Introduction

LGBTQ2S+ people have always existed on the prairies: Two-Spirit (niizh manidoowag) people have lived here long before European settlers arrived, with numerous accounts of First Nations who had same-sex partners or did not conform to traditional gender roles. Unfortunately, with the arrival of settlers, colonial homophobia and gender discrimination were introduced to the prairies and are rampant still today, even after Pierre Trudeau’s government partially decriminalized homosexuality in 1969.

This exhibit explores the activism that took place in Saskatchewan from the late 1960s through the summer of 2020. Journey through the stories of lesbian and gay activists and groups of the 1960-1980s that fought for their basic human rights and the ability to celebrate their sexuality and gender identity openly and freely in annual Pride festivals, as well as the continued activism and celebrations of queer groups from 1990-2020.

Accompanied by excerpts from interviews with individuals in the Saskatchewan queer community, experience the decades of hard work and dedication of the queer community that brought Pride to being the major summer festival it is today.

LGBTQ2S+

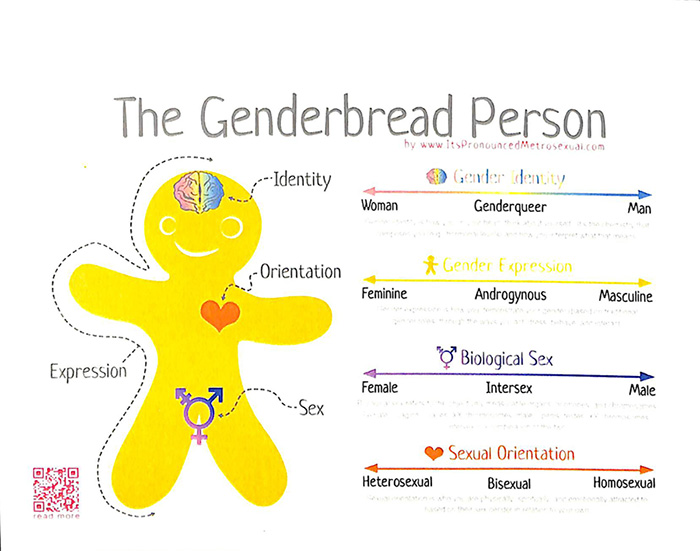

LGBTQ2S+ stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Two-Spirit, and other gender identities. This acronym is used throughout this exhibit as an inclusive way to address the larger queer community when appropriate, but can be found in many variations throughout mainstream media and academic works.

Two-Spirit

In 1990, the term Two-Spirit (niizh manidoowag) was introduced in an academic context that allowed Indigenous LGBTQ2S+ individuals to reject the English terms that imposed Western views.

Reclaiming the term ‘queer’

Throughout the exhibit different identity terms are used depending on the context. During the 1960s and 1970s, individuals preferred to use the terms gay and lesbian instead of queer, as it was often used as a discriminatory and hateful term. It wasn’t until the late 1980s that queer began appearing in academic circles in a positive context and was increasingly used by activists to describe themselves with pride. As time passes and queer is more regularly used in mainstream media, it appears to be a generational choice, where millennials and Gen Zers use the term more naturally than older generations. To reflect this evolution, the term is used increasingly throughout the exhibit as it moves chronologically through history.

While the use of queer becomes more commonplace in mainstream media, it is important to note that many are still uncomfortable with using this term to describe themselves and others due to its historical use as a hate term. As such, it is always best to ask individuals which term they prefer to use instead of ascribing one to them.

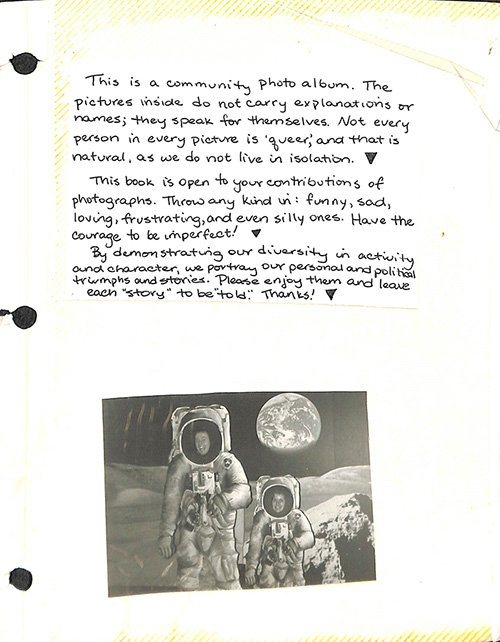

A front page from a photo album, the handwritten text reads:

"This is a community photo album. The pictures inside do not carry explanations or names; they speak for themselves. Not every person in every picture is ’queer’ and that is natural, as we do not live in isolation. This book is open to your contributions of photographs. Throw any kind in: funny, sad, loving, frustrating, and even silly ones. Have the courage to be imperfect! By demonstrating our diversity in activity and character, we portray our personal and political triumphs and stories. Please enjoy them and leave each ‘story’ to be ‘told.’ Thanks!”

-The writer of this caption is unknown.

Special Acknowledgments

This exhibit would not be possible without the support of the USSU Pride Centre and the work of Valerie Korinek, author of ‘Prairie Fairies: A History of Queer Communities and People in Western Canada, 1930-1985'. Valerie is herself an integral part of LGBTQ2S+ history in Saskatchewan and has dedicated decades of her academic career to studying queer history.

The content of this exhibit reflects only a small portion of the research regarding queer history and the development of Pride celebrations in Canada, with a specific focus on Saskatchewan.

This exhibit was created with the support of funding through the Government of Canada Young Canada Works and Canada Summer Jobs.

Community Organizations

Community organizations are an essential part of organizing activism and Pride events. For many they serve as a first point of contact with the queer community. They allow members of the community to meet each other, socialize in a space that accepts them for who they are, and organize activism. Without these organizations to help people come together, it is difficult to imagine that any sort of official Pride celebration would have ever been possible.

Organizations of the 1970s (Saskatoon)

“...in Saskatoon [1971] the activist group was formed first, making it the community leader, and, in many ways, the activists used the social club fundraisers to help support their work.”

-Valerie Korinek, Prairie Fairies: a history of queer communities and people in western Canada, 1930-1985.

After the partial decriminalization of homosexuality in Canada in 1969 and inspired by developments in the United States, gay and lesbian people began to reach out and find each other in order to start forming support groups and community organizations.

Saskatoon Gay Action

In 1971 gay activists Gens Hellquist and Dan Nahlbach placed an ad in the Georgia Straight, an alternative newspaper based in Vancouver that sometimes-discussed gay rights issues. The ad was only one line asking interested readers to get in touch. A handful of men and one woman responded to the ad, and in 1971 two gay organizations formed in Saskatoon: Saskatoon Gay Action (SGA) and The Gay Students Alliance. While it is unclear what happened to the Gay Students Alliance, SGA remained an activist organization in Saskatoon for the next few years.

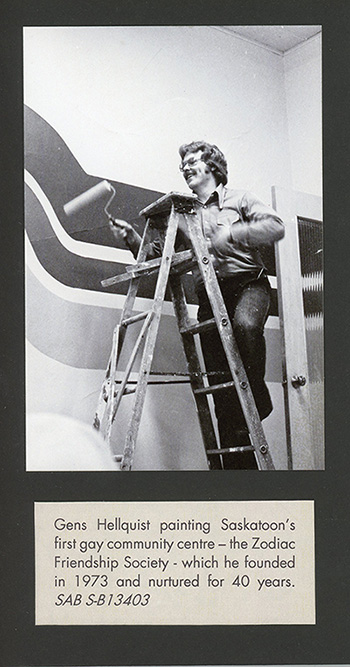

The Zodiac Friendship Society

While SGA’s activist work was important, members of the LGBTQ2S+ community also wanted a space to socialize. In 1972, a second organization called the Zodiac Friendship Society (ZFS) was created. The ZFS oversaw the Gemini Club, a social club where they would host social events and fundraisers like dances. The SGA would often use funds raised by the Gemini Club for their activist work.

“Similar to other prairie cities, they purposefully chose a slightly playful, coded name that would not trigger concerns or cause cautious members to avoid the group for fear of exposure.”

-Valerie Korinek, Prairie Fairies: a history of queer communities and people in western Canada, 1930-1985.

The Gay Community Centre of Saskatoon

The Gay Community Centre of Saskatoon

The partnership between SGA and the ZFS continued until 1975, when the two organizations officially combined to create the Gay Community Centre of Saskatoon (GCCS). The GCCS continued hosting social events and organizing activist efforts while also providing education, counseling, and aid services to its members.

Organizations of the 1970s (Regina and Wider Saskatchewan)

The Atropos Friendship Society

Meanwhile in Regina, the Atropos Friendship Society, modeled after the Zodiac Friendship Society, was formed in 1972. The Atropos Society ran a social club called the Odyssey as well as a phone line for those seeking support or interested in becoming involved.

Meanwhile in Regina, the Atropos Friendship Society, modeled after the Zodiac Friendship Society, was formed in 1972. The Atropos Society ran a social club called the Odyssey as well as a phone line for those seeking support or interested in becoming involved.

In an era where gay and lesbian activism was just getting started and many people were still “closeted” from their co-workers, friends, and family, discretion was a huge concern for those looking to get involved in community organizations. For that reason, Regina’s Odyssey Club was a privately-owned house. The windows were boarded up and the house was not marked with any signs indicating what it was. Those attending social events entered through the back door. Interested members often had to meet privately with an existing member who would confirm their identity as lesbian or gay before telling them the location of the club.

“When I first came out it felt like it was an underground thing. Like, going to the gay club in Regina you had to have a membership, you had to have your ID, and the door was well-manned. It just felt like this one little spot downtown that nobody really knew about. Like, there wasn’t a visible sign or anything like that. So it almost felt like this little, secret part of society that I was a part of.”

-Melody Wood, Saskatchewan Indigenous Cultural Centre

In 1977 the Atropos Friendship Society was renamed twice, first to the Gay Community of Regina, and finally to the Gay and Lesbian Community of Regina. This social group still exists today, making it the longest running gay community organization in Canada.

The Saskatchewan Gay Coalition

In 1978 the Saskatchewan Gay Coalition (SGC) was formed for the purpose of doing outreach to the rural communities of Saskatchewan. Activist Doug Wilson traveled around Saskatchewan’s rural communities to connect with LGBTQ2S+ people living there. The SGC helped people connect with Saskatchewan’s LGBTQ2S+ community and keep informed about events and issues.

“Wilson’s official reason for the coalition building was based on a genuine concern to help rural gay people access support and social networks, from which, he believed, political action would follow.”

-Valerie Korinek, Prairie Fairies: a history of queer communities and people in western Canada, 1930-1985.

Early Indigenous Community Organizations

Indigenous activists were present from the beginning of LGBTQ2S+ community organizations in Saskatchewan. In 1978, the SGC community newsletter Gay Saskatchewan put out a call for a gay Indigenous group (the term Two-Spirit had not yet come into mainstream use). In 1979, the GCCS held a meeting for Indigenous lesbians and gay men. The last mention of the group was of a dinner party they held in the GCCS, which included traditional music and dancing. Unfortunately, not much more published information currently exists on early Indigenous activists in Saskatchewan. They were certainly out there, but their history has yet to be documented in academia.

