Firm Foundations

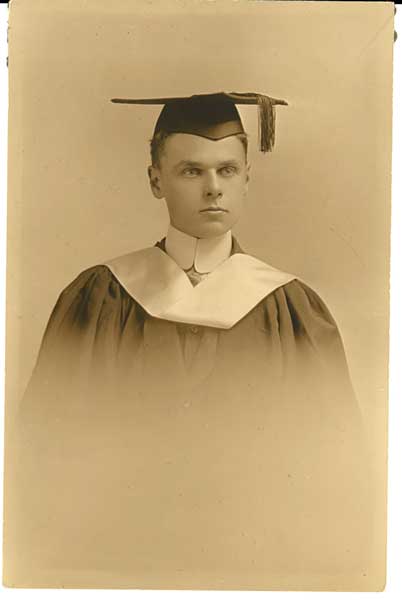

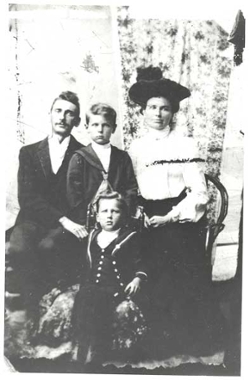

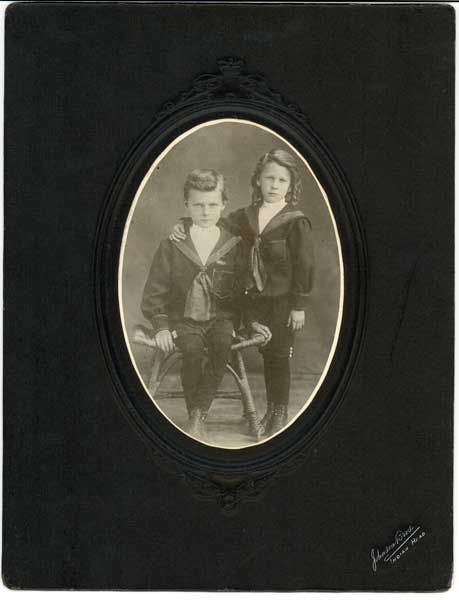

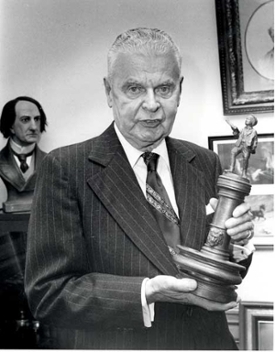

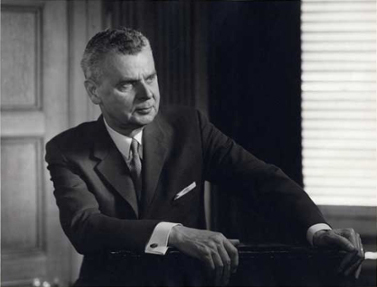

John George Diefenbaker was born on 18 September 1895 in Neustadt, Ontario. In 1903 he, his younger brother Elmer and their parents William and Mary, moved to a homestead near Borden, Saskatchewan. In 1910, the family relocated to Saskatoon where Diefenbaker graduated from Nutana Collegiate.

Diefenbaker’s admiration for his parents was undeniable. He attributed his quest for knowledge to his father and his unrelenting determination to his mother.

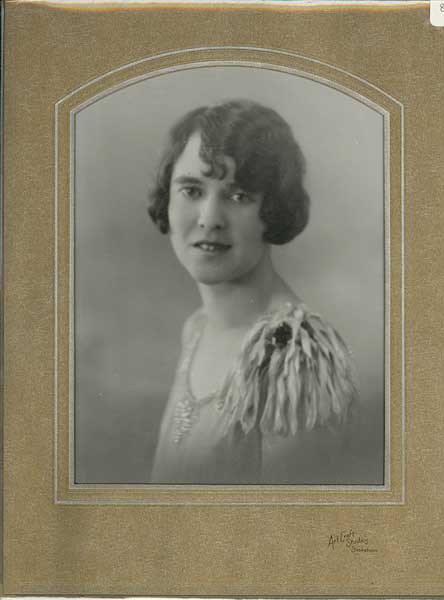

In June of 1929, Diefenbaker married Edna Mae Brower, a teacher. During his early political career, Edna was her husband's strongest and most dedicated supporter. She died of leukemia in 1951 and is interred in the Diefenbaker family plot at the Woodlawn Cemetery in Saskatoon.

