This exhibit focuses on the Canadian Bill of Rights and Diefenbaker’s role in shaping what it means to be Canadian.

“I am a Canadian, a free Canadian.”

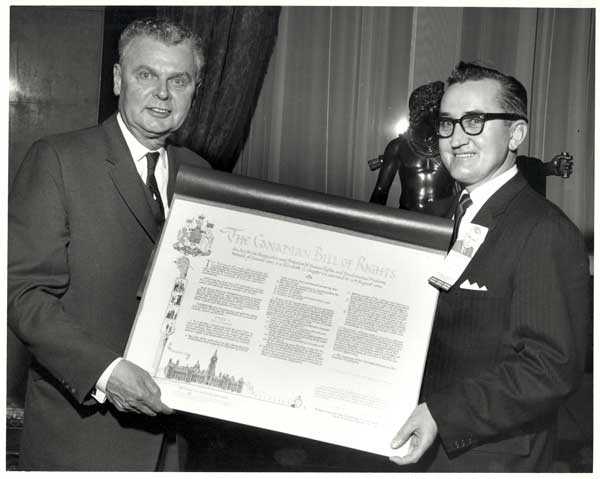

This statement is found in the Canadian Bill of Rights, a piece of legislation which The Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker acknowledged as one of his proudest achievements. The Canadian Bill of Rights was created in an effort to give Canadians of all backgrounds the same rights and privileges.

To this day, the saying “I am Canadian” invokes strong sentiments based on the understanding that Canadian law acknowledges the equality of all citizens.

"I am Canadian, a free Canadian, free to speak without fear, free to worship God in my own way, free to stand for what I think right, free to oppose what I believe wrong, free to choose those who govern my country. This heritage of freedom I pledge to uphold for myself and all mankind."

(John Diefenbaker, House of Commons Debates, 1 July 1960)

On 10 August 1960, Her Royal Highness Queen Elizabeth II granted Royal Assent to the Canadian Bill of Rights. The Bill represented a monumental step towards legitimizing the rights and privileges of all Canadians. 50 years later, the Bill is regarded as a declaration symbolizing a national history of dedication to civil liberties.

|

|

|

Laying the Foundation

"From my earliest days, I knew the meaning of discrimination. Many Canadians were virtually second-hand citizens because of their names and racial origin. Indeed, it seemed until the end of World War II that the only first-class Canadians were either of English or French descent. As a youth, l determined to devote myself to assuring that all Canadians, whatever their racial origin, were equal and declared myself lo be a sworn enemy of discrimination."

(John Diefenbaker, Nowlan Lecture, 6)

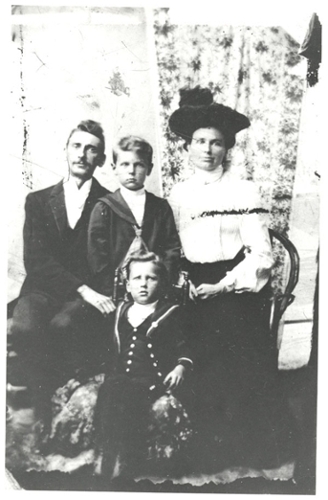

Diefenbaker was born in Neustadt, Ontario on 18 September 1895. In 1903, the Diefenbakers moved to an area of the Northwest Territories that later became the province of Saskatchewan. His mother was Scottish and his father, a German immigrant, experienced discrimination during the First World War.

Raised among many other immigrant settlers with similar experiences of hardship and prejudice, Diefenbaker saw the importance of equality from an early age. The bigotry and discrimination that he witnessed against First Nations and Métis communities further influenced his belief that the freedom and rights of all Canadians should be protected.

Diefenbaker would become the first Canadian Prime Minister of neither English nor French descent.

|

|

|

Setting the Bar

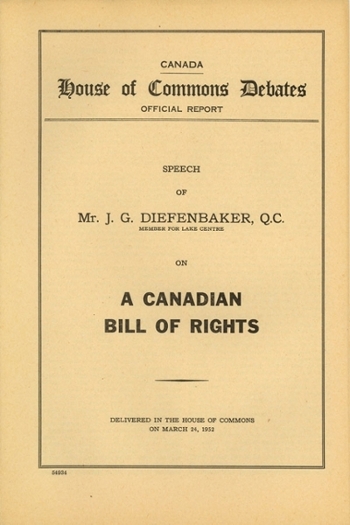

"In my days as a young lawyer I began the drafting of a Canadian Bill of Rights"

"In my days as a young lawyer I began the drafting of a Canadian Bill of Rights"

(John Diefenbaker, One Canada, Volume Two, 208).