"What is thought to be the first the first group for Native gays and lesbians in Canada also appeared in this period, in Saskatoon. Founded in the late 1970s, the Gay Native Group was listed in Gay Saskatchewan, the newsletter of the Saskatchewan Gay Coalition, as late as October 1979, but disappeared shortly thereafter . . . The organizations and meeting places of the broader gay, lesbian, and bisexual communities were almost exclusively populated by white people of European descent who had little awareness of or contact with Aboriginal peoples."

-Tom Warner, Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada.

Organizations in the 1980s

Gay and Lesbian Support Services and the End of the Gay Community Centre of Saskatoon

In Saskatoon, activist Gens Hellquist was becoming concerned that the GCCS was too focused on socializing. As a reaction, he formed Gay and Lesbian Support Services (GLSS) in 1980. GLSS provided counseling, a phone line, and self-help groups.

Due to lack of funding, burnout, and interpersonal conflicts amongst directors, the GCCS closed permanently in 1982.

GLSS continued to run until 1987, when it permanently ceased all activity due to lack of volunteers.

Lesbian Organizations

Elsewhere in the late 1970s and early 1980s, lesbians began to create their own spaces and organizations. Many lesbians realized that prairie feminist organizations weren’t welcoming to them and existing gay organizations were too male-centric. So, the Lavender Social Club was formed as a specifically lesbian group in Regina in the early 1980s, with the Lesbian Association of Southern Saskatchewan founded around the same time. These organizations held women’s only events and often provided support to lesbian mothers engaged in custody battles. Unfortunately, due to a lack of resources and volunteers, these organizations no longer exist.

Today's Community Organizations

OUTSaskatoon

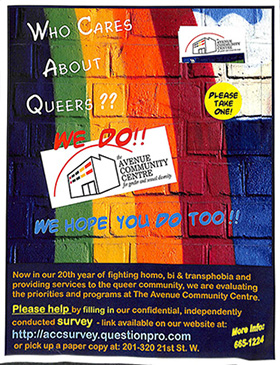

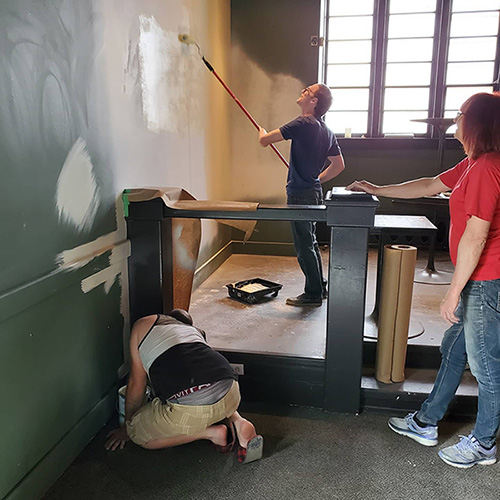

Apparently not disheartened by the GLSS closing, Gens Hellquist teamed up with Dr. Sheri McConnell to form Gay and Lesbian Health Services in Saskatoon in 1991. In 2005 the organization changed its name to The Avenue Community Centre. Finally, in 2015, the Avenue Community Centre became OUTSaskatoon.

Today OUTSaskatoon is the most prominent queer community organization in Saskatoon. It hosts a plethora of social events and groups catered to queer youth, LGBTQ2S+ elderly people, Two-Spirit people, and people of all gender identities. OUTSaskatoon also provides a drop-in social space, counseling, and other support services. In 2017 OUTSaskatoon opened Pride Home, a communal living space for queer youth who are homeless. In summer 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, OUTSaskatoon started offering their counseling services over the phone, and holding educational workshops online.

|

|

The Gay and Lesbian Community of Regina

The Gay and Lesbian Community of Regina

The Gay and Lesbian Community of Regina continues to run until this day. The organization now owns and operates Q Lounge and Night Club, providing meeting spaces for members of the queer community to socialize and get support. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the GLCR ran into financial trouble and started a GoFundMe campaign to keep their club operating. 22 days after beginning the campaign, the GLCR reached its goal of $25,000 in donations.

TransSask Support Services

TransSask Support Services provides support to gender diverse people across the province. They provide information about counseling services and medical transitioning to those who need it.

The USSU Pride Centre and UR Pride

The University of Saskatchewan and the University of Regina each have their own campus-based queer organizations, The USSU Pride Centre and UR Pride.

UR Pride runs a variety of programs, some of which are for the general community and not necessarily just students. Mental health support services, support groups for people of various sexual orientations and gender identities, and a student lounge are among the many things this group organizes.

The USSU Pride Centre provides a drop-in safe space for students and hosts various meetups and social nights, such as Queer Women’s Night, Gender Coup D’état, and Gaymer Night.

|

|

Human Rights

The road to official Pride celebrations was a long and difficult one. Even though homosexuality was partially decriminalized in 1969, gay and lesbian people’s basic human rights were not protected by law. Not only were same-sex couples barred from getting married or adopting children, it was also legal for a person to be fired for their sexuality, and homophobia was not legally considered hate speech. There were no legal protections against discrimination for queer people, so city councils openly rejected gay and lesbian activists’ requests to host Pride festivals. Before Pride could happen, gay and lesbian people had to be granted their human rights.

Activism and Protests in the 1970s

When Saskatoon Gay Action (SGA) was founded in 1971, one of its primary goals as an organization was to lobby the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission for equal rights under the law and protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation.

In August of 1973, SGA activists presented a brief to the provincial government that called for an amendment to the Saskatchewan Human Rights Code to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. The provincial government’s reaction to the brief was positive, but they did not actually take any action to change the code at that time. It would be twenty years before this legislation was passed.

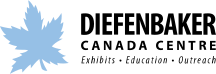

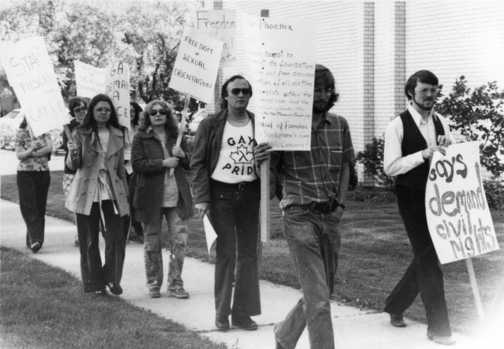

The First Protest

The First Protest

On June 10th, 1975, Saskatchewan’s first public demonstration took place. A handful of Saskatoon activists gathered outside the StarPhoenix office to protest the paper’s denial to print an advertisement submitted by the Gay Community Centre of Saskatoon (GCCS).