In 1953, Olive Freeman Palmer became Diefenbaker's second wife. Although the couple never had any children, they raised Carolyn, Olive's daughter from her previous marriage.

|

|

|

A Memorable Moment

In 1910, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier came to the University of Saskatchewan campus to lay the cornerstone for the College Building. While touring downtown Saskatoon, Laurier purchased a newspaper from a paperboy and the two began talking. After a while the lad ended the conversation saying, “Sorry Prime Minister, I can’t waste any more time. I’ve got to sell my papers!"

The experience made such an impression on Laurier that he mentioned the paperboy during his speech on campus. According to Diefenbaker, he was that boy.

John G. Diefenbaker and the University of Saskatchewan

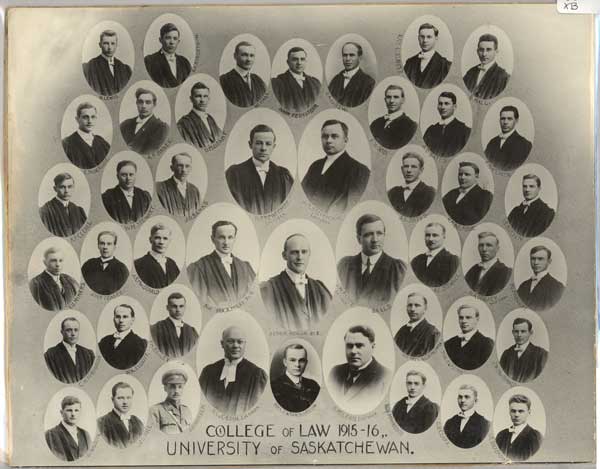

Long before John Diefenbaker became Prime Minister, he was a student at the University of Saskatchewan, where he earned his Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Economics. He also received a Master of Arts degree in absentia, while serving in England with the 196th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces (a battalion comprised of students and professors from universities in western Canada). In 1919, he finished a Bachelor of Law Degree and became the first person to complete three degrees from the University of Saskatchewan.

Long before John Diefenbaker became Prime Minister, he was a student at the University of Saskatchewan, where he earned his Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Economics. He also received a Master of Arts degree in absentia, while serving in England with the 196th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces (a battalion comprised of students and professors from universities in western Canada). In 1919, he finished a Bachelor of Law Degree and became the first person to complete three degrees from the University of Saskatchewan.

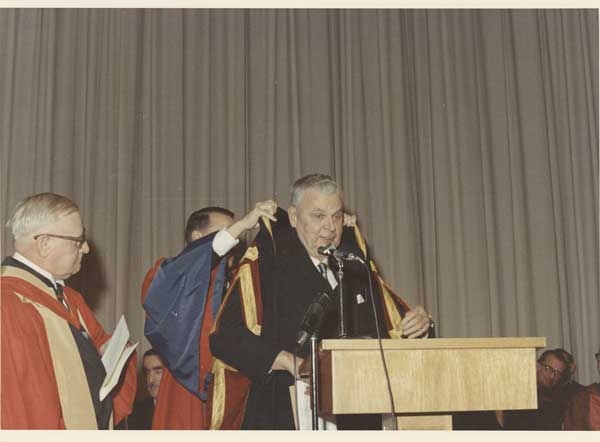

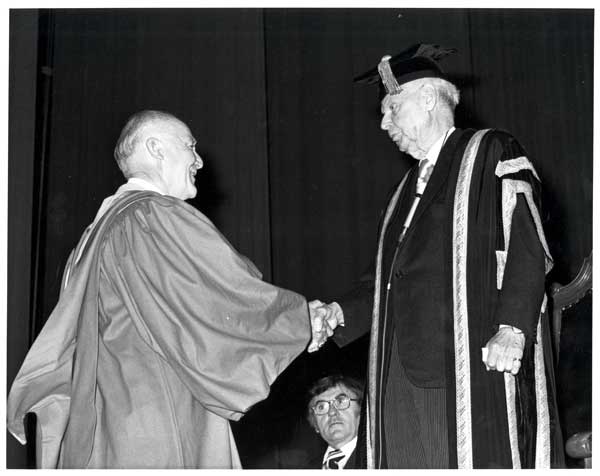

For seven decades Diefenbaker maintained close relationships with the UofS community. He served on the University Senate from 1932 until 1950, and he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Civil Law.