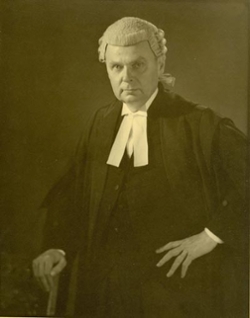

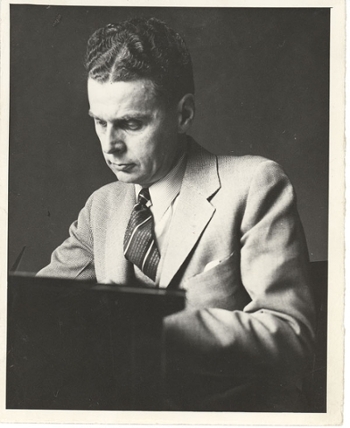

Early in his career, Diefenbaker was an advocate for minorities and a proponent of civil rights. One of his first widely-publicised court cases involved two school trustees from the Ethier School District: Rémi Ethier and Léger Boutin. The men had been charged of violating the Saskatchewan School Act by allowing classes to be taught in French. Diefenbaker was successful as their counsel in appealing the accusation.

Within the first four years of his law practice in Wakaw, Saskatchewan, Diefenbaker “dominated [the] legal business" in the area of human rights. (Denis Smith, Rogue Tory, 41) Few people were able to secure legal council for human rights claims, as they were incredibly costly. To ensure individuals were guaranteed their rights, Diefenbaker made special efforts to undertake legal cases involving violations of individual rights. In such situations, it was rare that legal fees would be collected on time, if at all.

"As a young boy, I had set my mind on becoming a lawyer. My ambition was now realized. What my boyish determination had not included was an understanding that a call to the bar was a beginning, not an end....”

(John Diefenbaker, One Canada, 87)

|

|

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Canada Leads the Cause

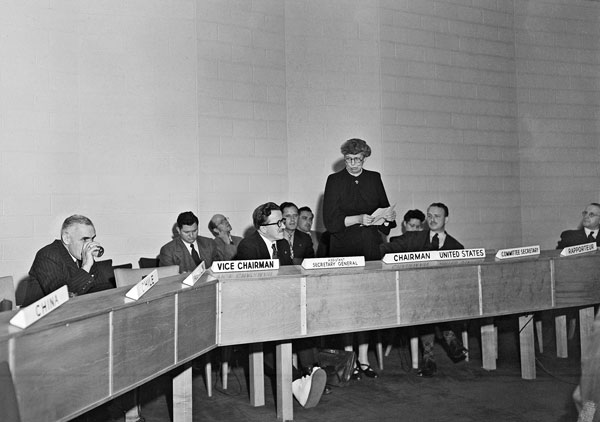

The human rights atrocities associated with the Second World War motivated world leaders to acknowledge the need for establishing an internationally recognized document safeguarding universal civil liberties. John Peters Humphrey, a Canadian law professor, was one of two authors who wrote the preliminary draft of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Declaration was officially adopted on 10 December 1948 by the United Nations. The UN asserted that the international community as a whole was responsible for the protection of individual human rights and the assurance of non-discrimination. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights continues to be used today by the United Nations and is "protected by the rule of law." (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Preamble)

The human rights atrocities associated with the Second World War motivated world leaders to acknowledge the need for establishing an internationally recognized document safeguarding universal civil liberties. John Peters Humphrey, a Canadian law professor, was one of two authors who wrote the preliminary draft of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Declaration was officially adopted on 10 December 1948 by the United Nations. The UN asserted that the international community as a whole was responsible for the protection of individual human rights and the assurance of non-discrimination. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights continues to be used today by the United Nations and is "protected by the rule of law." (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Preamble)

"All human beings are born with equal and inalienable rights and fundamental freedoms. ...the United Nations Charter... reaffirms the faith of the peoples of the world in fundamental human rights and the dignity and worth of the human person.”

(Universal Declaration of Human Rights, United Nations Department of Public Information, 2008)

Canada's prominent role as a principal author of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a reflection of events in the nation at that time. One year before the Declaration, the province of Saskatchewan passed the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights, which protected people of the province from infringements on human rights. In 1946, Diefenbaker had called for a bill of rights in the Canadian Parliament.

Canada's prominent role as a principal author of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a reflection of events in the nation at that time. One year before the Declaration, the province of Saskatchewan passed the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights, which protected people of the province from infringements on human rights. In 1946, Diefenbaker had called for a bill of rights in the Canadian Parliament.

