An exhibited curated in partnership between the Diefenbaker Canada Centre and Whitecap Dakota First Nation.

The Dakota Oyate

Spirit of Alliance

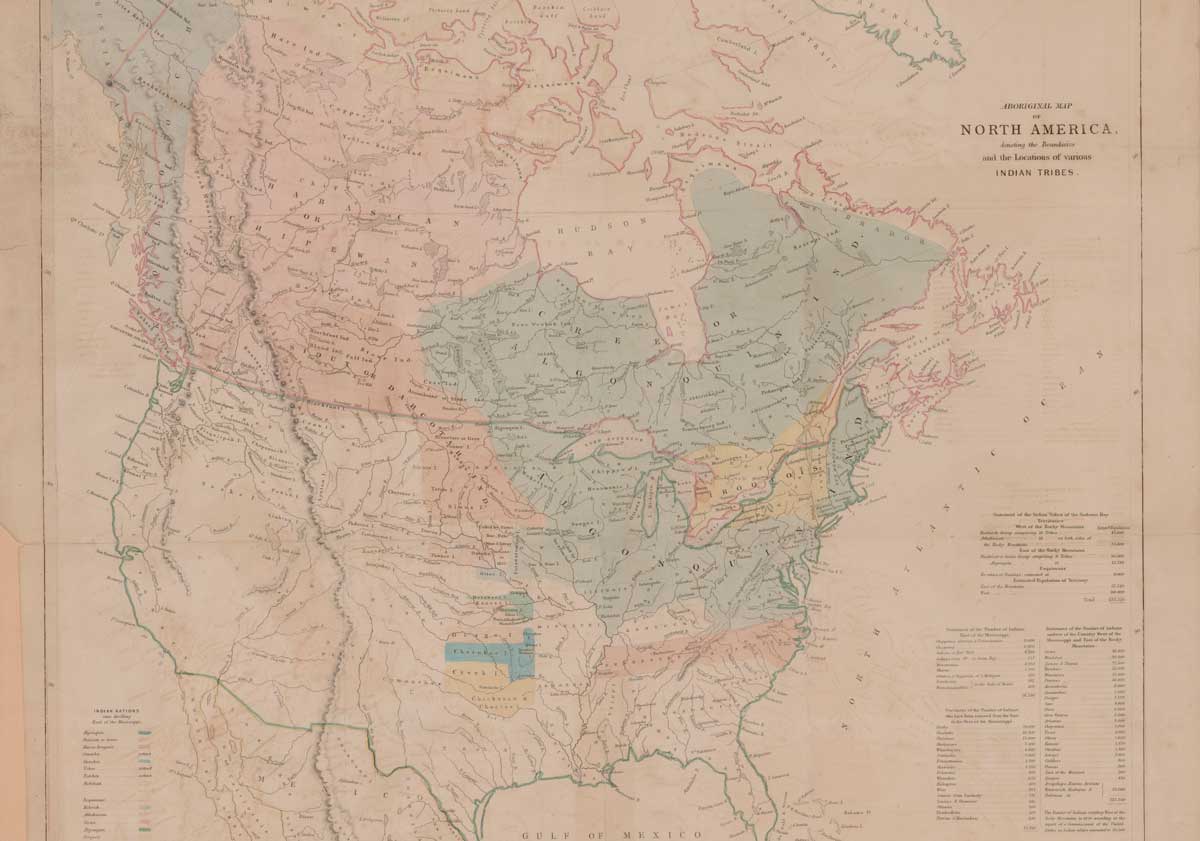

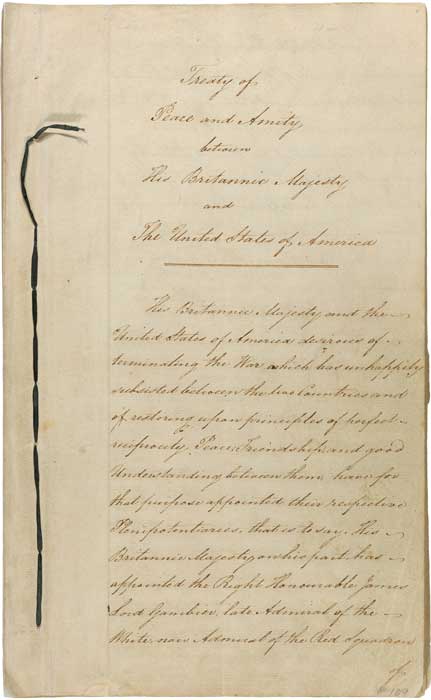

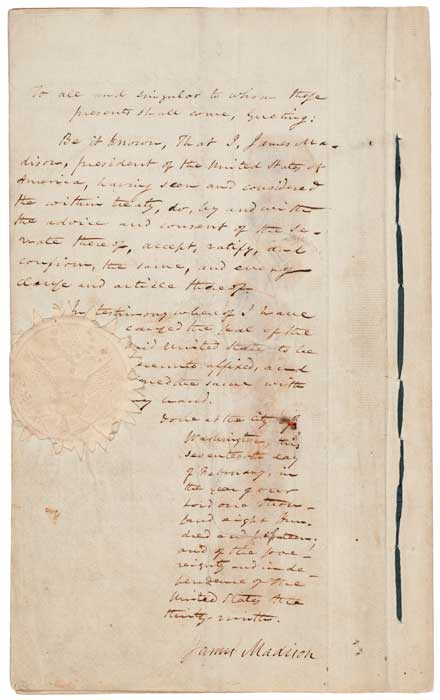

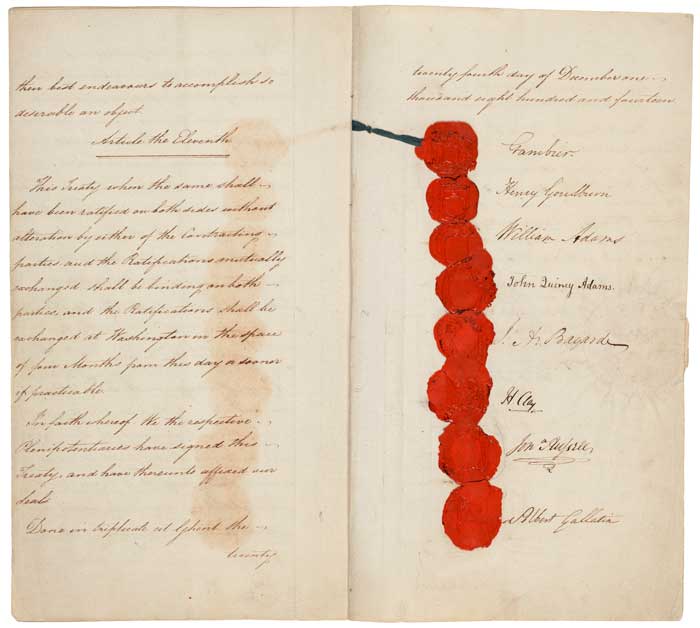

The word Dakota means “ally.” Alliance forms the basis of the Dakota’s long-standing relationship with the British Crown, recorded in wampum ceremonies in 1761 and a signed Treaty in 1787. The Dakota honoured their alliance with the British by joining them to fight against the Americans (or the “Big Knives,” as they were known) in 1763, 1776 and again in the War of 1812.

In January 1813, Colonel Robert Dickson held a series of councils with the Dakota and other Western First Nations. Distributing wampum belts, British flags, and medals, Dickson spoke on behalf of the British Crown and requested that these First Nations join the fight against the Americans, promising in turn, to protect Aboriginal lands.

“...With this [wampum] belt I call upon you to rouse up your young warriors and to join... the Red coats and your ancient bretheren the Canadians... in order to defend your and our country.... [the Americans] must be told in a voice of thunder that the object of war is to secure to the Indian Nations the boundaries of their territories...“ -Robert Dickson to Indian Tribes, 18 January 1813. McCord Museum of Canadian History, M640

Some of the most successful battles in the War of 1812 were fought and won by the British and Dakota on the Western Front. Following the defeat of the Americans at Prairie du Chien, Dakota Chief Little Crow spoke to British officials,

“I have sent the Americans from La Prairie du Chien... ...My Father, of my deeds, know that I and my Young Warriors have devoted our bodies to our Father the Red Head [Robert Dickson]...” -Enclosure in Sir George Prevost letter to Earl Henry Bathurst, 10 July 1814. Library and Archives Canada, RG 8 C Series Vol. 1219, Reel C-3526