In his memoirs, Diefenbaker commented that the University newspaper, “The Sheaf,” predicted that he would be Leader of the Official Opposition in forty years — a projection that was only off by one year.

The Chancellor's Legacy

It was in 1969, during his installation as Chancellor of the University of Saskatchewan — a position he held until his death — that Diefenbaker announced his intention to bequeath all of his papers and personal possessions to the University. On 20 September 1975, Diefenbaker himself turned the sod that began the construction of The Diefenbaker Centre. The building officially opened on 12 June 1980.

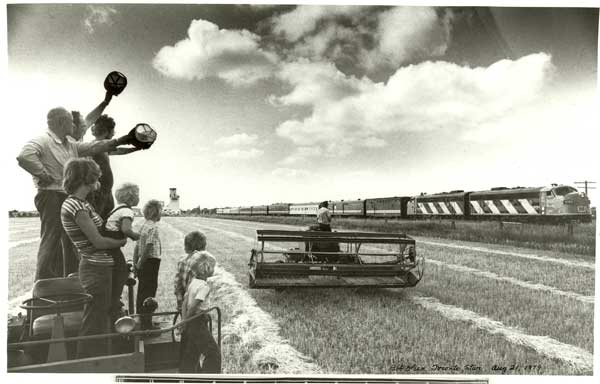

Diefenbaker's final request was that he be buried on the UofS campus. After his death, his body was transported by rail from Ottawa to Saskatoon. As the train traveled across the country, people lined the tracks to pay final tribute to Canada's 13th Prime Minister. Diefenbaker and his second wife Olive are interred behind the Diefenbaker Centre overlooking the South Saskatchewan River.

|

|

|

Pursuit of Office

A Man of the People

"You have no idea what it means to come out here and be addressed by my first name. I tell you this is something that money can’t buy." -Prince Albert, Sask, 27 April 1962

The Perennial Candidate

Diefenbaker's determination carried him through many personal and political setbacks.

His first disappointment came in 1925 when he was defeated in his election bid to represent Prince Albert in the House of Commons. He tried for the same seat again in a 1926 by-election, this time losing to Prime Minister Mackenzie King.

Deciding to test the political waters provincially, in 1929 Diefenbaker became a contender for MLA under the banner of the Saskatchewan Conservative party. He lost again, but this time only by a narrow margin.

In 1933 Diefenbaker turned to local politics, running in the mayoral election in Prince Albert, where he was beaten once more. It was not however, in Diefenbaker’s character to give up.

"Mother gave me drive, father gave me the vision to see what could be done." -One Canada: Memoirs of the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker

Resolute Determination

Finally, in October of 1936, Diefenbaker threw his hat into the provincial Conservative leadership race and emerged triumphant. The victory, however, was hollow; the Conservative party was unable to win a single legislative seat in the 1938 provincial election.

Diefenbaker returned to the federal arena and in 1940 was rewarded by the constituents of Lake Centre with a seat in the House of Commons. Two years later, he ran for the leadership of the federal Conservative party and came third to John Bracken (who changed the party name to the Progressive Conservative Party). More determined than ever, Diefenbaker sought the leadership of his party in 1948, this time losing to Ontario Premier George Drew.

“I never once regarded a defeat as a termination. I have been beat often, but I have never been spiritually vanquished. The day after a defeat at the polls, I was always back at work. I never feel hurt or whipped.” -Library, Saskatchewan. April 1960

Making History

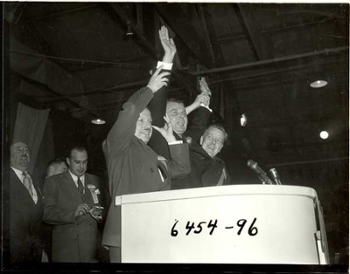

In 1957, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent called an election for the 10th of June, leaving Diefenbaker, who had just been elected the Leader of the Official Opposition, a mere five months to prepare. Initially, the Liberals were not concerned about Diefenbaker, who had lost countless elections.

