Lost Opportunities

Prior to 1962, there were no comprehensive Indigenous treaty rights or land claims policies in Canada, therefore, the Federal Government addressed specific claims on a case-by-case basis. Diefenbaker proposed the creation of an Indian Specific Claims Commission to be supported by legislation – Bill C-130. The Bill was approved by Cabinet, but was never introduced in Parliament. It, and other policy advancements, were scuttled when Diefenbaker lost the 1963 general election to Lester B. Pearson.

A Vision for the North

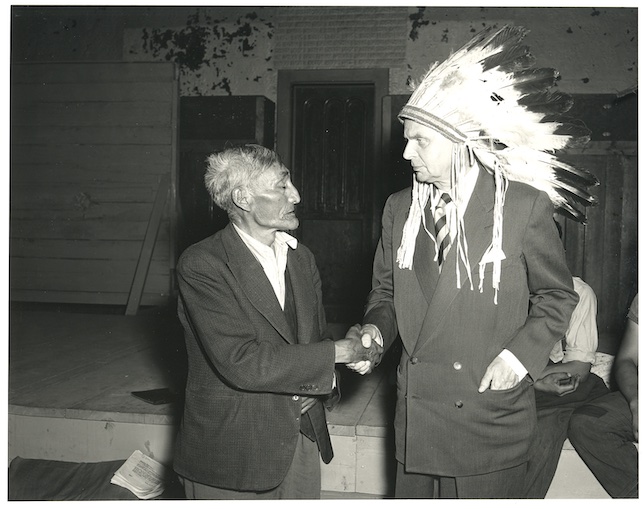

During the 1958 election campaign, Diefenbaker announced his “Northern Vision” — a bold strategy designed to stimulate natural resource-based research and fiscal growth in inaccessible and underdeveloped regions of Canada. The goal was also intended to assert Canadian sovereignty against American economic influences. The “Vision” inspired Canadian voters, fueling the wave of support that propelled Diefenbaker’s government into power.

“…when the vast movement was taking place into the Western plains, [pioneers] had imagination. There is a new imagination now. The Arctic. A new vision. A new hope! A new soul for Canada.”

– Diefenbaker, 1958

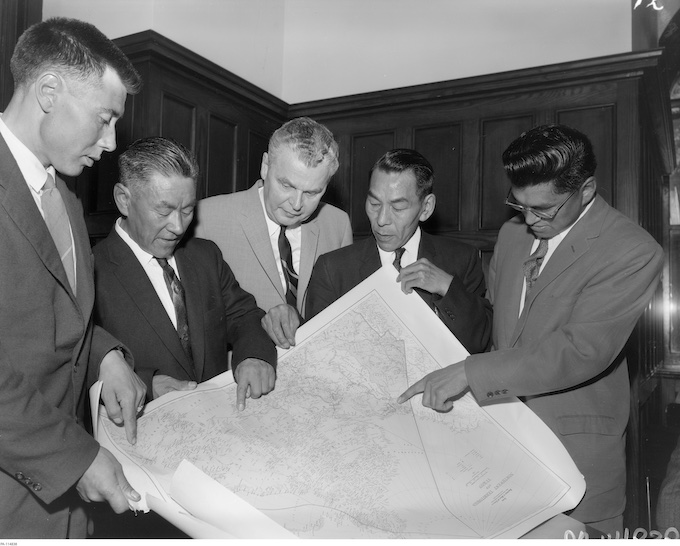

Roads to Resources

A key component of the “Vision” was a massive investment in transportation infrastructure development. Intended to create thousands of new jobs, the “Roads to Resources” program appealed to a belief that the North was the last great Canadian frontier. Undertaken through cost-sharing arrangements between the Federal Government and the Territories, the project focused on creating a system of grid-roads in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories. By the spring of 1963, over 6,000 km of highway had been completed.