A Promise Betrayed

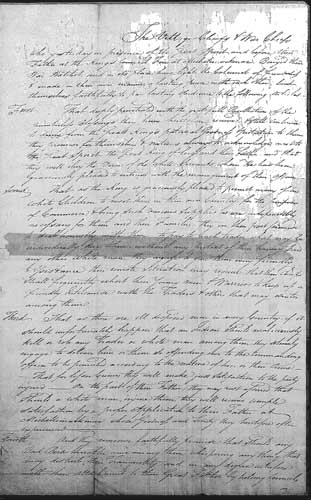

At a gathering at Drummond Island in 1816, Dakota and other First Nations leaders voiced their anger for the Crown’s failure to protect their traditional homelands. While Dakota Chief Wabasha was the first to speak out, he also promised to maintain the Dakota’s alliance with the Crown:

“Father I do not know what arrangements you made with the Big Knives [the Americans] when you buried the hatchet with them; I learnt that you had not forgotten us in the arrangement, but... I was told by the Big Knives, that it was not the case... ...yet we stretch our arms... and reach our English Fathers hand which we hold with a strong grasp, and never will let go as long as we live.” -Speech of Chief Wabasha, 29 June 1816. Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society, Historical Collections, 1890 Vol XVL

It was not only the First Nations who were angered at the betrayal. Many of the British officials who had fought alongside the Dakota were also outraged:

“Instead of flattering promises, which I was so lately instructed to make to them, being realized, the Whole Country is given up. A breach of faith is with them an utter abomination, and never forgotten.” -Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John McDonnell to Secretary Sir Augustus Foster, Michilimackinack, 15 May 1815. Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society, Historical Collections, 1890 Vol XVL

With the 49th parallel established as the border in 1818, the Dakota found themselves sharing their territory with their American enemies.

The Dakota eventually negotiated treaties with the United States, but in 1862, after enduring years of injustice, systematic treaty violations, and facing imminent starvation, many of the Dakota rose up. Hundreds decided to follow their trade routes into their northern hunting territories, seeking peaceful existence amongst their British allies.

Upon arrival at Fort Gary, Manitoba the Dakota presented their War of 1812 medals and quoted the Crown’s promises. However, the colonial administration failed to fully recognize their former allies.

In the early 1870s when Treaties One and Two were being negotiated, the Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba and the North West Territories met with Dakota leaders. He reported:

“When I asked their business with me, they declared that they and their forefathers had always been faithful to the Crown. ...They then placed on the ground a British flag and piled the medals on it, and went on to say that they came to ask for that protection and for a piece of land to live on.” -Sir Adams G. Archibald to Joseph Howe, December 27, 1871. Library and Archives Canada, RG 10 Series A, Vol 363, Reel C-9596

In 1874, North West Mounted Police Commissioner Sir George Arthur French expressed concern that the negotiations failed to include the Dakota and others. In reference to Cypress Hills, he stated:

“This country is the recognized hunting ground and war path of the Sioux, Assiniboines and Blackfeet tribes...” -G.A. French, Commissioner N.W.M. to Hon. Minister of Justice, 8 April 1975. National Archives of Canada, RG 18 Vol 5 File, 213-75

Ultimately excluded from the numbered treaties, the Dakota continued to protest on the basis that their traditional territory encompassed treaty areas. In spite of the long history of alliance with the British, Canadian officials took the stance that the Dakota were “American Indians.” |

|

Chief Whitecap’s Community

In 1879, Chief Whitecap and his people settled in their current location just south of present-day Saskatoon. Personal, trade and labour relationships connected the Whitecap Dakota to their nearby communities. In August 1882, Chief Whitecap counseled John Lake on the location for a new temperance colony that would become the City of Saskatoon. Today, Chief Whitecap is recognized as one of the founders of the city.

Continuing the Military Alliance

Over the decades that passed, the Whitecap Dakota maintained their allegiance to the Crown. This was particularly evident during the Second World War, when seven members of the small Whitecap community were part of the Canadian forces, with three men serving overseas. The community also made regular donations to the war effort.