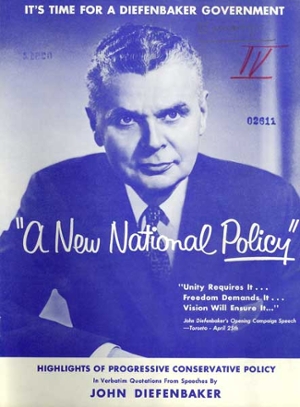

However, running under the slogan, “It’s time for a Diefenbaker government,” Diefenbaker’s dramatic speaking style appealed to western farmers and workers, many of whom had felt increasingly marginalized by the Liberal government. To everyone’s surprise, the election ended with the Progressive Conservatives winning a minority government over the Liberals.

Despite being made up of an inexperienced group of MPs, during their first term in power, the Diefenbaker Government proceeded to pass progressive social legislation. Several of Diefenbaker’s first appointments to Parliament also demonstrated his commitment to equal rights.

“I've lived history, I've made history and I know I'll have my place in history. That's not egoism.” -"Maclean's Magazine", January 1973

An Inclusive Canada

Envisioning One Canada

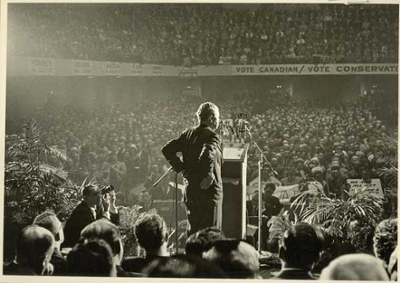

When another election was called in 1958, the Liberals were confident in being able to regain Parliament, but they had underestimated the support that Diefenbaker had secured in less than a year. This time, Diefenbaker focused on national development and his vision of “One Canada” – a programme that assured Canadians in every region a share in the country’s prosperity. Diefenbaker’s appeal was undeniable and thousands flocked to his rallies.

“One Canada... where Canadian will have preserved to them the control of their own economic and political destiny.” -Winnipeg, MB, 12 February 1958

On 31 March 1958, Diefenbaker led the Progressive Conservatives to a landslide win over the Liberals. Based on a percentage of total seats in the House of Commons, Diefenbaker’s victory remains the largest in Canadian history.

More importantly to Diefenbaker, he finally had his chance to make his lifelong dream of creating a Canadian Bill of Rights a reality.

|

|

|

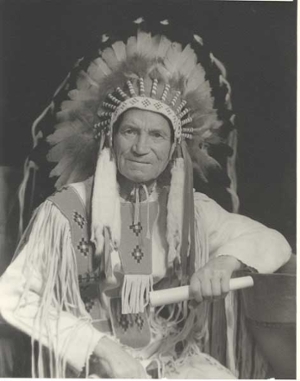

The Enfranchisement of First Nations

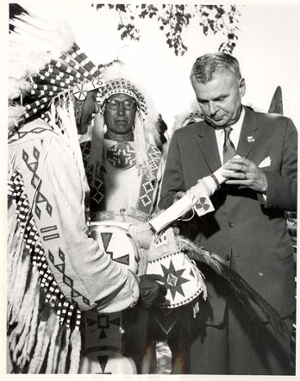

Diefenbaker’s key achievement in Aboriginal affairs was the extension of the franchise to First Nations, in 1960. Previous to this, Indigenous peoples could only vote in federal elections if they first gave up their Indian Status. By altering a section of the Indian Act, the Diefenbaker government ensured that all Indigenous peoples could participate in elections.

Enfranchisement, however, was looked upon with suspicion by Indigenous peoples who associated voting with the loss of their status and rights. In response, the Diefenbaker government made assurances that being enfranchised would not jeopardise Indigenous rights in any way. At the 1962 election, First Nations went to the polls for the first time and in greater numbers than expected.