Diefenbaker had been earnestly campaigning for the protection of individual rights and freedoms since becoming a Member of Parliament in 1945. His proposed amendment to the Canadian Citizenship Act appealed for the incorporation of basic rights such as freedom of speech, freedom of religion, the right to peaceable assembly, and the right to legal counsel when giving evidence.

Read ‘The PM’s Bill of Rights Freedom’s Advocate’

Listen to ‘Speech by John Diefenbaker at the Young Progressive Conservative Convention, Ottawa’

Challenges at Home

Following the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Canada was perceived internationally as a strong ally in the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms. However, on a national level, Canadians had their own challenges.

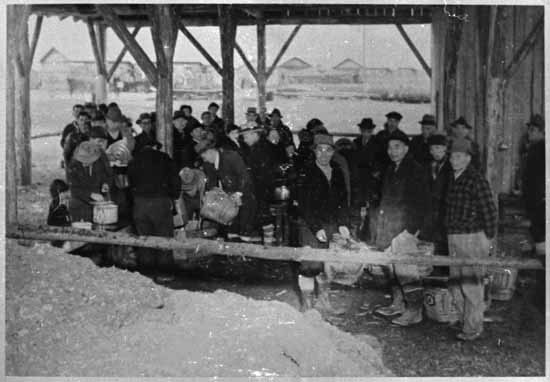

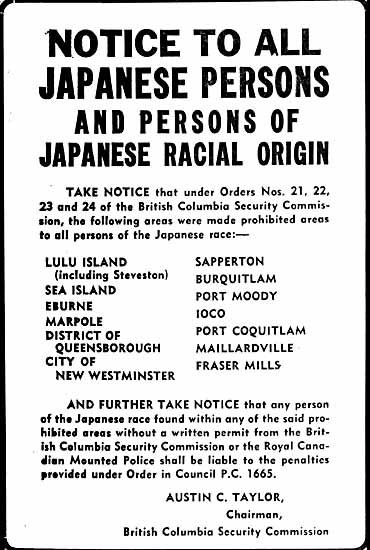

After the Second World War, controversy over the internment of Japanese Canadians before and during the war was brought to the forefront by the national press. Canadians of Japanese descent, mainly from coastal British Columbia, had been forcibly relocated due to fears of conspiracy with the Japanese Empire. Almost 23,000 people, three-quarters of whom were naturalized or native-born citizens, were removed from their homes and had their property auctioned, with the proceeds being retained by the government. Some male detainees were sent to work camps, while others were interned in prisoner of war camps. Using the War Measures Act, the Liberal government passed an order-in-council suspending habeas corpus, which resulted in citizens being imprisoned without charges having been laid.

As a Member of Parliament, Diefenbaker led the House Committee on the Defence of Canada Regulations. The Committee investigated instances where arrests and detentions without a trial occurred during the War. Diefenbaker strongly opposed Prime Minister Mackenzie King's decision to displace and intern Japanese Canadians. He argued that such decisions should be made through parliamentary debate, rather than by orders-in-council. In his view, only Parliament - not the Executive - had the right to legislate in a manner that violated civil liberties. (Parliamentary Democracy and the Canadian Bill of Rights - The Diefenbaker Legacy, 101)

As a Member of Parliament, Diefenbaker led the House Committee on the Defence of Canada Regulations. The Committee investigated instances where arrests and detentions without a trial occurred during the War. Diefenbaker strongly opposed Prime Minister Mackenzie King's decision to displace and intern Japanese Canadians. He argued that such decisions should be made through parliamentary debate, rather than by orders-in-council. In his view, only Parliament - not the Executive - had the right to legislate in a manner that violated civil liberties. (Parliamentary Democracy and the Canadian Bill of Rights - The Diefenbaker Legacy, 101)

Saskatchewan Bill of Rights

A National First

In 1947, the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights Act was introduced to the Legislative Assembly and was passed the same year. Morris Shumiatcher wrote the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights during Premier Tommy Douglas’ tenure as Saskatchewan’s seventh Premier. It preceded the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is recognized as the first bill of its kind legislated in Canada.

In 1947, the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights Act was introduced to the Legislative Assembly and was passed the same year. Morris Shumiatcher wrote the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights during Premier Tommy Douglas’ tenure as Saskatchewan’s seventh Premier. It preceded the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is recognized as the first bill of its kind legislated in Canada.

“The Saskatchewan Bill of Rights did not deal only with human rights, but with the political civil liberties as well.... It also prohibited discrimination.... A large distinction was that it bound the Crown and every servant and agent of the Crown. There were penal sanctions such as fines, injunction proceedings and imprisonment for non-compliance.”