Doug Wilson

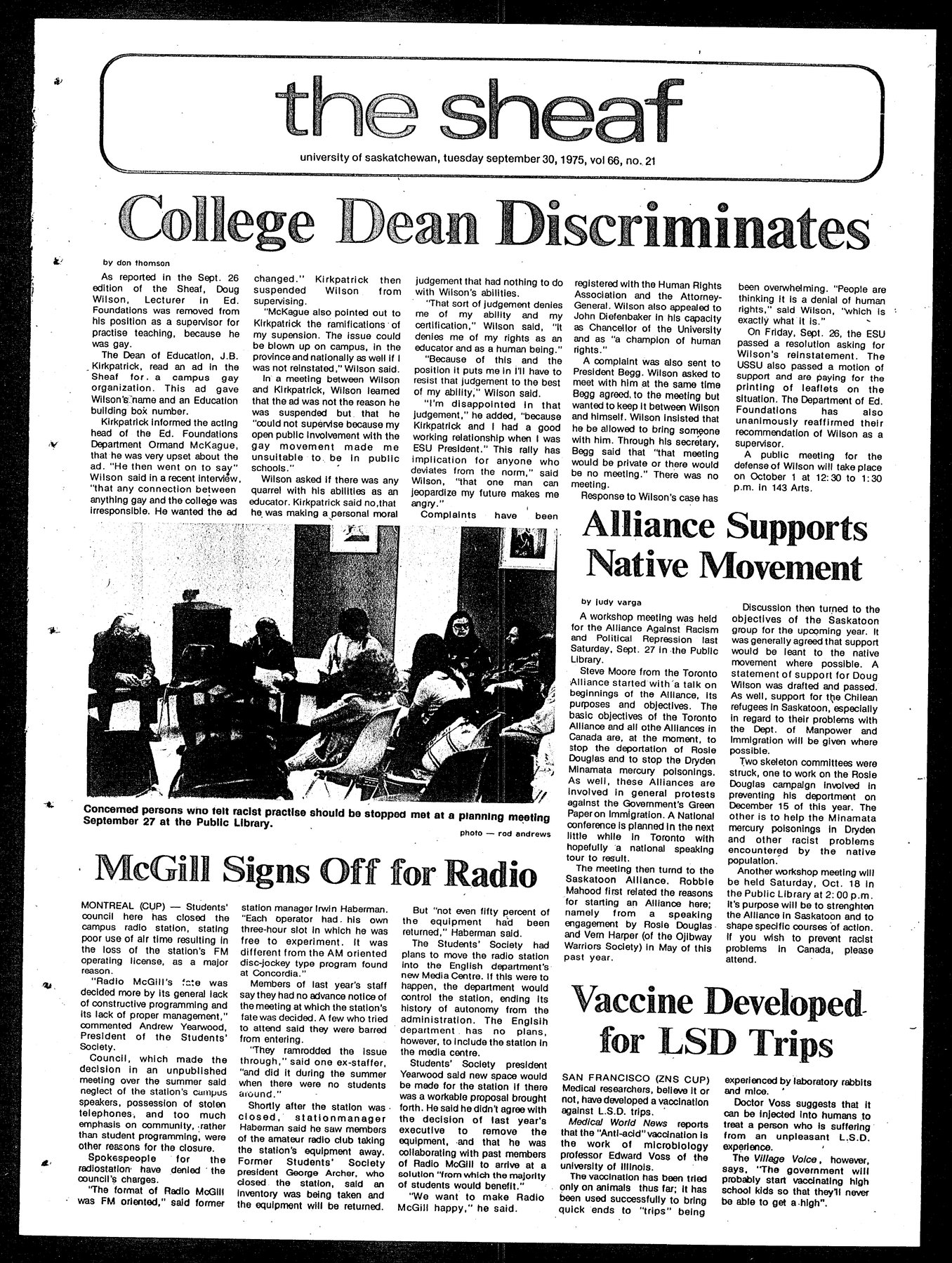

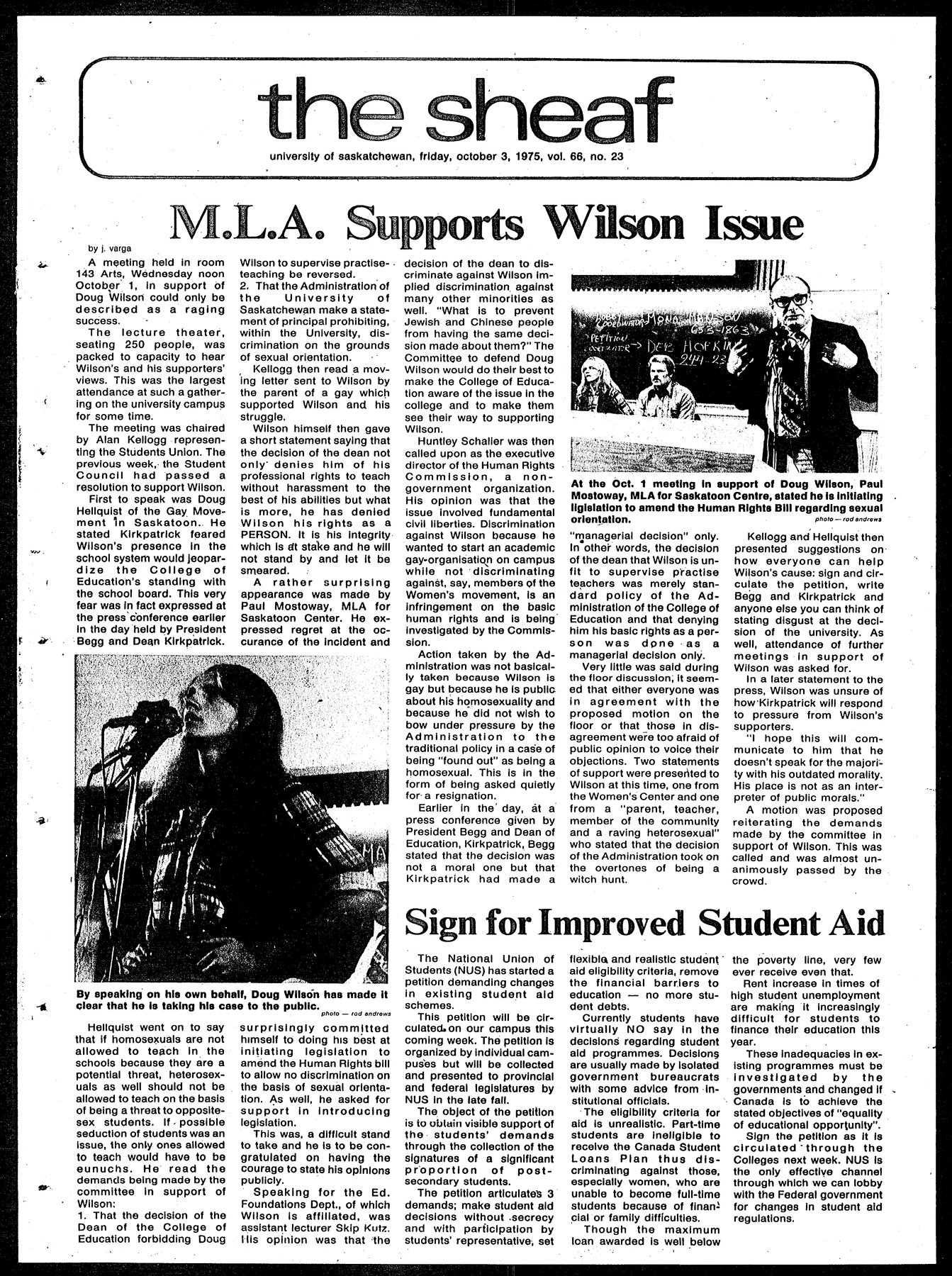

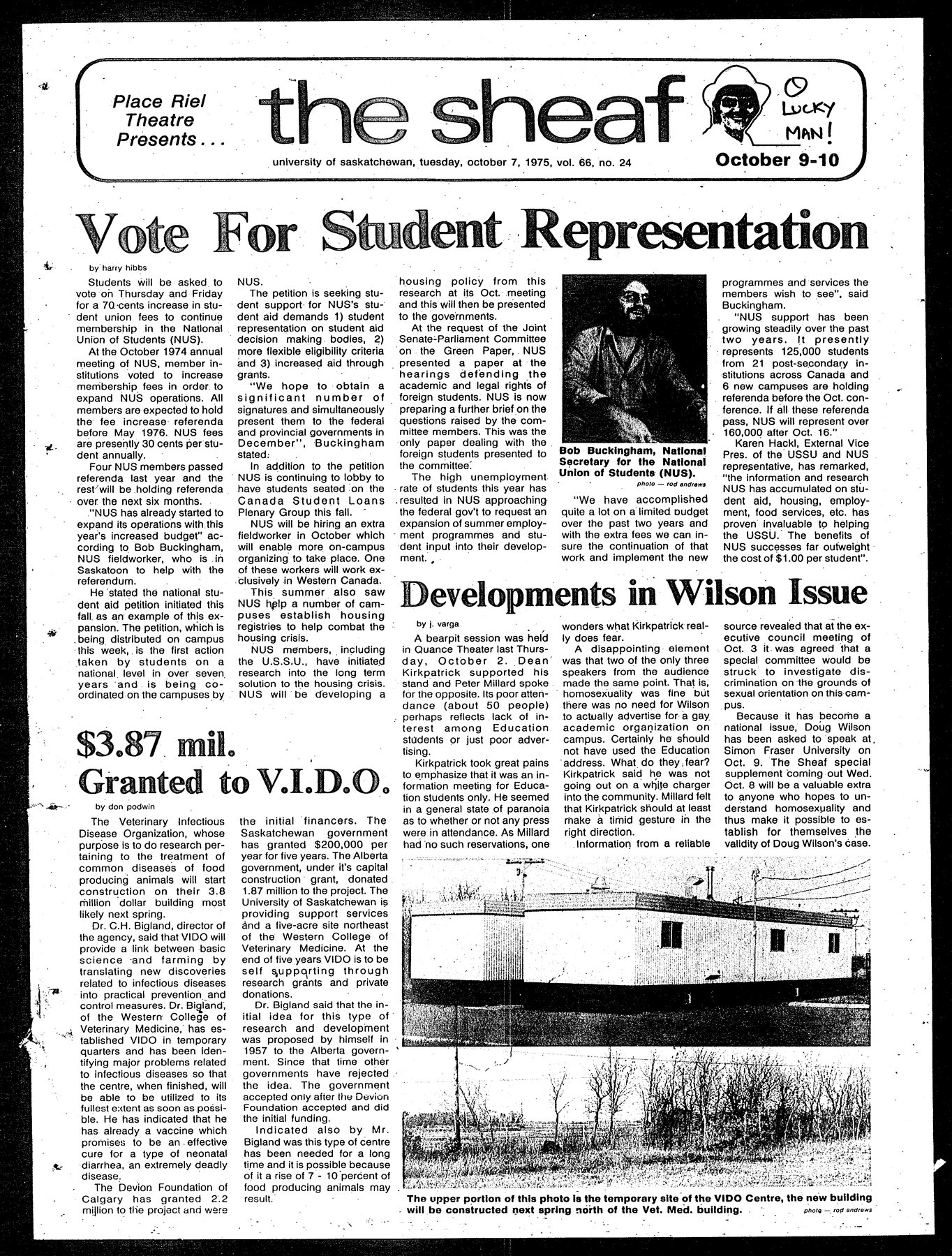

In September 1975, issues of gay rights suddenly rocketed into mainstream consciousness because of activist Doug Wilson. Wilson, a graduate student at the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Education, was suspended from his position supervising student teachers after attempting to start a queer student organization. The Dean of Education and the university’s president decided that Wilson was unfit to work in schools due to his sexuality. Furthermore, the university worried that having an openly gay man in the College of Education would hurt their relationship with Saskatoon’s school boards. The Dean and the President probably expected Wilson to quietly resign, but instead he took his case public.

In September 1975, issues of gay rights suddenly rocketed into mainstream consciousness because of activist Doug Wilson. Wilson, a graduate student at the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Education, was suspended from his position supervising student teachers after attempting to start a queer student organization. The Dean of Education and the university’s president decided that Wilson was unfit to work in schools due to his sexuality. Furthermore, the university worried that having an openly gay man in the College of Education would hurt their relationship with Saskatoon’s school boards. The Dean and the President probably expected Wilson to quietly resign, but instead he took his case public.

The Sheaf published multiple articles on the topic, which sparked outrage among many university students and professors. The University of Saskatchewan Student Union (USSU) and the Education Student Union (ESU) publicly supported Wilson and his case went national, reported by news outlets across Canada. Wilson even appeared on televised interviews with CBC and CTV.

“In most respects, the most liberating development throughout the Wilson case had been the public discussion and debate. The Wilson affair created a public forum to discuss homosexuality which was previously unheard of in Saskatchewan. As the semester progressed and peopled were offered more information about homosexuality, it because clear that many on campus had moved from ignorance to acceptance…Members of the campus shared the progression of their thoughts on the matter, and it demonstrated that, if nothing else, the Wilson case had educated people.”

-Valerie Korinek, ‘The most openly gay person for at least a thousand miles’: Doug Wilson and the Politicization of a Province, 1975-83.

Read The Sheaf articles on the Wilson case below. Click on the images below and enlarge by clicking "View in new tab".

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Activists in Saskatoon came together to form a ‘Committee to Defend Doug Wilson’, which worked to raise money to cover some of his legal fees. Wilson appealed his case to the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission (SHRC), who agreed to take the case. For the first time in Canada a formal investigation dealing with discrimination based on sexual orientation was launched. The SHRC tried to press charges for discrimination based on sex. However, Wilson did not lose his position because he was a man, and sexual orientation was not legally protected from discrimination, so in the end there was no legal foundation for Wilson’s case.

While Wilson may have lost the court battle, his case and its publicity made significant progress in terms of gay rights visibility in Saskatchewan and across Canada. The Wilson case brought national attention to the reality that gay and lesbian people had no legal protection, and so garnered sympathy for these activists’ cause. Because of his sexuality Doug Wilson was never able to become a teacher, but he did go on to become a prominent gay activist.

Protests of 1977

Protests of 1977

On March 12th, 1977, 150 activists came together outside the legislature in Regina to protest the government’s inaction and unwillingness to amend the Human Rights Code to protect the rights for homosexuals.

“The march was held in Regina for a couple of reasons. First, as the provincial capital, mobilizing in front of the legislature was symbolically important. It was also a central location that could (and obviously did) draw activists from Saskatoon, Winnipeg, and Edmonton.”

-Valerie Korinek, Prairie Fairies: a history of queer communities and people in western Canada, 1930-1985.

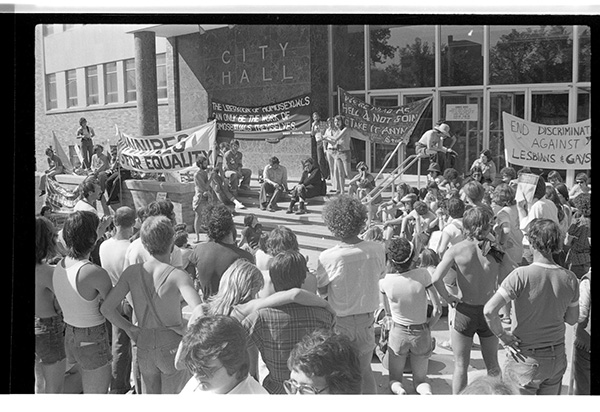

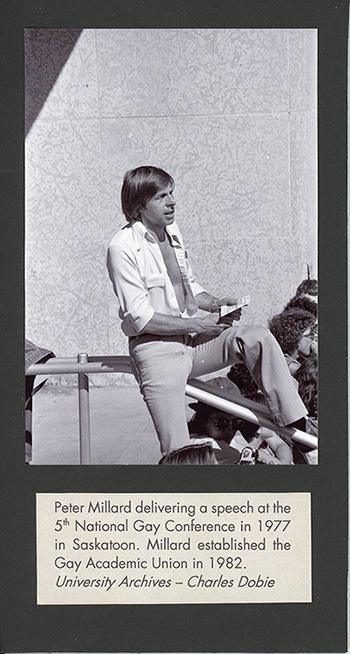

That summer, Saskatoon hosted the fifth annual National Gay Rights conference. The conference included public speakers at the University of Saskatchewan and social events including film screenings and a dance. The main event of the conference was a protest march. On July 1st, 300 protestors from all over Canada marched from Kiwanis Park to city hall calling for human rights for gay and lesbian people.

