamental rights of Canadian citizenship. However, for women this right was hard won. In the early 1900s Violet McNaughton, Zoa Haight, and their sister suffragists united to achieve what people said could not be done — equal franchise. While divisions and challenges remained following the granting of the vote, the foundation for women’s rights had been laid.

The term “women suffragists” is no longer used, but regardless of how women activists describe themselves today, they continue to work toward goals that were started by the women who came before them: gender equity and political parity.

Acknowledgements

Exhibits do not create themselves, and our ability to share the stories in “Sisters United: Women’s Suffrage in Saskatchewan” is due to the support of many individuals and organizations.

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Government of Canada through the Museums Assistance Program.

For sharing their expertise, our sincere thanks go out to Dr. L. Biggs, Dr. K. Carlson, Dr. E. Dyck, Dr. B. Fairbairn, Dr. L. Hammond Ketilson, Dr. V. Korinek, Dr. M. Lovrod, and Dr. W. Roy, and Ms. A. Kreuger, from the University of Saskatchewan, Dr. S. Carter from the University of Alberta, Dr. R. Sawatzky from the Manitoba Museum, and Dr. V. Strong-Boag from the University of British Columbia. Your guidance, encouragement and valuable critiques were instrumental to the success of this project.

Furthermore, we recognize our partnering cultural and heritage institutions. Especially, the Canadian War Museum/Musée Canadien de la Guerre, the Grand Coteau Heritage and Cultural Centre, Library and Archives Canada/Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan, the Saskatchewan History and Folklore Society, the University of Saskatchewan Archives and Special Collections, and the Western Development Museum. Your support of this project and generous loans will allow visitors to connect with captivating artefacts, making “Sisters United” a more dynamic and compelling exhibit.

Finally, we extend our thanks to all the other individuals whose dedication and efforts contributed to the production of “Sisters United.”