(Walter Surma Tarnopolsky, The Canadian Bill of Rights, 67)

Like Diefenbaker, Douglas was a staunch supporter of freedom and equality rights, a dedication which stemmed from experiences in his youth. As a young man, Douglas almost lost a leg because his family could not afford the required medical aid. He also witnessed police oppression and abuse during the Winnipeg General Strike in 1919. A dedicated civil libertarian and advocate of social welfare, Douglas defended the disadvantaged, underprivileged and exploited.

Douglas strongly supported the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights, which included the protection of: freedom of conscience, opinion, religion and expression; freedom to engage in peaceable assembly and association, and protection from arbitrary arrest and detention; freedom from discrimination in employment, occupations and businesses, accommodation and services, and professional associations and unions. The Bill provided legal impetus for Diefenbaker in his vision to create the Canadian Bill of Rights.

Douglas strongly supported the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights, which included the protection of: freedom of conscience, opinion, religion and expression; freedom to engage in peaceable assembly and association, and protection from arbitrary arrest and detention; freedom from discrimination in employment, occupations and businesses, accommodation and services, and professional associations and unions. The Bill provided legal impetus for Diefenbaker in his vision to create the Canadian Bill of Rights.

Read ‘Provincial Bill of Rights Statutes – Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba’

The Long Road to a Dream

[l envision a program] "for... a united Canada, for one Canada, for Canada first, in every aspect of our political and public life, for the welfare of the average man and woman. That is my approach to public affairs. and has been throughout my life.... A Canada, united from Coast to Coast, wherein there will be freedom for the individual, freedom of enterprise, and where there will be a Government which, in all its actions, will remain the servant and not the master of the people.”

(John Diefenbaker, from Rogue Tory: The Life and Legend of John Diefenbaker, Smith, Denis (1995))

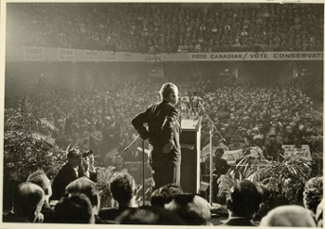

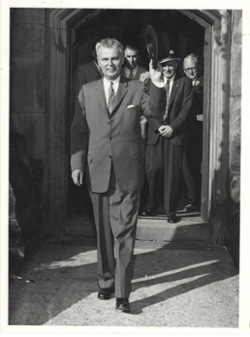

In January 1957, Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent called an election for 10 June 1957. Diefenbaker, having recently become the Leader of the Official Opposition, was left with a mere five months to plan and carry out an election campaign. Initially, the Liberals dismissed Diefenbaker, the dissenter from the Prairies who had lost countless elections throughout his attempts at a political career. However, it soon became apparent to St-Laurent that many Canadians identified with Diefenbaker’s determination and tenacity. Many were also moved by his sincere concern for the rights of the common people.

Using the slogan “It's time for a change,” Diefenbaker led one of the first campaigns in Canada that took advantage of television as a tool for promoting their platform. Diefenbaker’s speaking style was animated and dramatic - ideal for TV broadcasts. He appealed to the working classes, many of whom felt increasingly marginalized by the Liberal government. To the surprise of the Liberals, the Progressive Conservative Party won a minority government on 21 June 1957.

It spoke to Diefenbaker’s loyalty to the Crown that the 23rd Canadian Parliament was opened by HRH Queen Elizabeth II - this was the first time that a monarch had opened the Canadian Parliament in person.

Read ‘Letter from Byrne Sanders’

Read ‘Supplementary and Consolidated Suggestions Concerning the Proposed Bill of Rights’

|

|

|

Federal Firsts

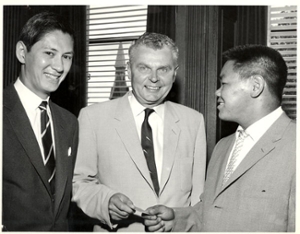

The new minority Progressive Conservative Cabinet consisted of an inexperienced group of Members of Parliament. Several of Diefenbaker's first appointments demonstrated his commitment to equality rights.

Possibly Diefenbaker’s most widely recognised appointment was Ellen Fairclough as Secretary of State. Fairclough was the first woman to sit in the Canadian Cabinet. She held several posts, including Minister of Citizenship and Immigration and Postmaster General. Fairclough advocated women’s rights, equal opportunity in the workplace, and relaxed laws limiting immigration and refugee entry into Canada. Fairclough was the first female Acting Prime Minister, though she only held this position from 19-20 February 1958. Fairclough set a precedent that paved the way for women in politics, such as Kim Campbell, Canada’s first female Prime Minister.

