Canadian Approaches to Human Rights

Canada’s approaches to human rights have developed from a long history of precedent-setting legislation and acts, but with these successes have come disappointments. The sum of these experiences have shaped and informed Canadians’ attitudes toward unity, diversity and justice — at home and internationally.

It is not difficult for each of us to think of examples of human rights issues, yet talking about them, even at the most basic level, is intimidating. People’s varied interpretations about these topics can lead to heated, emotional discussions. As Canadians, we take for granted that such debates can be carried on freely and without fear of repercussions because the rights and freedoms we enjoy are enshrined and safeguarded in our Constitution. However, how many of us are aware of how these rights appeared in this document? The way civil liberties came to be protected in Canada and how Canadians approach these topics are important questions.

Bill of Rights

Leading the Way

"I will declare the principle that every individual, whatever his colour, race or religion, shall be free from discrimination and will have guaranteed equality under the law." -Diefenbaker, 30 June 1960

"I will declare the principle that every individual, whatever his colour, race or religion, shall be free from discrimination and will have guaranteed equality under the law." -Diefenbaker, 30 June 1960

Two goals defined the vision of the Right Honourable John George Diefenbaker: attaining a truly diverse, yet united Canada (what he dubbed, "One Canada"); and the creation of a Bill of Rights. Diefenbaker's guiding principles were ground breaking in his day and they continue to shape Canada's approaches to human rights.

The enactment of the Canadian Bill of Rights on 19 August 1960 was a bold step in the protection of Canadian human rights. However, the Bill’s relevance and importance was initially questioned. Judges were uncomfortable with the way the legislation could interfere with the authority of Canada’s government given by the Constitution Act, 1867. Legal scholars argued that, being an ordinary federal statute rather than part of the Canadian Constitution, it had no impact on matters under provincial jurisdiction and little influence over inconsistent federal laws; therefore, the Bill provided inadequate protection for individuals' freedom from abuse by the state. There was some legitimacy to the latter claims. Although several human rights cases reached the Supreme Court of Canada, the Bill proved of little effect in guaranteeing the rights of individuals.

Lessons Learned

While experiences under the Bill of Rights were disappointing, the law made important contributions to Canada’s developing consciousness about how to protect human rights. The Bill introduced Canadian lawyers and judges to the discourse of rights, and sharpened Canadian awareness that protecting human rights and freedoms was something the government could do deliberately and by choice.

While experiences under the Bill of Rights were disappointing, the law made important contributions to Canada’s developing consciousness about how to protect human rights. The Bill introduced Canadian lawyers and judges to the discourse of rights, and sharpened Canadian awareness that protecting human rights and freedoms was something the government could do deliberately and by choice.

Perhaps more important was the awareness that the government could take action to advance human rights instead of simply arguing in technical terms over whether the provincial or the federal government had the authority over particular legislative topics. Canadians too were encouraged by the Bill’s deliberate effort to protect human rights. It was progressive, as Diefenbaker stated, that the “common Canadian” could use courts of law to hold the government to standards that protected civil rights.

Substantive vs Formal Laws

The distinction between “formal” and “substantive” laws is a critical prerequisite to understanding the advancements made in the Charter since the enactment of the Bill of Rights.

The distinction between “formal” and “substantive” laws is a critical prerequisite to understanding the advancements made in the Charter since the enactment of the Bill of Rights.

The Bill of Rights did not consider that identical treatment of all Canadians might have produced inequality. “Formal” laws in the Bill treated all members of one group identically, but did not treat all groups equally in relation to each other.

Building on the shortcomings of the Bill of Rights, Section 15 of the Charter is defined by “substantive” law, which provides equal protection and benefit of the law to every individual separately, regardless of group association.

Charter of Rights and Freedoms

Charting a Course

The very existence of the Bill of Rights, along with the litigation that evoked it, pointed to the importance of making changes to adequately protect human rights and freedoms appropriately. These modifications ultimately resulted in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982.

In substance, the Charter is built on the founding principles of the Bill. However, it also grew from the momentus changes between 1960 and 1980 that expanded the idea of what the definition of “human rights” included. The Charter differs substantially from the Bill in the breadth of what it covers and its ability to protect these liberties. While the Bill was vulnerable to amendments by the government with a simple majority vote, the Charter is entrenched in the Constitution. This means that alterations can only be made through complicated amending formulæ. For some changes, unanimous agreement of both the House of Commons and the Senate are required, while for others, a vote of seven out of the ten provinces (with a collective sum fifty percent of the Canadian population) is necessary. From the perspective of permanence, the Charter is better placed than the Bill to protect the rights of Canadians.