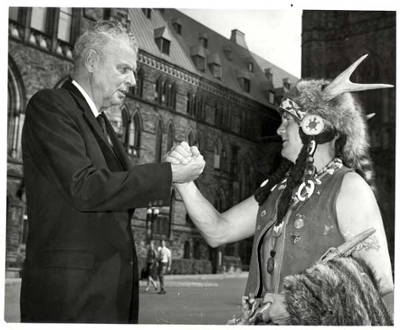

Diefenbaker continued his efforts to create harmony between the federal government and Indigenous peoples throughout his political career. His amicable relationships with First Nations resulted in honourary memberships in several communities.

|

|

|

Diverse Representation

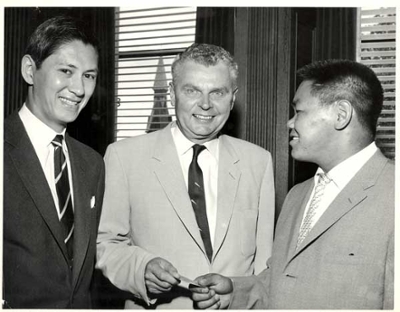

As Prime Minister of Canada, Diefenbaker was determined that his cabinet and caucus would include ethnic minorities and others who had been historically disenfranchised from the political process. Ellen Fairclough

Ellen Fairclough

Member of Parliament: Hamilton West, 1950-1963

Historical Significance: The first female Canadian Federal Cabinet Minister.

Parliamentary Responsibilities:

- Secretary of State of Canada, 1957-1958

- Acting Prime Minister, 19-20 February 1958

- Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, 1958-1962

- Postmaster General, 1962-1963

Michael Starr

Michael Starr

Member of Parliament: Oshawa, 1952-1968

Historical Significance: The first Canadian Cabinet Minister of Ukrainian descent.

Parliamentary Responsibilities:

- Minister of Labour, 1957-1963

- Acting Leader of the Opposition, September-November 1967

- Progressive Conservative Party House Leader, 1965-1968

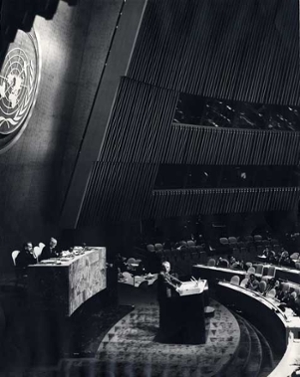

Douglas Jung

Douglas Jung

Member of Parliament: Vancouver Centre, 1957-1962

Historical Significance: As the first Canadian Member of Parliament of Chinese descent, Douglas Jung introduced legislation granting amnesty to illegal immigrants from Hong Kong. He also represented Canada as Chairman of the Legal Delegation to the United Nations.

James Gladstone

James Gladstone

Member of the Senate: 1958-1971

Historical Significance: First Aboriginal person appointed to the Senate.

Parliamentary Responsibilities:

- Appointed Co-chair of the join Senate-House of Commons committee in charge of Indian Affairs (May 1959). He was responsible for examining the social and economic status of Aboriginal people in Canada.

The Commonwealth of Nations

In 1931, Britain formally established legislative equality between all self-governing dominions and the United Kingdom. The resulting Commonwealth of Nations, with Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II as its head, consisted of countries that had once been colonies of Britain. The leaders of these states met to discuss issues of mutual and international importance. Although these nations have diverse social, economic and political backgrounds, they also have identified shared common values and goals. These include the advancement of multilateralism, individual liberties, egalitarianism, democracy and human rights – concepts that the Diefenbaker government promoted and supported.

A commitment to domestic independence put the members of the Commonwealth in an awkward position with regards to South Africa’s practice of racial segregation. Following a referendum in 1960 (in which only whites could vote) South Africa became a republic. This change in status required a reapplication for membership in the Commonwealth of Nations, and brought the question of apartheid to the forefront of the discussions at the 1961 Commonwealth conference.

Opposing Apartheid in South Africa

Following World War II, countries around the world began to move away from policies of racial discrimination and segregation, but this was not the case in South Africa.