Diefenbaker’s Cabinet also included Michael Starr, the Minister of Labour, the first Canadian of Ukrainian descent to serve in Cabinet. As well, the newly elected Member of Parliament representing Vancouver Central, Douglas Jung, was the first Chinese Canadian to hold a post in Government. In May 1958, James Gladstone also made history, being the first status Indian appointed as a member of the Canadian Senate.

“[...] I am the first prime minister of this country of neither altogether English or French origin. So I determined to bring about a Canadian citizenship that knew no hyphenated consideration.... I am very happy in be able to say that in the House of Commons today in my party we have members of Italian, Dutch, German, Scandinavian, Chinese and Ukrainian origin -- and they are all Canadians."

(John Diefenbaker, March 29, 1958)

|

|

|

Vision of an Ideal

Prior to Diefenbaker’s minority government, the Liberals had been in power for twenty-two years. When another federal election was called for March 1958, St-Laurent was certain that his party would easily regain Parliament. However, the Liberal government underestimated the considerable public support that Diefenbaker had secured in his short eight months of power.

Prior to Diefenbaker’s minority government, the Liberals had been in power for twenty-two years. When another federal election was called for March 1958, St-Laurent was certain that his party would easily regain Parliament. However, the Liberal government underestimated the considerable public support that Diefenbaker had secured in his short eight months of power.

Promoting national development as his campaign theme, Diefenbaker promised significant federal investments in infrastructure to develop resources in Northern Canada. He also continued his “One Canada” programme, a project assuring Canadians in every region a share in the country’s prosperity. Diefenbaker appealed to the average Canadian, and his pledges captured the imagination of the nation. Disillusioned by the Liberals, and mesmerised by Diefenbaker’s vision, sincerity and oratory, thousands of people flocked to his rallies.

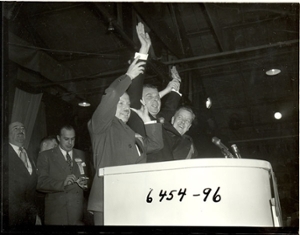

On 31 March 1958, Diefenbaker led the Progressive Conservatives to a landslide win over the Liberals. They held 208 of 265 seats in the House of Commons (53.7% of the popular vote) including 50 of 75 seats in Québec. Diefenbaker’s victory remains the largest in Canadian history, based on a percentage of the total seats in the House of Commons. Following the election, Diefenbaker wasted no time in moving toward fulfilling his vision of creating a Canada that promoted fundamental rights and freedoms.

“One Canada, one Canada, where Canadians will have preserved to them the control of their own economic and political destiny. Sir John A. Macdonald gave his life to this party. He opened the West. He saw Canada from east to west. I see a new Canada - a Canada of the North!"

“One Canada, one Canada, where Canadians will have preserved to them the control of their own economic and political destiny. Sir John A. Macdonald gave his life to this party. He opened the West. He saw Canada from east to west. I see a new Canada - a Canada of the North!"

(John Diefenbaker, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 12 February 1958)

Read ‘Should Canada have a Bill of Rights?’

Read ‘Our Bill of Rights’

Creating the Canadian Bill of Rights

The Ideal as Reality

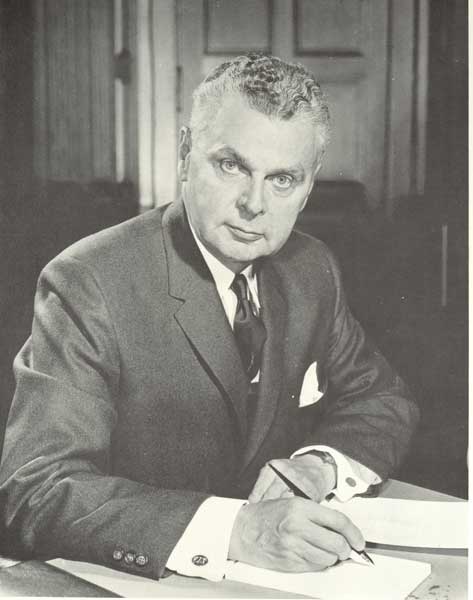

Winning a majority government provided an opportunity for Prime Minister Diefenbaker to fulfill his lifelong ideal of creating a Canadian Bill of Rights. Drafts of the Bill began appearing in earnest shortly after Diefenbaker took office. After years of experience in championing the rights and freedoms of Canadians, Diefenbaker had a clear vision of what he wanted the Bill to include.

