Le Premier and the Chief

With only a basic understanding of French Canada’s history and limited French language skills, Diefenbaker faced an uphill battle to gain support in Québec. Premier Maurice Duplessis indicated that his party – the Union Nationale – would be willing to endorse the Tories in the 1958 election. In return, he required Diefenbaker’s promise to uphold the provincial autonomy guaranteed to Québec during Confederation. Diefenbaker refused.

“He had the same difficulty that any westerner has in dealing with French Canada. He didn’t have enough daily association with it to fully understand it, to understand [its] nuances and pitfalls….”

- Tommy Douglas, 1976

The Duplessis Deception

Following Diefenbaker’s refusal, Duplessis attempted to reach him through Pierre Sévigny, a member of Diefenbaker’s government who was sympathetic to the Québec Premier’s cause. When Sévigny could not extract a guarantee, the two men resorted to trickery. Taking advantage of Diefenbaker’s lack of French language skills, prior to a dinner in Montréal, they replaced Diefenbaker’s prepared remarks with a speech from Duplessis. Diefenbaker was initially infuriated, but was appeased once he discovered his support in Québec was increasing.

Helping Make History

Duplessis maintained that ensuring provincial independence was necessary to maintaining Québécois culture and society. He was frustrated by Diefenbaker’s refusal to honour what the Premier regarded as a binding agreement between Québec and the Federal Government. Duplessis countered by minimizing the Union Nationale’s support, but soon his party realized that Diefenbaker was gaining popularity in Québec. Duplessis then threw his party’s backing behind the Progressive Conservatives, contributing to the Tories’ 1958 win.

“On Monday, March 31st, 1958, Mr. Pearson’s Liberal party lost 58 seats, more than 40 of them in Québec, which, until then, had been an unbreachable Liberal stronghold for three solid generations.”

– CBC Newsmagazine, 290th Edition, 1958

|

|

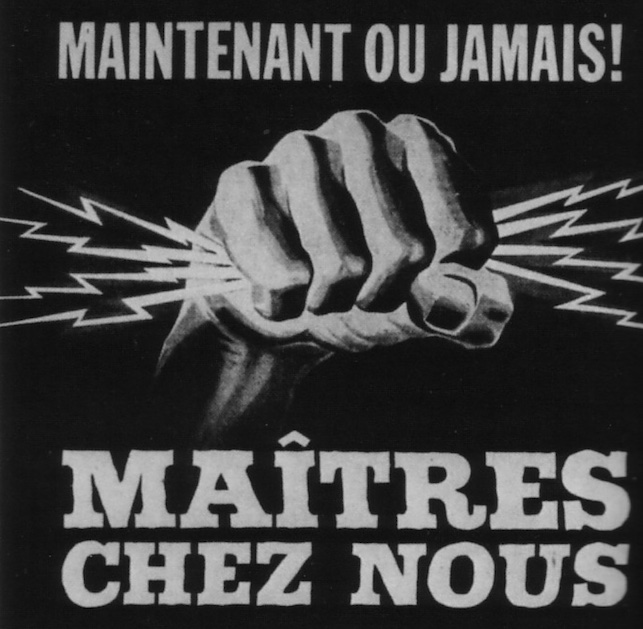

Genesis of a Revolution

After Premier Duplessis died, Jean Lesage’s « Parti liberal du Québec » (Québec Liberal Party) swept into power in the 1960 provincial election, triggering « la Révolution tranquille » (the “Quiet Revolution”). This political change reflected an awakening in Québec: a revival of separatist sentiments, a rejection of the Catholic Church’s socio-political influence, and a surge of cultural, public welfare and economic amendments. Diefenbaker was troubled by these radical shifts.

“Mr. Diefenbaker had [a] very typical westerner’s conception of Quebec. He believed [he only had to] say a few words in French, and make a few token gestures and all would be well.”

– Paul Martineau, 1959

|

|

Reaching Out

Attempting to respond to concerns in Québec, the Tories introduced a number of reforms intended to benefit French Canadians. Upon Diefenbaker’s recommendation, Queen Elizabeth II appointed Georges Vanier as the first Québécois Governor General in 1959. That same year, simultaneous interpretation was introduced in the House of Commons. Diefenbaker continued to face a highly critical Québec however, and many Francophones viewed his efforts as mere tokenism.

A Final Stand

Diefenbaker’s final stand on the issue of Québécois rights occurred at the Progressive Conservative leadership convention in 1967. Diefenbaker’s platform was based on his enduring vision of “One Canada” and firm opposition to a proposed party resolution to officially recognize “deux nations au Canada” or “two nations in Canada.” Diefenbaker withdrew as a candidate after finishing fifth on the third ballot; the controversial resolution was ultimately rejected by the delegates.