Gay Rights Now!

In the summer of 1978, gay and lesbian rights protesting spread to a smaller Saskatchewan community. Anita Bryant, an anti-gay and anti-feminist advocate, toured across the United States and Canada to speak about her anti-gay beliefs in a campaign she called “Save Our Children.” Bryant’s Canadian tour included a stop in Moose Jaw, and on the day of her visit gay rights activists, allies, and feminists from across the province gathered to protest her campaign. In Moose Jaw’s first ever protest for gay and lesbian issues and rights, 250 protestors marched through Moose Jaw’s Main Street chanting “women, workers, gays unite – same struggle same fight! Gay rights now!”

Activism in the 1980s

The 1970s saw positive progress in terms of gay and lesbian activism and visibility, but this progress mostly halted in the 1980s. Saskatchewan’s population was not very large, and many of the same people were continuously organizing and leading activist work. Eventually, some of Saskatchewan gay and lesbian activism’s key leaders had burned out or moved elsewhere. Additionally, in the 1982 provincial election the NDP government of the 1970s was replaced by Grant Devine’s Progressive Conservative government. While the NDP government was willing to listen to gay and lesbian activists, Devine was publicly homophobic and openly disapproved of granting human rights to gay and lesbian people.

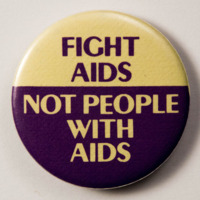

The most devastating thing to happen to the gay community as a whole in the 1980s, however, was the HIV and AIDS crisis. The crisis justifiably put human rights activism on hold in favour of activism geared towards supporting people with AIDS, raising awareness, combating misinformation, and developing safe-sex education programs.

Activism in the 1990s

As treatments for HIV and AIDS were developed activism once again turned its focus towards human rights advocacy.

Electoral Promises

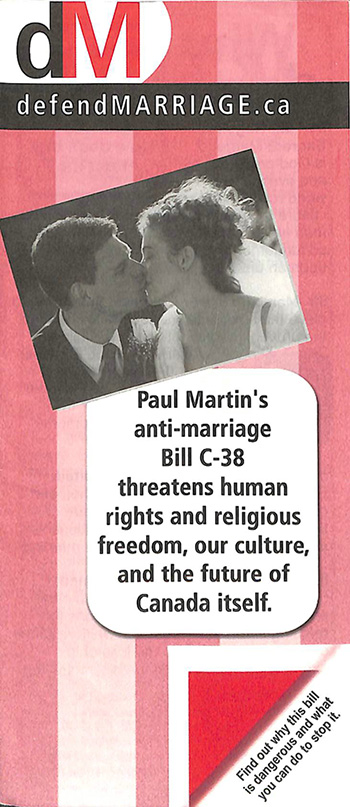

During the 1991 provincial election, the question of gay rights became a key issue when Roy Romanow of the NDP party promised to grant gay people their rights if he were elected. This statement sparked a massive counter-campaign from the PC party, who promised to protect “family values” if they were re-elected. The PC party even circulated campaign pamphlets that claimed gay people would get “special rights” if the NDP were elected. The NDP did end up winning the election, but the backlash they received for promising gay rights was so strong that they were reluctant to amend the human rights charter.

Bill 38

Bill 38

On June 22 of 1993, after twenty long years of activism, Bill 38 – a bill protecting human rights on the basis of sexual orientation – was passed by the provincial NDP government. Saskatchewan became the 7th province to amend its charter of rights to protect the human rights of the LGBTQ2S+ community.

“One thing that I want to say is that I am definitely aware that queer people have been fighting for our rights for a very, very long time. So if at any point it felt like what we have done is created something new -- never. I am happy for the people that came before me to have a space where I feel like I can continue something going forward. Because I think, at the end of the day for all people who do this kind of work, it’s just to make it easier for future generations.”

-Melody Wood, Saskatchewan Indigenous Cultural Centre.

Marriage Rights

Although it was made illegal to discriminate against people based on their sexual orientation, same-sex couples were still not allowed to get married or adopt children. Eventually, Justice Donna Wilson ruled that not allowing same-sex couples to be married violated their rights, and on November 5th, 2004, Saskatchewan became the 7th province to legalize same-sex marriage. The very next day Erin Scriven and Lisa Stumborg became the first same-sex couple to be married in Saskatchewan. They were wed at St. Thomas United Church in Saskatoon.

Even though same-sex marriage was legal, finding someone to officiate the ceremony was another matter entirely. Officiants still had the right to refuse to marry same-sex couples if they wished. The Mennonite Church of Canada didn’t marry any same-sex couples until 2015 when Craig Friesen and Matt Wiens were married on December 31st in Osler, Saskatchewan.

Transgender and Non-binary Rights

The Right to Gender Expression

While the gay and lesbian communities have been in the public consciousness for a while, the transgender and non-binary communities, while they have always existed, have only broken into the mainstream recently.

While sexual orientation was added to the human rights code in 1993, a person’s right to express their gender identity was not protected at this time. Previously, only biological sex was acknowledged on the charter. It wasn’t until 2017 that amendments were made to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms to officially protect Canadians’ right to express their gender identity.

Transgender Rights and Visibility

The term transgender was coined back in 1965, and transgender people were prominent participants in the Stonewall riots of 1969. In the 1990s the transgender pride and rights movement began gaining more steam. Transgender people began seeking more visibility and acceptance, and the letter ‘T’ began being added to acronyms for the LGBTQ2S+ community.

One aspect of increased transgender visibility is acknowledging the wrongs that have been acted upon the transgender community. In 1999, the first Transgender Day of Remembrance was founded by Gwendolyn Ann Smith to memorialize Rita Hester, a trans woman who had been murdered the year before. Transgender Day of Remembrance is observed internationally on November 20th to acknowledge all the transgender people who have been lost to transphobic violence. The USSU Pride Centre, along with many queer organizations throughout Saskatchewan, annually holds a Transgender Day of Remembrance vigil.

Transgender people have been seeing increased legal recognition and access to materials they need to transition, but there are still many barriers for them. In Saskatchewan there is limited access to medical transitioning procedures, and many people need to travel outside of the province in order to fully transition. Surgeries are covered by healthcare, but travel costs are not, making transitioning inaccessible to many who cannot afford the travel bills. In a 2015 study of transgender healthcare in Saskatchewan, many of the participants said they had felt unsafe or judged around some healthcare providers.

Non-binary Rights and Visibility

The visibility and acceptance of non-binary gender identities has made leaps and bounds in recent years. The term “genderqueer” was coined in 1995 to describe people whose gender identity wasn’t fully male or female, but the term non-binary has since become the new umbrella term for anyone whose gender identity does not fit with the male-female gender binary.

|

|

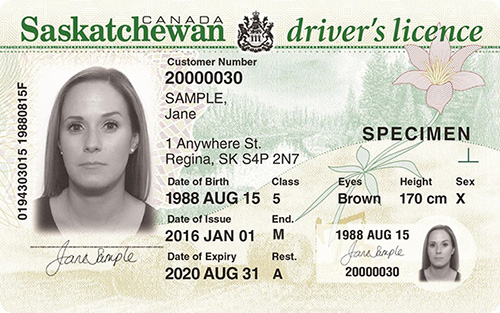

In 2017, after ruling to protect the right to gender expression, the federal government ruled that passports could be made gender neutral. Anyone that does not fit into the gender binary can now opt to have the gender marker on their passport changed to X rather than M/F.

In 2017, after ruling to protect the right to gender expression, the federal government ruled that passports could be made gender neutral. Anyone that does not fit into the gender binary can now opt to have the gender marker on their passport changed to X rather than M/F.

As of 2018, after the request of two Saskatchewan minors, gender markers can be legally removed from Saskatchewan birth certificates. In 2019, following the government of Saskatchewan’s decision to allow non-gendered birth certificates, SGI updated their policy to allow gender markers on driver’s licenses to be changed to X -- no questions asked.

Although there has been undeniable progress in queer visibility and acceptance, transgender and non-binary people are still fighting for legal recognition, access to medical procedures, and increasing visibility through flag-raisings and a presence in Pride parades and activities.

HIV & AIDS

Activism was going strong in the 1970s, but the HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) and AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) crisis brought things to a halt. So serious was the epidemic that gay and lesbian rights activism in Saskatchewan had to rightfully turn its attention away from lobbying for human rights and onto lobbying for support for people with AIDS, an increase in safe sex education, and research for a treatment. Today, through this advocacy and with the support of allies, the homophobic violence directed at the gay community resulting from the HIV and AIDS crisis is strongly condemned.

AIDS Hysteria

From the beginning of the AIDS epidemic there was misinformation and hysteria surrounding the disease, which directly contributed to irrational homophobic violence against gay men. Many thought AIDS was more contagious than it was and were afraid to be in any contact with someone who was HIV/AIDS positive. Some said that AIDS was proof that being gay was dangerous to a person’s health, and some claimed that AIDS was God’s punishment for gay people.

From the beginning of the AIDS epidemic there was misinformation and hysteria surrounding the disease, which directly contributed to irrational homophobic violence against gay men. Many thought AIDS was more contagious than it was and were afraid to be in any contact with someone who was HIV/AIDS positive. Some said that AIDS was proof that being gay was dangerous to a person’s health, and some claimed that AIDS was God’s punishment for gay people.

Due to the combination of homophobia, stigma, misinformation, and shame, the families of people who passed from AIDS often tried to cover up or deny the cause of their death. Since same-sex couples were not legally recognized at the time, sometimes people’s partners were denied involvement in funeral arrangements and had no access to their partner’s possessions after passing. Many felt that the provincial and federal governments did not care and were not doing enough to prevent the spread of AIDS.

To get an idea of the type of widespread misinformation surrounding the epidemic, take a look at the words and actions of Saskatchewan politicians. During the 1991 provincial election, a Progressive Conservative candidate, Rev. John Bergen, called for “AIDS-free restaurants.” AIDS was proven to not be spread through food consumption.

The AIDS Crisis in Saskatchewan, 1980s

“In the mid-1980s, when AIDS came to the prairies, it would be teams of lesbians and gay men, particularly in Saskatoon and Regina, who pulled together to lead those volunteer organizations.”

-Valerie Korinek, Prairie Fairies: a history of queer communities and people in western Canada, 1930-1985.

During the 1980s activism in Saskatchewan was focused almost solely on the AIDS epidemic. Nearly all fundraisers became AIDS-related, and many community organizations turned their focus towards putting on social activities that raised AIDS awareness such as educational sessions, films, and art displays about the epidemic.