Coming of Age

In 1980, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, Canada’s 15th Prime Minister, began working on a charter of rights and freedoms. His design built upon the foundations laid down in Diefenbaker’s Bill of Rights. Between 1980 and 1982, Trudeau’s government solicited Canadians for feedback on what they wanted to include in a charter. From the thousands of submissions a special committee received, one hundred twenty-three recommendations were presented to the government — the final Charter contains over half of these. In addition to identifying and defending individual rights, the Charter aspires to promote national values as a counterbalance to regional or sectional loyalties.

In 1982, twenty-two years after the Bill was ratified, Trudeau introduced the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

"We must now establish the basic principles, the basic values and beliefs which hold us together as Canadians so that beyond our regional loyalties there is a way of life and a system of values which make us proud of the country that has given us freedom and such immeasurable joy." -Pierre Elliot Trudeau

Patriation

"… our truly Canadian Constitution is important to every citizen, containing as it does many of the long-established provisions that form the foundations of our society and of the laws under which we construct our affairs. …

"… our truly Canadian Constitution is important to every citizen, containing as it does many of the long-established provisions that form the foundations of our society and of the laws under which we construct our affairs. …

Most of the rights and freedoms we are enshrining in the Charter are not totally new and different. Indeed, Canadians have tended to take most of them for granted over the years. The difference is that now they will be guaranteed by our Constitution, and people will have the power to appeal to the courts…." -Pierre Elliot Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada

The Canada Act, 1982 “patriated” or “brought home” from Britain the Canadian Constitution, which had previously been part of the British North America Act (BNA Act). The Canada Act enabled the Canadian government to make amendments to the Constitution without having to petition the British parliament for consent, as had been required by the BNA Act. Patriating the Constitutiongranted Canada full sovereignty through the power to oversee its own constitution.

In order to meet the requirements of the Official Languages Act, the Constitution Act, 1982 and the Canada Act were written in both English and French. They were the first pieces of British legislation to be printed in two languages since the medieval era.

Entrenchment

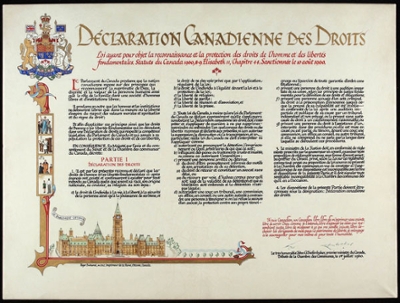

Many Canadians were initially apprehensive about particular rights in the Charter such as bilingualism and minority language education. The majority of provincial governments, including Saskatchewan, resisted the Charter, complaining that certain principles in it usurped provincial jurisdiction. Provinces pushed instead for revisions to the Bill of Rights, but Ottawa rejected this strategy, insisting that entrenching the Charter in the Constitution was the only way to guarantee rights protection. While the Bill could only render certain laws “inoperative” for a period of time if they contravened certain rights, entrenchment assured that any federal or provincial legislation inconsistent with the rights and freedoms guaranteed in the Charter would be judged invalid.

When discussions with the provinces came to an impasse, Trudeau threatened to bypass the Premiers altogether and enter into unilateral discussions with the British Crown. However, the Canadian Supreme Court declared that provincial consultation and consent was required for constitutional amendments. By including the Notwithstanding Clause, the Liberals managed to gain the support of most of the provinces for the Charter, but the Province of Québec refused to sign the document.

|

|

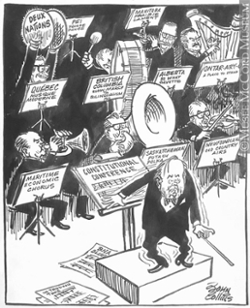

The Notwithstanding Clause

Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, (the Notwithstanding Clause or "override power") allows provincial legislatures to temporarily circumvent certain Charter-protected rights and freedoms in order to maintain current laws or pass new ones. The Clause only allows governments to override the Charter for renewable periods of five years. While the Clause can be applied to the Charter, it cannot be applied to any other part of the Canadian Constitution or to matters outside of provincial jurisdiction.

Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, (the Notwithstanding Clause or "override power") allows provincial legislatures to temporarily circumvent certain Charter-protected rights and freedoms in order to maintain current laws or pass new ones. The Clause only allows governments to override the Charter for renewable periods of five years. While the Clause can be applied to the Charter, it cannot be applied to any other part of the Canadian Constitution or to matters outside of provincial jurisdiction.

The Clause has been invoked on several occasions, with varying degrees of success. Québec, having refused to formally sanction the Charter, has used theNotwithstanding Clause a number of times to protect French language laws. In 2000, the Alberta government tried to apply the Clause to the Marriage Amendment Act in order to exclude same-sex unions. The Supreme Court of Canada struck down this attempt in a ruling that stated marriage law was a matter within Federal jurisdiction and therefore outside of the Alberta's purview.

Unfinished Business

In 1987 Prime Minister Brian Mulroney decided to address Québec’s concerns about the Charter by suggesting constitutional reforms through two separate accords. However, Mulroney was caught in the controversies generated by these documents.

In 1987 Prime Minister Brian Mulroney decided to address Québec’s concerns about the Charter by suggesting constitutional reforms through two separate accords. However, Mulroney was caught in the controversies generated by these documents.

The Meech Lake Constitutional Accord was a set of amendments meant to address Québec’s concerns that the Constitution Act, 1982 did not reflect their needs. “Meech Lake” as it came to be called, attempted to define Québec’s position in Canada and recognised the province as a “distinct society.” However, because of opposition to the Accord in several other provinces, the document did not pass.

After the Meech Lake Accord failed to be ratified in 1990, another series of negotiations took place that resulted in the Charlottetown Accord. This Accorddebated Québec’s position within Confederation, but this too was rejected because Canadians were unable to reach a national consensus.

La charte québecoise des droits et libertes de la personne

In 1975 Québec passed La charte québecoise des droits et libertes de la personne or the Québec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms — a bill written specifically by the Québec government for québecoise. Inspired by the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, La charte is an expression of Québec’s commitment to protecting the liberties of its citizens. Only the Canadian Constitution has precedence over La charte, with all of Québec’s other legislation being subject to it.

Looked at in the context of the creation of La charte, Québec’s opposition to the Charter in 1982 was clearly not a reflection of the province’s stance on human rights, as some critics argued. By including social and economic rights in addition to fundamental civil and political freedoms, La charte actually went even further than the Charter in that it covered a broader range of rights.

Canadian Human Rights Legislation

In Canada, two levels of government — Federal and Provincial/Territorial — ensure the protection of Canadian human rights legislation. Federally, the rights of the individual are safeguarded by the Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA) from other persons, organizations and the government. The CHRA (initiated in 1978) applies to matters that fall within federal jurisdiction. However, the CHRA can be amended by a simple majority vote in the federal House of Commons or even repealed.

In Canada, two levels of government — Federal and Provincial/Territorial — ensure the protection of Canadian human rights legislation. Federally, the rights of the individual are safeguarded by the Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA) from other persons, organizations and the government. The CHRA (initiated in 1978) applies to matters that fall within federal jurisdiction. However, the CHRA can be amended by a simple majority vote in the federal House of Commons or even repealed.

Every Canadian province and territory also has legislation protecting human rights. The example was set by Saskatchewan in 1947, when it became the first province to enact a provincial bill of rights. The Saskatchewan Bill of Rights was a precursor to Diefenbaker’s Canadian Bill of Rights and predated the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights by a year.

Human Rights Commissions are present in every province and territory, as well as in Ottawa. Although the Commissions differ in some respects, they all exist to investigate and mediate complaints, enforce compliance with legislation, and promote equality through public education and broad, proactive initiatives.

Successes and Challenges

Diefenbaker fashioned the Canadian Bill of Rights knowing that diversity was not just a matter of people's ethnicity or nationality.

His vision was that all members of society — including the disadvantaged, marginalized and disenfranchised — should be accorded basic human rights and fundamental freedoms. This thinking crossed over into the Federal Government's foreign policy.

|

|

Canada in the United Nations

The United Nations was formed in 1945 when 51 nations came together to ratify the United Nations Charter. The purpose of the UN is to maintain world peace and to promote human rights. Today the six official languages used by the UN — English, French, Arabic, Chinese, Spanish and Russian — reflect only part of the cultural diversity of the 193 countries that are its current members.