Listen to ‘Speech by John Diefenbaker to the Progressive Conservative Women’s Association, Ottawa’

“The Parliament of Canada, affirming that the Canadian Nation is founded upon principles that acknowledge the... dignity and worth of the human person... in a society of free men and free institutions;

Affirming also that men and institutions remain free only when freedom is founded upon respect for moral and spiritual values and the rule of law;

And being desirous of enshrining these principles and the human rights and fundamental freedoms derived from them, in a Bill of Rights which shall reflect the respect of Parliament for its constitutional authority and which shall ensure the protection of these rights and freedoms in Canada:

Therefore Her Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate and House of Commons of Canada, enacts [The Canadian Bill of Rights].”

(The Canadian Bill of Rights)

It took a short two years for the Bill to evolve into the final version that was presented to Parliament on 1 July 1960. On 10 August, only one month after its introduction, the Canadian Bill of Rights was passed and received Royal Assent.

The Canadian Bill of Rights was a revolutionary piece of legislation. It was the Federal Government’s first attempt at legislating rights and freedoms at a national level and it had an immediate influence on Parliament.

Read ‘Letter from Davie Fulton to John Diefenbaker’

Read ‘Letter from T.C. Douglas to John Diefenbaker’

Read ‘186000-8: Bill of Rights- Amendment to Constitution’

|

|

|

Policies in Transition

"...l [accepted cases]... where I thought someone’s rights were being violated... From the beginning of my practice, I never charged a Métis or an Indian who came to me for advice. I was distressed by their conditions, the unbelievable poverty, and the injustice done them. "

(John Diefenbaker from John Diefenbaker by Arthur Slade, (2001), 15)

Diefenbaker thought that all citizens were entitled to certain essential rights, despite cultural differences, and First Nations were no exception. Throughout Diefenbaker’s political career, his government took steps to create harmony between the Federal Government and First Nations.

The Diefenbaker government’s key achievement in Aboriginal affairs was the extension of the franchise. Initially, First Nations, as federal “wards,” were not allowed to vote in federal elections. In 1960, Diefenbaker’s government amended Section 14 of the Canada Elections Act, finally giving First Nations the opportunity to vote in 1962.

|

|

The Bill Persists

Diefenbaker wanted to use the Canadian Bill of Rights to empower Parliament with the authority to protect civil liberties, which had at times been disregarded by previous governments. He argued that the whole of Parliament, and not just the Executive, was required to thoroughly debate proposed laws dealing with rights and freedoms in order to give all legislation appropriate consideration.

Diefenbaker wanted to use the Canadian Bill of Rights to empower Parliament with the authority to protect civil liberties, which had at times been disregarded by previous governments. He argued that the whole of Parliament, and not just the Executive, was required to thoroughly debate proposed laws dealing with rights and freedoms in order to give all legislation appropriate consideration.

The Bill of Rights specified that the Justice Minister was required to scrutinize and dispute any proposed legislation that was seen to breach of the rights outlined in the Bill. The Minister was then to “...report any such inconsistency to the House of Commons” for discussion and debate. (Canadian Bill of Rights, Part 1, Section 3) As part of his Cabinet, Diefenbaker appointed E. Davie Fulton as his Minister of Justice.

The first highly publicised use of the Canadian Bill of Rights was in R. v. Drybones. In 1970, Joseph Drybones, a status Indian, was convicted of being intoxicated off-reserve - a violation of the Indian Act. The Supreme court of Canada however, determined that according to the Bill, Drybones had been discriminated against based on his race. As well, his personal liberties had been infringed upon based on laws which differed from those applied to other Canadians. The Court ruled for the removal of Section 94(b) from the Indian Act.

Despite the landmark result of the Drybones case, the effectiveness of the Canadian Bill of Rights was limited to the federal level; the Bill did not have authority over provincial legislation. Neither was the Bill entrenched in the Constitution, so it could not supersede existing laws. Regardless, the Bill remains a federal statute and continues to be cited in court decisions.

"It became my abiding purpose to see every Canadian not only secure in his liberty, but secure in the knowledge of his fundamental rights and freedoms. It distressed me that those who were neither British nor French in origin were not treated with the regard that non-discrimination demands. I was even more distressed that many contended they would never become Canadians. My determination to see the Bill of Rights a reality was increased by experiences during and after the Second World War. Even now, I am still somewhat amazed at the opposition I encountered in trying to forward a Canadian Bill of Rights."