In 1983 Saskatchewan had its first recorded case of AIDS but it wasn’t until 1985 that the StarPhoenix started reporting on AIDS cases in the province. By 1987 there were 17 known cases in Saskatchewan.

In 1986 Toronto hosted the second Annual Canadian AIDS conference. At that conference the Canadian AIDS Society was founded, consisting of sixteen member groups spread across the country. AIDS Saskatoon and AIDS Regina were part of those original sixteen groups.

In 1987, the Royal University Hospital held a two-day symposium to provide advice to the government about AIDS programs. In 1990, various campus and community groups around Saskatoon sponsored an AIDS Awareness event that included a traveling exhibit of AIDS-related posters called Visual AIDS, film screenings, and speeches by AIDS activists. In Regina a People With AIDS (PWA) coalition was formed in 1988 to improve the quality of life of those in the Regina area living with the disease.

Indigenous AIDS Activism

By the early 1990s AIDS support groups had formed in nearly every urban centre in Canada. However, these support groups were mainly created by, and for, white men. Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) didn’t always connect with them. There were, however, plenty of Indigenous activists who worked to combat the epidemic. One of these individuals was activist Bob Mike, who travelled around Indigenous communities in Saskatchewan to share his experiences as an Indigenous man living with AIDS in the 1980s and early 1990s.

In 1999, The Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network was founded. Its mission was to provide Indigenous people living with AIDS a forum where they could discuss their experiences, and to help design AIDS-related, Indigenous-specific educational programs and services. In 2003 the group released their Aboriginal Strategy on HIV/AIDS in Canada, which proposed Canada-wide AIDS programs for Indigenous people. Groups of Indigenous activists across the United States and Canada organized AIDS programs that focused on decolonizing wellness promoting the de-stigmatization of both AIDS and sexual and gender diversity amongst Indigenous communities. For many, turning to traditional methods of healing allowed them to feel empowered and gain solidarity and support from within their own communities.

The Ongoing HIV Crisis

By the late 1980s, antiretroviral medications (ARV) were discovered to effectively treat HIV and AIDS by suppressing the HIV virus. Some claimed that the HIV/AIDS crisis was “over” by the late 90s. However, this was not completely true. There is still an HIV epidemic in Saskatchewan.

In 2000, AIDS Regina changed its name to AIDS Programs Southern Saskatchewan, and extended its outreach to more rural areas of the southern parts of the province.

|

|

In July 2020, after thirty-seven years of operation, AIDS Saskatoon changed its name to Prairie Harm Reduction. They remain committed to ending stigma surrounding HIV and Hepatitis C, reducing deaths, and providing services to those living with HIV and hepatitis. To learn more, visit their website.

|

|

Arts & Culture

Before Pride, the LGBTQ2S+ community found other ways to express themselves creatively and socially. Art has been and still is an important rallying point for the community, as well as a way for queer people to express their struggles, their pride, and take part in activism. Nowadays art is an important part of Pride festivals in Saskatchewan and around the world.

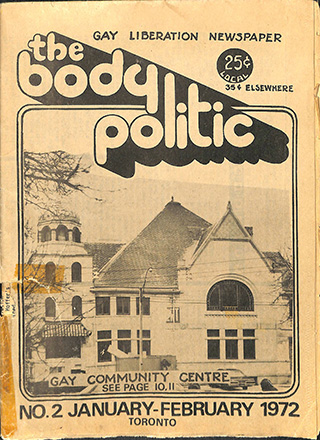

Newsletters and Periodicals

Social organizing and networking were integral to early LGBTQ2S+ communities. Before the Internet and social media, and in a time when mainstream news didn’t often discuss lesbian and gay issues, LGBTQ2S+ newsletters and periodicals were essential to helping members of these communities stay informed and connected with each other.

Social organizing and networking were integral to early LGBTQ2S+ communities. Before the Internet and social media, and in a time when mainstream news didn’t often discuss lesbian and gay issues, LGBTQ2S+ newsletters and periodicals were essential to helping members of these communities stay informed and connected with each other.

Initially, members of the Saskatchewan gay community stayed connected to the national LGBTQ2S+ scene by reading publications from larger urban centres. The first community organizations in Saskatchewan, Saskatoon Gay Action and the Gay Students Alliance, were started through Georgia Straight, an alternative news periodical based in Vancouver.

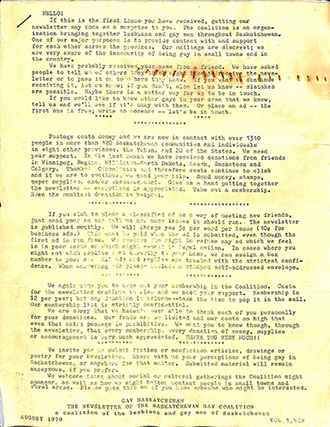

Gay Saskatchewan/Grassroots

Gay Saskatchewan/Grassroots

In 1978 Saskatchewan got its own LGBTQ2S+ newsletter. Activist Doug Wilson teamed up with Kay Bierwiler, a writer for a feminist periodical called Prairie Women: The Newsletter of Saskatoon Women’s Liberation, to start a newsletter called Gay Saskatchewan. Gay Saskatchewan, later renamed Grassroots, was the official newsletter of the Saskatchewan Gay Coalition, and was founded to help LGBTQ2S+ people in rural areas keep in touch with the wider Saskatchewan LGBTQ2S+ community. Unlike some the larger publications, which were mostly directed towards white gay men living in urban centres, Gay Saskatchewan/Grassroots tried to be as inclusive as possible to lesbians, rural, and Indigenous people.

Because people liked the diversity and unique perspectives of the newsletter, Gay Saskatchewan/Grassroots gained a large following that expanded beyond Saskatchewan’s borders. By the end of its publication, Gay Saskatchewan/Grassroots had a readership of 2,100 people from across Canada and the northern United States. Unfortunately, publication of Grassroots ended in 1982 due to volunteer burnout.

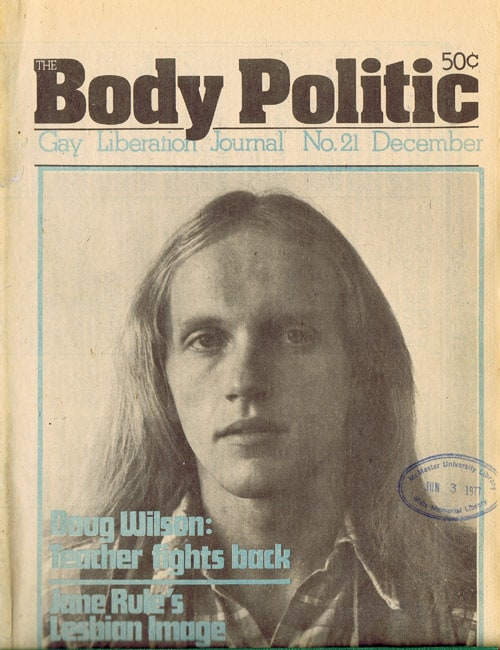

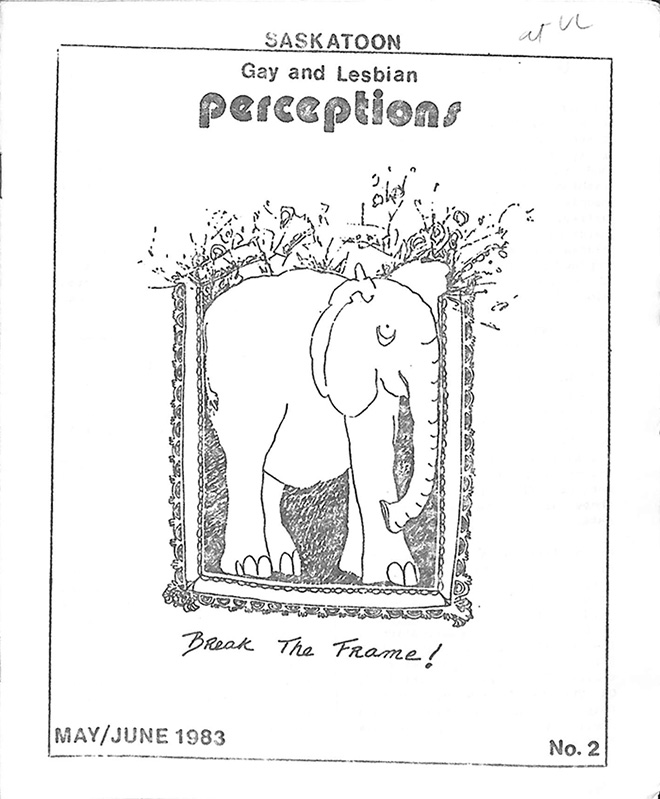

Perceptions

Perceptions

In 1983, activist Gens Hellquist founded another periodical in Saskatoon called Perceptions. By the 1990s, its reach had expanded across Saskatchewan and even into Alberta and Manitoba. Perceptions focused on providing information on resources to members of the queer community, keeping people informed on current events, and providing a forum for people to talk about their ideas and experiences. Perceptions ran until Hellquist passed in 2013. Its publication ran for an extraordinarily long time considering that many larger publications, like The Body Politic in Toronto, were not able to run for nearly that long.

Both Gay Saskatchewan/Grassroots and Perceptions were run by volunteers and funded by member subscriptions, donations, and fundraising events.

Nightlife

Safe socialization spaces have always been important to the LGBTQ2S+ community, whether this means a community centre to visit or somewhere to have fun on Friday and Saturday nights.

House Parties

House Parties

Before commercial clubs opened, house parties were an important part of LGBTQ2S+ social nightlife. House parties were private, safe spaces for people to meet each other, make friends within the community, and have fun. In some cases, they were also used as fundraising events. Activist Dan Nahlbach raised money to found and operate Saskatoon Gay Action by hosting house parties.

However, house parties were not perfect. One had to have a friend in the community in order to get invited, so it was hard for people new to the city or just figuring out their sexual orientation to get into them. A person’s continued invitation to house parties also largely depended on their ability to get along well with the host.

Clubs and Community Centres

Clubs and Community Centres

The formation of public community organizations helped solve some of the problems that house parties posed. In Saskatoon, the Gemini Club and later the Gay Community Centre of Saskatoon (GCCS), hosted dances and parties on the weekends.

In 1980 Saskatoon’s first commercial gay club, After Midnight, opened on Avenue B. Two years later it was renamed to Numbers and moved to multiple locations throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, finally settling on 3rd Avenue. In 1994, Numbers was renamed to Diva’s. Diva’s still operates today as Saskatoon’s premiere commercial gay club at the same 3rd Avenue location.

In Regina, nightlife and community organizations have remained intimately linked. In the 1970s Regina’s Odyssey Club on Smith Street was a privately-owned house that hosted its own parties and social events. In 1980 the Gay Community of Regina sold the Smith Street house and moved to a new location on Broad Street and in 1981 it became Regina’s first commercial gay club, Rumours. After a brief move to Scarth Street in 1985, Rumours moved back to Broad Street in 1999, where it still operates today as Q Lounge and Nightclub.

Drag

Experimenting with one’s gender expression has long been a cultural, social, and political tradition on the prairies but has only recently become associated with the queer community.