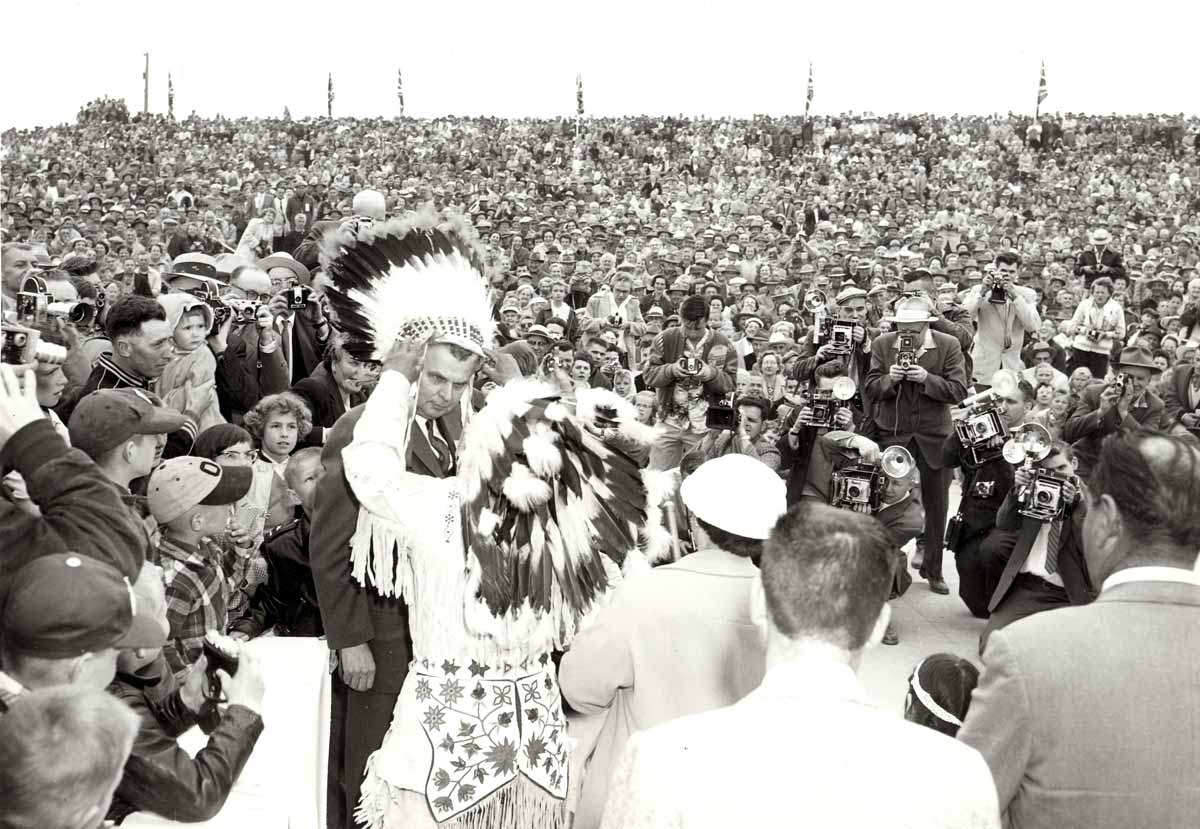

An Honour Bestowed

In 1959, Whitecap Dakota First Nation Chief Little Crow granted Prime Minister John Diefenbaker the honourary name Walking Buffalo at the inauguration of the construction of the Gardiner Dam near Outlook, SK. During his speech, Diefenbaker stated:

In 1959, Whitecap Dakota First Nation Chief Little Crow granted Prime Minister John Diefenbaker the honourary name Walking Buffalo at the inauguration of the construction of the Gardiner Dam near Outlook, SK. During his speech, Diefenbaker stated:

“The Sioux [Dakota] history has been one of honour to your race and great distinction to this country.” -John Diefenbaker, 1959 May 27. University of Saskatchewan Special Collections, Diefenbaker Fonds, XI_B_723

In 2012, the Government of Canada formally recognized the Dakota, along with other First Nations allies in the War of 1812, as key to the victory that firmly established Canada as a distinct country in North America.

The Whitecap Dakota Today