(John Diefenbaker, One Canada, Volume One, 234)

Limitations and Precedents

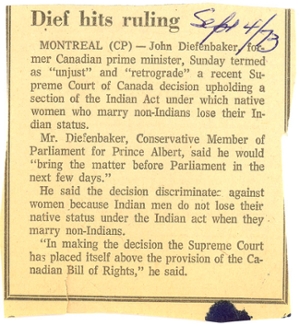

In 1974, Jeannette Vivian Corbiere Lavell brought her case before the Supreme Court of Canada. When Lavell married a non-Status man, she surrendered her Indian Status and the right to live on reserves, pursuant to the Indian Act. In the Lavell decision, the Court found that the Canadian Bill of Rights could not amend or alter the terms of the British North America Act. Therefore, the Indian Act, which was contained within the BNA Act, could only be changed if the Canadian government established new laws regarding Aboriginal Status and the use of Crown “...Lands reserved for the Indians.” (British North America Act, 1876, Section 91 (24))

“The Indian Act provided that Indian native women who marry non-Indians lose their Indian status, but if Indian males marry white women they do not. I call that discrimination.”

(Diefenbaker, Nowlan Lecture, 18 October 1973, 12)

The situation repeated itself in the Lovelace Decision. Sandra Lovelace, was a Maliseet woman from the Tobique Reserve in New Brunswick. Lovelace had married an American Airman and moved to California. Years later, Lovelace and her children returned to the Tobique Reserve and were denied housing, education and health care normally provided to those with Status under Canada's Indian Act.

Based on the precedent set by the Lavell case, Lovelace could not appeal to the Canadian courts, so she took her case to the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations. The UN declared that Canada was in breach of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. As a result, the Indian Act was revised in 1985, to ensure that Aboriginal women who married non-Status Indian men would retain their Status.

One Canada: Unity Within Diversity

Diefenbaker’s refusal to acknowledge hyphenated Canadian identities during his political career drew criticism, particularly from Québec. However, his continued commitment to national equity was evident through actions such as his recommendation to appoint Georges Vanier, Canada’s first French Canadian Governor General.

In the early 1960s, Senator Paul Yuzyk, a social historian of Ukrainian descent, was credited with popularizing the term and concept of multiculturalism – a term later associated with Pierre Elliot Trudeau. Yuzyk, whose appointment had been recommended by Diefenbaker, supported the cultural endeavours of many ethnic groups, promoting their interests in the Senate.

In the early 1960s, Senator Paul Yuzyk, a social historian of Ukrainian descent, was credited with popularizing the term and concept of multiculturalism – a term later associated with Pierre Elliot Trudeau. Yuzyk, whose appointment had been recommended by Diefenbaker, supported the cultural endeavours of many ethnic groups, promoting their interests in the Senate.

Following the Liberal Party’s electoral victory in 1963, the ideas of bilingualism and biculturalism were introduced. Diefenbaker, as Leader of the Opposition and a Member of Parliament, led Yuzyk and other politicians in condemning these policies. Diefenbaker continued to promote the ideals of multiculturalism, rather than principles that encouraged assimilation into English or French culture.

Canada is not “…a melting pot in which the individuality of each element is destroyed in order to produce a new and totally different element. It is rather a garden into which have been transplanted the hardiest and brightest flowers from many lands, each retaining in its new environment the best of the qualities for which it was loved and prized in its native land.”

(Diefenbaker, “Notes of Speech by the Prime Minister, the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker, Q.C., M.P., on the Anniversary of the Ukrainian Canadian Settlement in Canada and in Commemoration to Taras Shevchenko, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 9 July 1961”)

Listen to ‘Speech by John Diefenbaker to a Progressive Conservative banquet, Ottawa’

|

|

|

Symbol or Charter?

The Canadian Bill of Rights transformed the equality of rights and freedoms for all Canadians. All Federal bills were required to adhere to the rights guaranteed in the Bill, which had precedence where inconsistencies existed with other legislation.

Between 1977 and 1980, Harbhajan Singh and six other Sikh foreign nationals attempted to claim refugee status under the Immigration Act, on the basis of a fear of religious and political persecution in their home countries. Their petitions for refugee status were denied. In response, the Supreme Court of Canada examined the rights to which Singh et al. were entitled, and whether the assessment of their refugee status claims denied them these rights.

"Skeptics said of my proposal to have Bill of Rights, that it was an ideal, that it would be nothing but a grandiloquent declaration of freedom which would not aid any person in securing justice; that principles of substance could not be codified, and the attempt would only render Fundamental Freedoms even more obscure and uncertain."