Experimenting with one’s gender expression has long been a cultural, social, and political tradition on the prairies but has only recently become associated with the queer community.

While drag queens were famously involved in the Stonewall riots in New York in 1969, drag remained a contentious issue in Saskatchewan for years. Some gay men disliked drag because they felt it equated gayness with exaggerated femininity, and some lesbians disliked it because they felt it was misogynistic. In fact, drag was banned from the GCCS in the 1970s.

However, there was still a drag presence in Saskatchewan from the 1970s onwards. Some people showed up to house parties in drag before commercial clubs were open, and AIDS-benefit drag shows were held in Saskatoon and Regina throughout the 1980s.

The Imperial Court System and Saskatchewan Drag Today

In 1965 in San Francisco, Jose Sarria founded the Imperial Court System of the United States, an organization uniting drag performers from across America. Individual cities, or sometimes whole states, have their own “court”: a non-profit organization lead by drag performers who are annually granted royalty-inspired titles through competition. Every year about 1-3 performers in each court win the title of “empress,” “emperor,” or any title of their choosing, and raise money for LGBTQ2S+ charities of their choice.

In 1965 in San Francisco, Jose Sarria founded the Imperial Court System of the United States, an organization uniting drag performers from across America. Individual cities, or sometimes whole states, have their own “court”: a non-profit organization lead by drag performers who are annually granted royalty-inspired titles through competition. Every year about 1-3 performers in each court win the title of “empress,” “emperor,” or any title of their choosing, and raise money for LGBTQ2S+ charities of their choice.

In 1971 Canada formed its own court system, starting in Vancouver, inspired by and united with the American one.

In 1989 Saskatoon formed the Imperial Court of the Prairie Lily. The first Imperial pageant was hosted at the Manhattan Ballroom, and performers Ghedo and Miss K were crowned Emperor I and Empress I respectively. Unfortunately, Saskatoon’s branch of the Imperial Court folded in 1993.

Instead of having a Saskatoon court, Diva’s Nightclub holds yearly competitions for the titles of Mr./Miss/Mx. Diva’s and Mr./Miss/Mx. Gay Saskatoon. The winners of the annual titles host drag shows throughout the year and do charity work. Drag Queen Crystal Clear was awarded the first Miss Diva’s title in 1998. In 1999 Richard Everhard became the first Mr. Diva’s.

In 1991 Regina formed its own branch of the Imperial Court System, the Imperial Court of the Golden Wheat Sheaf. This Imperial Court is still operating in Regina today. The court also awards Mr./Miss/Mx. Gay Regina titles alongside the royal titles.

Today, drag is a popular form of entertainment that draws viewers in from both inside the queer community and out. Drag shows are often included as part of yearly Pride festivals. Venues like Diva’s, Amigos Cantina, and Louis Loft in Saskatoon and Q Night Club in Regina hold regular shows. Drag shows are commonly held in bars and nightclubs where you must be the legal drinking age to attend, but occasionally are hosted in youth-friendly venues, such as in United Churches, for kids who are interested in drag performances, experimenting with their gender expression, or even performing themselves.

|

|

During the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, Saskatchewan drag performers came together and hosted multiple drag shows that were streamed live on the internet.

Art and Pride

Art has always been an important rallying point for the LGBTQ2S+ community. When recruiting members for the Saskatchewan Gay Coalition, Doug Wilson would host meetings that used queer films as a starting point. People interested in joining the coalition would watch a film, and then begin socializing by discussing it.

Showings of LGBTQ2S+ films, art displays, drag performances, live music, and theatrical productions have been integral ways for this community to gain visibility in the mainstream throughout the years. During the AIDS crisis art was a way to cope with losses, educate, and raise funds.

Art has remained an important part of Pride festivals. Musicians, drag performers, and other live entertainment as well as film screenings, fashion shows, and spoken word poetry have all historically been part of Pride. In 2020 the only in-person Pride event in Saskatoon was a drive-in screening of two documentaries: Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years, and The Archivettes. Festivities also included digitally streamed events like Wes Funk Memorial Pride Latte, a poetry event, and Pride in the Park, a combination of live-streamed performances by queer musicians and drag performers.

|

|

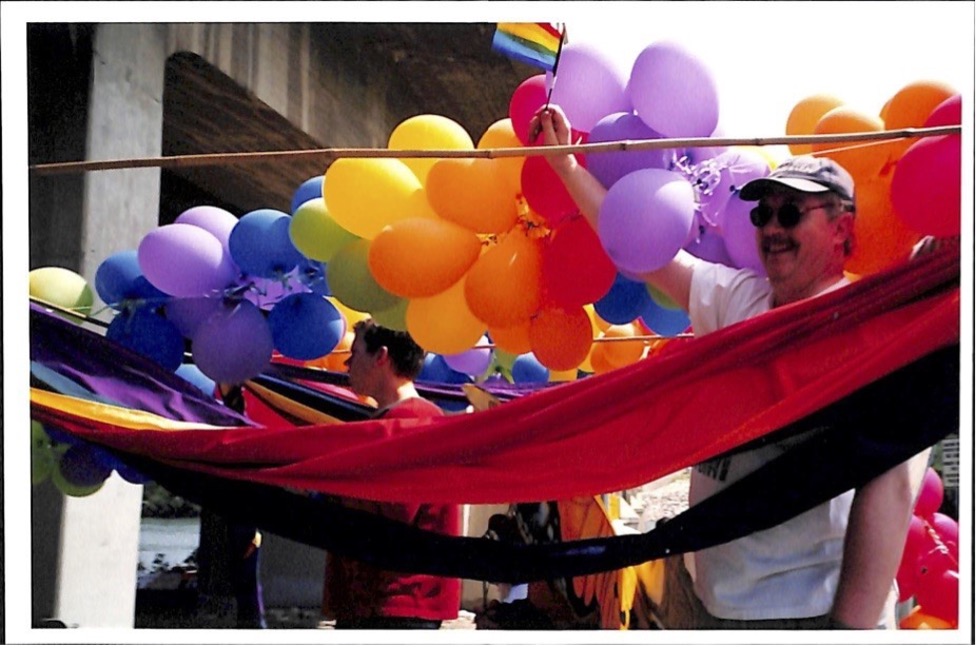

Pride

After the 20-year fight for gay and lesbian human rights finally accomplished major change, Pride celebrations kicked off as a significant summer festival in parts of Saskatchewan. Pride allows members of the queer community and their allies to come together, celebrate their identity, and be visible to the wider community. It is an opportunity for LGBTQ2S+ people to show that they are not ashamed to be themselves. Pride continues to be an important annual event for the queer community.

After the 20-year fight for gay and lesbian human rights finally accomplished major change, Pride celebrations kicked off as a significant summer festival in parts of Saskatchewan. Pride allows members of the queer community and their allies to come together, celebrate their identity, and be visible to the wider community. It is an opportunity for LGBTQ2S+ people to show that they are not ashamed to be themselves. Pride continues to be an important annual event for the queer community.

The First Pride

In August of 1973, activist Bruce Garman of Saskatoon Gay Action (SGA) requested permission from Saskatoon city council to hold a Pride Week so the gay and lesbian communities could publicly demonstrate pride in their sexuality and their wish to live without discrimination. City council rejected the request.

In August of 1973, activist Bruce Garman of Saskatoon Gay Action (SGA) requested permission from Saskatoon city council to hold a Pride Week so the gay and lesbian communities could publicly demonstrate pride in their sexuality and their wish to live without discrimination. City council rejected the request.

On September 2nd, 1973, despite city council’s rejection, SGA held an unofficial Pride picnic at Cranberry Flats. This was the first Pride celebration of any kind in Saskatchewan.

“Within the Canadian context, the hosting of two pride events in 1973, in Saskatoon and Winnipeg, was significant. Vancouver, Montreal, and Toronto would all inaugurate their pride traditions later, in 1978, 1979, and 1981 respectively, although there is evidence to suggest that early pride-like events were held in Vancouver in the early 1970s. Sexualities histories resist progressive narratives. These early pride events were not sustained, and due to a variety of circumstances, particularly the demands on volunteer organizers, provincial and urban politics, and the onset of the AIDS epidemic, many cities had long fallow periods before pride events were resurrected.”

-Valerie Korinek, Prairie Fairies: a history of queer communities and people in western Canada, 1930-1985.

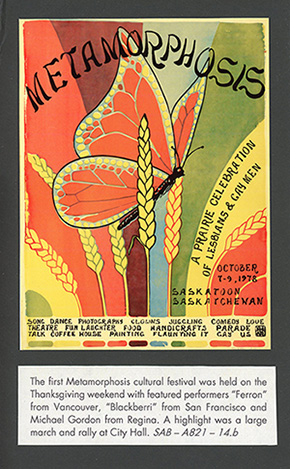

Metamorphosis

As tumultuous as the 1980s were for the gay and lesbian communities, one highlight in Saskatchewan was the Metamorphosis festival. Cultural, activism, and educational events were held over the Thanksgiving long weekend so that gay and lesbian people who were excluded from family gatherings had a place to celebrate and be part of a community.

As tumultuous as the 1980s were for the gay and lesbian communities, one highlight in Saskatchewan was the Metamorphosis festival. Cultural, activism, and educational events were held over the Thanksgiving long weekend so that gay and lesbian people who were excluded from family gatherings had a place to celebrate and be part of a community.

The first Metamorphosis was hosted by the Saskatchewan Gay Coalition (SGC) and held on Thanksgiving weekend of 1978.

The purpose of the festival was for gay and lesbian people to celebrate their identities and have positive visibility. The name Metamorphosis was chosen for symbolic reasons, as explained in a brochure for the original 1978 celebration:

“Metamorphosis according to one definition is a change in form by magic or natural development perhaps best exemplified by the transitions experienced in the development of the butterfly. Metamorphosis and the butterfly motif seem ideal as a metaphor for our continuing growth and coming out as individuals and as a gay community."

Not only was Metamorphosis notable because it was able to continue running in the 1980s, it was also significant because of the prominent lesbian presence at the festival. Over the course of its lifespan Metamorphosis attracted increasing numbers of lesbian guests, and lesbian activists progressively took more leadership roles in planning the event. Many lesbians felt that early gay activism was male-centric, so the female presence and leadership at Metamorphosis celebrations made them even more unique.

Metamorphosis ran annually until 1989, over which time it grew in popularity and started to attract guests from all over Canada.

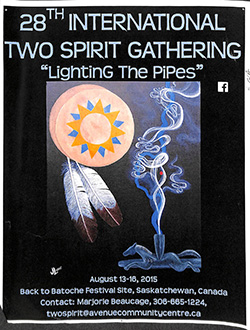

Early Two-Spirit Activism and Pride

Gender and sexually diverse Indigenous people have always lived in Saskatchewan. They lived their lives often with atypical gender roles and were respected and influential members of their communities with special spiritual and ceremonial responsibilities. There are as many different words for and versions of this identity as there are First Nations, Indigenous and Métis peoples.

It was European settlers that imposed the gender binary and heteronormative relationships on Indigenous peoples intentionally as a way to erase Indigenous cultures and assimilate Indigenous peoples into settler culture.