Promise and Reality

The potential of the “Northern Vision” was plagued by financial and jurisdictional difficulties. Scheduled for completion in five to seven years, costs exploded from $30 million to $100 million. Although the project fell short of its goals, it continued to inspire Canadians. In 2017, the Federal government and Yukon Territory committed $360 million to the “Yukon Resource Gateway Project," which will allow for infrastructure improvements and the construction of more than 650 km of road.

|

|

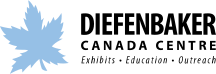

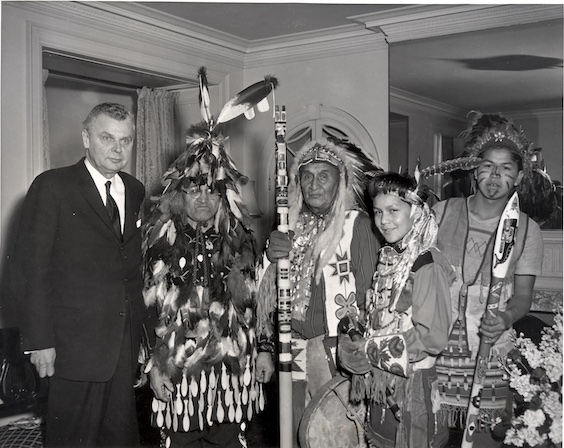

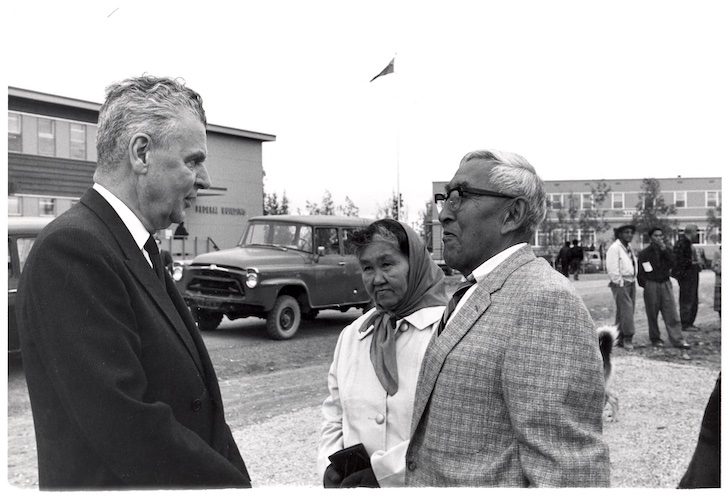

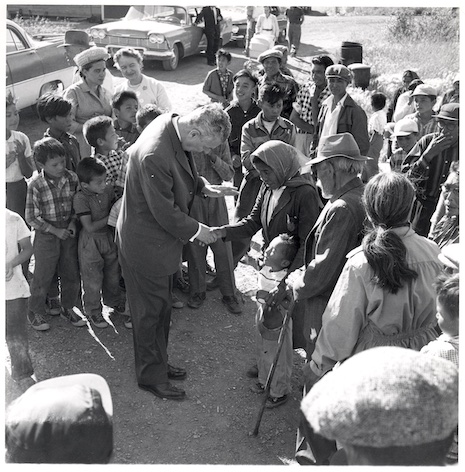

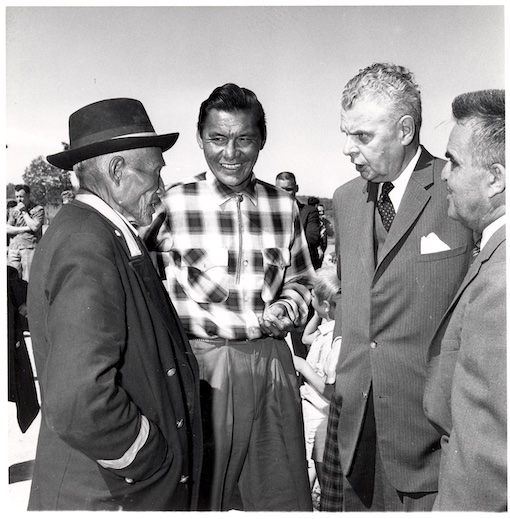

A Significant Oversight

One crucial perspective was overlooked during the planning and implementation of the “Northern Vision” program: that of Indigenous peoples. Aspects of the "Vision,” such as the construction of northern highways, had unforeseen consequences for the welfare of Aboriginal and Inuit communities. This lack of consultation stands in stark contrast to Diefenbaker’s otherwise steadfast support of Indigenous rights.