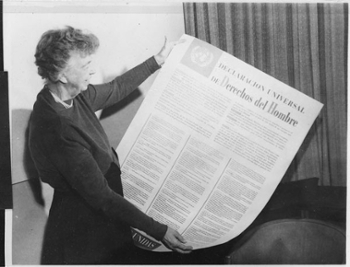

In 1948, the UN officially adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The Declaration affirms that the protection of international human rights is a global responsibility.

It was Canadian law professor and activist John Peters Humphrey, the Director of the Division of Human Rights within the United Nations Secretariat, who wrote the first draft of the UDHR.

"Civilization has progressed slowly, through centuries of persecution and tyranny, until, finally, the present Declaration has been drawn up. It is not the work of a few representatives in the Assembly...it is the achievement of generations of human beings." -Abdul Rahman Kayaly, Representative for Syria, United Nations, 1948

|

|

Objections to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

While the UDHR was, and remains, lauded as the first document to formalise international human rights principles, objections to it surfaced almost immediately. Some commented that it was largely a product of western thought and worldviews. Questions arose over how successfully the UDHR defined "universal" human rights, and whether it effectively encompassed the cultural mores and religious beliefs of a diverse world.

There were also uncertainties as to the usefulness of a declaration that was not enforceable against individual nation states committing human rights abuses against their own people. The Declaration, after all, was not a document created by a global government that could legislate international laws. For its part, Canada continues to play a central role in the work of the UN and continues to endorse and ratify worldwide human rights treaties.

“Throughout many centuries of political struggle to bring about human unity, the climax has now been reached with the preparation of the document in which 58 nations had expressed their common ideal and their… thoughts regarding fundamental human rights. The historic moment has come to proclaim the dignity of society, as well as legal standards which will lead him towards a new era of justice and culture.” -Jorge Carrera Andrade, Representative for Ecuador, United Nations, 1948

|

|

Keeping the Peace

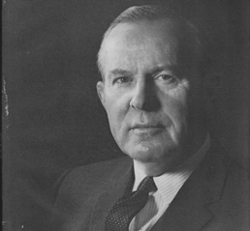

Peacekeeping around the world began with a Canadian: Lester B. Pearson, who became Canada’s 14th Prime Minister. In 1956, when Pearson was still the Secretary of State for External Affairs, he was instrumental in ending the Suez Crisis. Pearson worked to mobilize an impartial UN force to keep conflicting parties (Egypt and Israel/England/France) apart until a solution was brokered. He received a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts, but more importantly, Pearson inspired the idea of international peacekeeping. Since then, Canadians have served in more than 40 international peacekeeping operations.

Traditionally, peacekeeping forces exist to keep warring powers apart, but their roles have grown significantly. Canadian programmes now involve many civilians, and currently include the delivery of humanitarian aid, repatriation of refugees, and participation in community rebuilding and education. However, Canada does maintain active Canadian Forces in hostile areas and this has resulted in many casualties. Nevertheless, Canadians continue to volunteer for missions — evidence that we are willing to endanger ourselves in order to assist with achieving peace and securing rights and freedoms around the world.

|

|

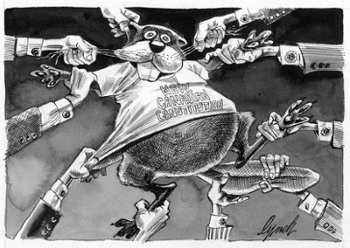

National Character

The roles that Canada plays today in promoting and protecting human rights has come from a long history of positive and negative experiences. From the time of theConstitution Act, 1867 through to the Charter in 1982, Canadians have had to come to terms with the fact that protecting human rights involves protecting the liberties of groups as well as individuals.

This has caused Canadian governments at both the federal and provincial/territorial levels to examine fundamental constitutional arrangements in comparison to the conventional ways that human rights cases have been handled in the past.

|

|

Looking Into the Future

Beyond our borders, other nations have looked to Canada to set the bar in the areas of human rights and freedoms, and civil liberties. They have come to expect and welcome Canada’s roles in the UN, NATO and similar organizations that further peace, justice and unity in a diverse world. These responsibilities have become a distinct part of our national character and something that Canadians take pride in.

However, we have not, as Canadians, finished looking at how our rights legislations, basic constitution, and foreign policies can be applied completely to the service of human rights. That search continues – and that too is distinctively Canadian.

|

|