When gay and lesbian activism started to gain traction in the 1970s, anthropologists became interested in researching historical and cultural conceptions of gender and sexuality. Predominately white anthropologists began researching the history of a “third-gender” amongst Indigenous language groups. In the mid to late 1980s, Indigenous activists began to be critical of anthropological studies of their cultures and started to make efforts to reclaim historical Indigenous gender and sexually diverse identities for themselves.

In 1988, the first ever international gathering of American Indians and First Nations Gays and Lesbians was held in Minneapolis.

In 1988, the first ever international gathering of American Indians and First Nations Gays and Lesbians was held in Minneapolis.

“About fifty of us came together to celebrate the different ways we experience two-spiritedness. We held drug- and alcohol-free discussions, support groups, and dances. Participants represented many different First Nations in North America.”

-Two-Spirit Elder Ma Nee Chacaby

In 1990, at the third annual gathering of American Indians and First Nations Gays and Lesbians in Winnipeg, the term “Two-Spirit,” was proposed by Elder Myra Laramee. It was decided that this English phrase would be a blanket term applied to Indigenous queer identities. Labels such as gay, lesbian, transgender, or non-binary are settler creations; the term Two-Spirit was meant to be a complex term that did not correspond perfectly with any one settler identity label. It encompasses the variety of sexual and gender diversity amongst Indigenous cultures and is first and foremost an Indigenous identity label. Additionally, the term has allowed some to feel more in-touch with their Indigenous identities and become more comfortable partaking in their own communities.

“So for me Two-Spirit is an English word. And if you look at First Nations communities there are different language groups and within different language groups there are many communities...So, when I think about the word Two-Spirit it is an English term that describes First Nations and queer people all across the world... I understand why it exists and I describe myself that way and I use the Two-Spirit term but I much, much prefer to use the term in my own language meant for people like me. So in Plains Cree that would be napêhkân, and that means man-like. I definitely don’t feel like a man, I identify as a woman, but back then, in traditional times when our languages were commonly used, it was a descriptor and that was the best description that they had back then. So I love and own that term as well, napêhkân. So that is the term that I would prefer to use, however, Two-Spirit is absolutely fine and it’s also a good term to use to help people understand.”

-Melody Wood, Saskatchewan Indigenous Cultural Centre.

|

|

Official Pride Celebrations

Saskatoon and Regina in the 1980s and 1990s

In June of 1989 Regina City Council declared an official Pride weekend, becoming Saskatchewan’s first official pride celebration supported by a city government. The success was short-lived, however, as the decision received so much backlash from conservative communities in Regina that it would be years before another official Pride ceremony would be declared. In the meantime, members of the Regina queer community held unofficial pride celebrations and protest marches each June to maintain their visibility.

In 1993, for the first time in twenty years, Saskatoon held another, unofficial, Pride celebration. Bill C-38, granting gay and lesbian people in Saskatchewan their basic human rights, was passed only a few days afterwards. The festivities included a film screening at the Broadway Theatre and an awards ceremony for activists who had led and served the gay and lesbian communities.

In May of 1994, after sexual orientation had been added to the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, Saskatoon City Council was again asked to proclaim an official Pride Day. Council rejected the request, and the Saskatoon Pride Committee filed a complaint with the Saskatoon Human Rights Commission.

Finally, on June 6, 1995, the City of Saskatoon proclaimed its first official Pride Day. In 1999 Regina City Council proclaimed its second official Pride celebration after ten years since the first one. Since then, Regina and Saskatoon have each held Pride celebrations annually.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pride in Saskatchewan's Smaller Communities

Mainstream Pride activities have also seen increasing Two-Spirit participation over time. Events such as Two-Spirit pow wows and drum circles are now part of Pride festivities across the province. In 2016 the Beardy’s and Okemasis Cree Nation held their first Two-Spirit Pride celebration, marking the first time a First Nation held a Two-Spirit Pride celebration in Saskatchewan.

“Typically Two-Spirit people either walk a traditional lifestyle, or they balance the western and traditional lifestyle, so there were a bunch of Two-Spirit people who didn’t really want the main stage and the party, they wanted ceremony and acknowledgment of what it means to be Two-Spirit in the First Nations traditional way of life... Now there is the Two-Spirit powwow, usually before pride, it’s leading up to pride...I know that there is a pipe ceremony as well, so it is more of a quiet celebration again. It’s not a hugely advertised like most pride events are.”

-Melody Wood, Saskatchewan Indigenous Cultural Centre

|

|

|

Continuing to Celebrate Pride in Saskatchewan

It took twenty long years of protest, organization, and activism for Saskatchewan to see an officially recognized Pride celebration. Despite how difficult it was for Pride to be acknowledged, in the short amount of time since its inauguration it has become recognized as a major and important annual celebration. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 Pride organizations across the province organized digital pride festivals with live-streamed events.

|

|

|

Homophobia and gender discrimination still exists throughout Saskatchewan, but Pride celebrations allow members of the queer community and their allies to publicly celebrate their identity in solidarity with one another and make themselves and their human rights issues visible. As an important annual event, Pride is an ever-growing celebration that welcomes diverse groups of people and will continue to be celebrated in Saskatchewan.

Acknowledgements

The Diefenbaker Canada Centre would like to thank everyone who helped us create this exhibit. It was important to the DCC to co-create this exhibit with members of Saskatchewan’s queer community in order to empower individuals by providing a platform in which they can share their experiences. This exhibit is one of the DCC’s first steps in showing our solidarity with the queer community, so it was important for us to engage with community members. A museum exhibit cannot be created alone, and we have had incredible support from members of the Saskatoon and University of Saskatchewan Community. From the heart we thank everyone who contributed to making this exhibit possible. Among many we would like to extend special thank-yous to:

Dr. Valerie J. Korinek

Dr. Korinek is a professor in the University of Saskatchewan’s department of History. Dr. Korinek is the author of several papers on queer history in Western Canada. In 2018 she published Prairie Fairies: A History of Queer Communities and Peoples in Western Canada, 1930-1985. Dr. Korinek’s work informs a large portion of this exhibit. She also consulted with us on the creation of this exhibit and gave us feedback on the text before it was published. Thank you very much Dr. Korinek, without your work and your help this exhibit would not have been possible.

Rene Clarke

Rene is the 2020-2021 USSU Pride Centre Coordinator. They are a previous Pride Centre volunteer and a psychology major, passionate about mental health, social justice, and harm reduction, whose dream is to become a therapist and make sure the vulnerable get the help they need. Rene collaborated with the DCC on this project, providing us with feedback on our exhibit draft, designing social media posts, and helping us get in touch with community groups. Thank you very much for all of your help Rene, you helped us get this exhibit off the ground.

An additional thank you goes out to all the Pride Centre volunteers who are working hard to create a safe space for LGBTQ2S+ students.

Neil Richards

Neil Richards was an activist and University of Saskatchewan librarian. He made it his life’s work to collect and archive memorabilia related to LGBTQ2S+ history in Saskatchewan. Many of the images included in this exhibit are from the University of Saskatchewan’s Neil Richards Collection of Sexual and Gender Diversity, which he personally collected. Additionally, he wrote Celebrating a History of Diversity: Lesbian and Gay Life in Saskatchewan, 1971-2005, which was a major resource in informing this exhibit. Neil Richards passed away in 2018, but his legacy lives on in his work. He was posthumously awarded the Saskatchewan Order of Merit for his contributions to the province. We thank Neil Richards and sincerely hope that this exhibit honours his legacy. Without his pioneering work in documenting Saskatchewan’s LGBTQ2S+ history this exhibit would not have been possible.

Melody Wood

Melody Wood is the Indigenous Knowledge Systems Researcher at the Saskatchewan Indigenous Cultural Centre (SICC) and a Plains Cree, Two-Spirit woman. Melody consulted with us on how to communicate with Elders, as well as reviewed the Two-Spirit related content of the exhibit. Thank you very much Melody, your advice was essential in helping this exhibit be as culturally inclusive and respectful as possible. Melody also agreed to sit down and interview with us. Thank you, Melody, for sharing your knowledge and experience with the DCC in order to enrich this exhibit.

Jack Saddleback

Jack Saddleback is the Cultural and Projects Coordinator at OUTSaskatoon. He is a Two-Spirit transgender gay man from the Samson Cree Nation in Maskwacis, Alberta. Jack consulted with us on this exhibit, gave us advice on how to reach out to community members, and edited the exhibit draft for accuracy and respectfulness. Thank you very much for contributing your knowledge to this exhibit.

The University of Saskatchewan Archives and Special Collections

Archives and Special Collections provided the majority of the images included in this exhibit. The archival staff sent us images related to our project and assisted us in getting access to their collections. Even during the COVID-19 pandemic they were able to provide us safe access to the Neil Richards Collection in the archives so that we could build this exhibit. Thank you to all the Archives and Special Collections staff for helping us make this exhibit visually richer.

All of Our Interviewees

An important part of creating this exhibit was speaking to members of Saskatchewan’s queer community who were here to personally witness historic events. A huge thank-you goes out to everyone who agreed to be interviewed. Thank you for sharing your knowledge with us and allowing us to get a better sense of what the historic events we read about were really like. Your contributions both to this exhibit and to Saskatchewan’s queer community are greatly appreciated. The interviewees who wished to be acknowledged by name are:

- Melody Wood

A Special Thank you goes out to everyone else who contributed images to this exhibit. Your generosity has allowed us to showcase the vibrancy of Saskatchewan’s current LGBTQ2S+ community. Thank you to:

- AIDS Programs Southern Saskatchewan

- The ArQuives

- The Gay and Lesbian Community of Regina

- Jory McKay

- Moose Jaw Public Library and Archives

- Natalie Struck

- OUTSaskatoon

- Prairie Harm Reduction

- Queen City Pride

- UR Pride

- The USSU Pride Centre

- Sarah Barnsley

- Saskatoon Pride

- Saskatchewan Government Insurance

- Southwest Saskatchewan Pride

About Us

The Diefenbaker Canada CentreClick here to learn about the Diefenbaker Canada Centre's mandate, collection, exhibits, and programming.

Megan Gorsalitz

Megan Gorsalitz is the curator for this exhibit. As the Exhibit and Collections Assistant, she was one of the DCC’s 2020 summer student employees funded by Young Canada Works and Canada Summer Jobs; at the time of her employment she had just finished an undergraduate degree in Linguistics, and was working on a second undergraduate degree in English Literature.

Around the time of the beginning of her employment at the DCC, there were several instances of homophobic graffiti appearing around Saskatoon. Upset and wanting to do something about it, Megan decided to create this exhibit in hopes that it would educate people about the difficult history of queer community and the importance of showing pride, as well as allow Saskatchewan’s queer community to connect with our own, often-erased history. She hopes that this exhibit can be helpful, even if only to one person.

Helanna Gessner

Helanna Gessner is the Curatorial, Collections, and Exhibits Manager of the DCC. She provided Megan with supervision and guidance throughout the curation of the exhibit.

Glossary*

Cisgender: Identifying with the same gender that one was assigned at birth. A gender identity that society considers to match the biological sex assigned at birth. The prefix cis means “on this side of” or “not across from.” A term used to call attention to the privilege of people who are not trans.