Needs citation

The Court unanimously found that the rights of the seven foreign nationals had been violated. While the Court was in agreement, the judges were divided on whether to base their decision on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms or the Bill of Rights. Many claimed the Bill had been rendered irrelevant by the enactment of the Charter.

The Court unanimously found that the rights of the seven foreign nationals had been violated. While the Court was in agreement, the judges were divided on whether to base their decision on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms or the Bill of Rights. Many claimed the Bill had been rendered irrelevant by the enactment of the Charter.

However, the Court found that the Bill remained an effective piece of legislation based on Section 26 of the Charter, which guaranteed that any other rights and freedoms in existence in Canada cannot be denied. This provision guaranteed that the legacy of Diefenbaker’s commitment to human rights would be maintained through his proudest achievement: the Canadian Bill of Rights.

|

|

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms was entrenched in the Constitution of Canada in 1982, by Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau’s Liberal government. The Charter was designed to embody the elements previously outlined in the Canadian Bill of Rights. While the Bill was a limited federal statute, the Charter’s effectiveness lay in its being a component of the Canadian Constitution. It therefore had jurisdiction over all Canadian legislation. Although the Charter was not created during Diefenbaker's Prime Ministerial term in office, it exemplifies Diefenbaker's ideals.

"In every province we are fighting to preserve a great and precious country. The most effective weapon we have is understanding. Debates, common task forces, language programs, constitutional proposals – all these will be to little avail unless we have the ability to summon understanding and generosity towards each other’s aspirations as individuals, as members of cultural and regional communities, and as Canadians."

(Pierre Elliot Trudeau, The Report, “Let’s Hear It From the People!” Survey)

“…[No] other prime minster… did more for the cause of fairness and equality and inclusion. [Diefenbaker’s] Bill of Rights… preceded the Charter of Rights by over two decades. He extended the vote long denied to Status Indians, and appointed Canada’s first female Cabinet minister. Moreover, like Macdonald and Borden, he was a vigorous defender of Canadian sovereignty.”

(The Right Honourable Stephen Harper, “Son of the Chief,” National Post, 6 March 2007)

|

|

The Legacy

The true legacy of the Canadian Bill of Rights lies not just in its creation and historic enactment in 1960, but in the national awareness of human rights issues that it generated. (D.C. Story, “The Diefenbaker Legacy: Canadian Politics, Law and Society Since 1957,” Regina, Canadian Plain Research Centre, 1998, 120) Despite the limitations that critics saw in the legislation, the Bill substantiated the equality of rights and freedoms for all Canadian citizens.

The true legacy of the Canadian Bill of Rights lies not just in its creation and historic enactment in 1960, but in the national awareness of human rights issues that it generated. (D.C. Story, “The Diefenbaker Legacy: Canadian Politics, Law and Society Since 1957,” Regina, Canadian Plain Research Centre, 1998, 120) Despite the limitations that critics saw in the legislation, the Bill substantiated the equality of rights and freedoms for all Canadian citizens.

In 1995, on the hundredth anniversary of Diefenbaker's birth, the House of Commons Debates paid tribute to his monumental accomplishment:

“John Diefenbaker was one of those rare public figures who was larger than life and who remains larger than life. He helped define an entire era in our history. Like all Prime Ministers he left a mark on his country through his accomplishments in office, but like only a very few Prime Ministers he left a mark on our national psyche just by being the way he was. His style, his voice, his very presence have all become part of identity, part of our mythology."

Needs citation

“Mr. Diefenbaker had qualities and faults, but we have to give him credit for supporting... efforts to reach Canadians in order to promote individual freedoms. At the time, he was criticized for not supporting the Official Languages Act, but let us not forget that it is thanks to him if bilingualism was introduced in several Canadian institutions. And while he did not agree with some specific initiatives, he was always convinced of the importance of protecting individual rights. There is no doubt that John Diefenbaker helped shape Canada...”

(The Right Honourable Jean Chrétien, Debates of Sept. 18th, 1995, House of Commons Hansard #225 of the 35th Parliament, 1st Session).

“The hallmark of freedom is a recognition of the sacred personality of man, and its acceptance decries discrimination on the basis of race, or creed or colour. Canadians have a message to give to the world. We are composed of many racial groups, each of which must realize that only by forbearance and mutual respect, only by denial of antagonism or prejudice based on race, or creed, or even surname, can breaches in unity be avoided in our country. National unity in Canada is not only an ideal — it is a necessity — based on ordinary common sense."

(John Diefenbaker, "Notes for an address by the Prime Minister, The Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker, on the 'nation’s business.'" Ottawa, Ontario, 1960, 8)