Coming out: Or, ‘coming out of the closet,’ is the process of becoming aware of one’s queer sexual orientation, one’s 2-Spirit or trans* identity, accepting it, and telling others about it. This is an ongoing process that may not include everybody in all aspects of one’s life. ‘Coming out’ usually occurs in stages and is a non-linear process. An individual may be ‘out’ in only some situations or to certain family members or associates and not others. Some may never ‘come out’ to anyone besides themselves.

Drag: Refers to people who dress in a showy or flamboyant way that exaggerates gendered stereotypes, often for entertainment purposes. ‘Drag’ is a term that is often associated with gay/ lesbian communities and is often replaced with ‘Drag King’ and ‘Drag Queen.’ Some people who perform professionally outside gay/lesbian communities prefer the term ‘male/female impersonator.’

Gay: A person who is mostly attracted to those of the same gender; often used to refer to men only.

Gender: The social construction of concepts such as masculinity and femininity in a specific culture and time. It involves gender assignment (the gender designation of someone at birth), gender roles (the expectations imposed on someone based on their gender), gender attribution (how others perceive someone’s gender), and gender identity (how someone defines their own gender). Fundamentally different from the sex one is assigned at birth.

Gender Binary: The view that there are only two totally distinct, opposite and static genders (masculine and feminine) to identify with and express. While many societies view gender through this lens and consider this binary system to be universal, a number of societies recognize more than two genders. Across all societies there are also many folks who experience gender fluidly, identifying with different genders at different times.

Gender Expression: How one outwardly manifests gender; for example, through name and pronoun choice, style of dress, voice modulation, etc. How one expresses gender might not necessarily reflect one’s actual gender identity.

Gender Identity: One’s internal and psychological sense of oneself as male, female, both, in between, or neither. People who question their gender identity may feel unsure of their gender or believe they are not of the same gender as their physical body. Gender non-conforming, gender variant, or genderqueer are some terms sometimes used to describe people who don’t feel they fit into the categories of male or female. ‘Bi-gender’ and ‘pan-gender’ are some terms that refer to people who identify with more than one gender. Often bi-gender and pangender people will spend some time presenting in one gender and sometime in the other. Some people choose to present androgynously in a conscious attempt to challenge and expand traditional gender roles even though they might not question their gender identity.

Gender Non-conforming: This term refers to people who do not conform to society’s expectations for their gender roles or gender expression. Some people prefer the term ‘gendervariant’ among other terms.

Genderqueer: A term under the trans* umbrella which refers to people who identify outside of the male-female binary. Genderqueer people may experience erasure if they are perceived as cisgender. Genderqueer people who are perceived as genderqueer are often subjected to gender policing. Related but not interchangeable terms include ‘gender outlaw’, ‘gender variant’, ‘gender non-conformist’, ‘third gender’, ‘bigender’, and ‘pangender’.

Heterosexual: A person who primarily feels physically and emotionally attracted to people of the ‘opposite’ gender; also sometimes referred to as ‘straight’.

Homophobia: Fear or hatred of, aversion to, and discrimination against homosexuals or homosexual behaviour. There are many levels and forms of homophobia, including cultural/institutional homophobia, interpersonal homophobia, and internalized homophobia. Many forms of homophobia are related to how restrictive binary gender roles are (see ‘oppositional sexism’). An example of this might be a lesbian who is harassed with homophobic language for being perceived to be masculine. Many of the problems faced by lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, including health and income disparities, stem from homophobia and heterosexism. See also biphobia, lesbophobia, transphobia and LGBT-phobia.

Homosexual: A person who is mostly attracted to people of their own gender. Because this term has been widely used negatively and/or in a cold and clinical way, most homosexuals prefer the terms ‘lesbian’, ‘gay’ or ‘queer’.

LGBTQ: Acronym used to refer to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender people, interchangeable with GLBT, LGTB, etc. Additional letters are sometimes added to this acronym, such as LGBTIQQ2S to refer to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, Queer, Questioning and Two-Spirit folk. Making fun of the length of this acronym can have a trivializing or erasing effect on the group that longer acronyms seek to actively include.

Lesbian: A woman who is primarily romantically and sexually attracted to women. The term originates from the name of the Greek island of Lesbos which was home to Sappho, a poet, teacher, and a woman who loved other women. Although not as common, sometimes the term ‘gay woman’ is used instead.

Non-Binary: Used to describe people who experience their gender identity and/or gender expression outside of the male-female gender binary. Many other words for identities outside the traditional binary may be used, such as genderfluid, genderqueer, polygender, bigender, demigender, or agender. These identities, while similar, are not necessarily interchangeable or synonymous.

Queer: A term becoming more widely used among LGBT communities because of its inclusiveness. ‘Queer’ can be used to refer to the range of non-heterosexual and non-cisgender people and provides a convenient shorthand for ‘LGBT’. It is important to note that this is a reclaimed term that was once and is still used as a hate term and thus some people feel uncomfortable with it. Not all trans* people see trans* identities as being part of the term ‘queer’.

Rainbow Flag/Colours: A symbol of queer presence, welcome, and pride which represents the diversity of queer communities.

Sex: Refers to the biological characteristics chosen to assign humans as male, female or intersex. It is determined by characteristics such as sexual and reproductive anatomy and genetic make-up.

Sexual Orientation: Refers to a person’s deep-seated feelings of sexual and romantic attraction. These attractions may be mostly towards people of the same gender (lesbian, gay), another gender (heterosexual), men and women (bisexual), or people of all genders (pansexual). Many people become aware of these feelings during adolescence or even earlier, while some do not realize or acknowledge their attractions (especially same-sex attractions) until much later in life. Many people experience sexual orientation fluidly, and feel attraction or degrees of attraction to different genders at different points in their lives. Sexual orientation is defined by feelings of attraction rather than behaviour.

Transgender (Trans, Trans*): Transgender, frequently abbreviated to ‘trans’ or ‘trans*’ (the asterisk is intended to actively include non-binary and/or non-static gender identities such as genderqueer and genderfluid) is an umbrella term that describes a wide range of people whose gender identity and/or expression differs from conventional expectations based on their assigned biological birth sex. Some of the many people who may or may not identify as transgender, trans, or trans* include people on the male-to-female or female-to-male spectrums, people who identify and/or express their gender outside of the male/female binary, people whose gender identity and/or expression is fluid, people who explore gender for pleasure or performance, and many more. Identifying as transgender, trans, or trans* is something that can only be decided by an individual for themselves and does not depend on criteria such as surgery or hormone treatment status.

Transition: Refers to the process during which trans* people may change their gender expression and/or bodies to reflect their gender identity or sexual identity. Transition may involve a change in physical appearance (hairstyle, clothing), behaviour (mannerisms, voice, gender roles), and/or identification (name, pronoun, legal details). It may be accompanied by changes to the body such as the use of hormones to change secondary sex characteristics (e.g. breasts, facial hair).

Trans Man: This term describes someone who identifies as trans* and whose gender identity is male.

Trans Woman: This term may describe someone who identifies as trans* and whose gender identity is female.

Transphobia: The fear and dislike of, and discrimination against, trans* people. Transphobia can take the form of disparaging jokes, rejection, exclusion, denial of services, employment discrimination, name-calling and violence.

Two-Spirit: A term used by some North American Aboriginal societies to describe people with diverse gender identities, gender expressions, gender roles, and sexual orientations. Dual-gendered, or ‘two-spirited,’ people have been and are viewed differently in different First Nations communities. Sometimes they have been seen without stigma and were considered seers, child-carers, warriors, mediators, or emissaries from the creator and treated with deference and respect, or even considered sacred, but other times this has not been the case. As one of the devastating effects of colonization and profound changes in North American Aboriginal societies, many Two-Spirit folk have lost these community roles and this has had far-reaching impacts on their well-being.

Acronyms

GCCS: The Gay Community Centre of Saskatoon, a community organization in the 1970s and 1980s formed out of SGA and ZFS.GLCR: The Gay and Lesbian Community of Regina, originally called the Atropos Friendship Society. This community organization was founded in the early 1970s and still operates today, making it the longest-running LGBTQ2S+ community organization in Saskatchewan.

GLSS: Gay and Lesbian Support Services, a community organization of Saskatoon founded by Gens Hellquist in the 1980s. GLSS focused on supporting the well-being of the queer community.

GLHS: Gay and Lesbian Health Services, another community organization founded by Gens Hellquist in the 1990s. GLHS eventually became OUTSaskatoon.

SGA: Saskatoon Gay Action, the first gay community organization in Saskatoon in 1971, founded through an advertisement in Vancouver’s Georgia Straight and focused on activism.

SGC: The Saskatchewan Gay Coalition, an organization founded by Doug Wilson in the 1970s focused on outreach to rural communities.

ZFS: The Zodiac Friendship Society, a community organization founded in Saskatoon in the 1970s that focused on socialization.

*The definitions in this glossary are taken from “Queer Terminology – from A to Q” by the QMUNITY, British Columbia’s Queer Resource Centre and the Trevor Project.

Bibliography

Books

Chacaby, Ma-Nee and Plummer, Louisa. A Two-Spirit Journey: The Autobiography of a Lesbian Ojibwa-Cree Elder. Association of Canadian University Presses, 2016.

Korinek, Valerie. Prairie Fairies: A History of Queer Communities and People in Western Canada, 1930-1985. Toronto UP, 2018.

McNinch, James and Mary Cronin, eds. I Could Not Speak My Heart: Education and Social Justice for Gay and Lesbian Youth. University of Regina Press, 2004.

Morgensen, Scott Lauria. Spaces Between Us Queer Settler Colonialism and Indigenous Decolonization. Minnesota UP, 2011.

Richards, Neil. Celebrating a History of Diversity: Lesbian and Gay Life in Saskatchewan, 1971-2005. A Selected Annotated Chronology. The Avenue Community Centre for Gender and Sexual Diversity Inc., 2005.

Warner, Tom. Never Going Back: A History of Queer Activism in Canada. Toronto UP, 2002.

Wilchins, Riki. “Transgender Rights.” Gender and Women’s Studies in Canada, edited by Margaret Hobbs and Carla Rice, pp. 183-187. Toronto UP, 2013.

Journal Articles

Butler, Paul. “Embracing AIDS: History, Identity, and Post-AIDS Discourse.” JAC, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 93-111. JStor, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20866614.

Driskill, Qwo-Li. “Doubleweaving Two-Spirit Critiques: Building Alliances Between Native and Queer Studies.” GLQ vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 69-92. Duke UP, doi: 10.1215/10642684-2009-013.

Forstein, Marshall. “AIDS: A History.” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 40-63. EBSCOhost, doi: 10.1080/19359705.2013.740212.

Korinek, Valerie J.. “Doug Wilson and the Politicization of a Province 1975-83.” The Canadian Historical Review, vol. 84, no. 4, pp. 517-550. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/docview/224274773?accountid=14739.

Korinek, Valerie J. “Activism = Public Education: The History of Public Discourses of Homosexuality in Saskatchewan, 1971-93” in J. McNinch and M. Cronin, eds. I Could Not Speak My Heart: Education and Social Justice for Gay and Lesbian Youth (University of Regina Press, 2004).

Korinek, Valerie. “VOICES of Gay, Lesbian, and Feminist Activists in the Prairies.” American Periodicals: A Journal of History & Criticism, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 123-138. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/702111.