Beginning with the election of the National Party in 1948, the government of South Africa took formal steps to separate people of color, including politically and physically segregating South Africans based on race. This strategy of "apartheid" (an Afrikaans word meaning "separateness") was a legalized system designed to keep those of European descent politically and economically dominant, while institutionalizing racial intolerance.

Under the Diefenbaker government, Canada was one of the first countries to take the lead in openly opposing Apartheid.

| Disproportionate Treatment Table, ca. 1978 | Blacks | Whites |

| Population | 19 million | 4.5 million |

| Land Allocation | 13% | 87% |

| Share of National Income | <20% | 75% |

| Infant Mortality Rate (Urban) | 20% | 3% |

| Infant Mortality Rate (Rural) | 40% | 4% |

| Annual Expenditure on Education per Pupil | 45 rands ($57.15 CDN) | 696 rands($883.92 CDN) |

| Teacher to Pupil Ratio | 1 per 60 students | 1 per 22 students |

| Doctors to Number of Patients | 1 per 44,000 | 1 per 400 patients |

| Minimum Taxable Income | 360 rands ($457.20 CDN) | 7,500 rands ($9,525 CDN) |

| Ratio of Average Earning | 1/14 | 1 |

| Source: Leo80 |

Standing Apart on Apartheid

Diefenbaker seldom backed down on matters he considered moral imperatives. In 1961, the Diefenbaker government stood with its Asian and African counterparts in condemning apartheid and formally opposing the renewal of South Africa's membership in the Commonwealth. Ultimately, rather than face the judgment of member states, South Africa withdrew its application for readmission into the Commonwealth of Nations.

"Apartheid has become the world’s symbol of discrimination. I took the position that if we were to accept South Africa’s request [for readmission] unconditionally, our action would be taken as approval or at least condonation of racial policies, which are repugnant to and unequivocally abhorred and condemned by Canadians as a whole." -House of Commons, 17 March 1961

International Impact

Following the Conference, non-Commonwealth countries and independent organizations followed the Commonwealth of Nations in condemning South Africa’s policies.

The United Nations placed trade sanctions on South Africa, thereby limiting trade between that country and UN member states. However, these actions proved ineffective in halting the South African government’s institutionalized practices of repression, banishment, torture, imprisonment for life, and executions.

Although trade embargoes gradually isolated South Africa from the rest of the world, the nation's government refused to eliminate their Apartheid policies until 1994.

|

|

U.S. Relations

John and Ike: The "Diefen-hower" Years

"...Presidnet Esienhower and I were from our first meeting on an 'Ike-John' basis... we were as close as the nearest telephone." -One Canada: Memoirs of the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker-

Canada-U.S. relations, particularly the working and personal interactions between Canadian Prime Ministers and American Presidents, have always been an important matter to both countries.

From their first meeting, Diefenbaker and President Dwight Eisenhower, who was the U.S. President for the majority of the time Diefenbaker served as Prime Minister, enjoyed a positive relationship. The two men had spent their youth in similar Western farming communities and their political and economic policies were closely aligned. Almost the same age, and both having served in the military, the two heads of state also shared many personal values.

Even their wives became good friends. The respect that Diefenbaker and Eisenhower had for each other was reflected in Canada-U.S. relations during this time.

Fallout on the 49th Parallel

Compared to his close association with Eisenhower, Diefenbaker’s relationship with John F. Kennedy was frosty. From the time Kennedy took office in 1961 until the end of Diefenbaker’s term as Prime Minister, the situation continued on a downward spiral. Never before had relations between a Canadian Prime Minister and an American President been as strained as they were between 1961 and 1963.

Mr. Diefenbaker Goes to Washington

The tensions between Diefenbaker and Kennedy were apparent from their first official meeting in Washington. While Diefenbaker and Eisenhower had shared many political perspectives, Kennedy and Diefenbaker clashed frequently.

The men had decidedly different personalities, temperaments, and political ideologies. Kennedy saw Diefenbaker as a leader who had trouble connecting with a younger generation of voters. Diefenbaker attributed Kennedy’s political success to a privileged background and personal connections rather than to genuine support.

"I would like to announce that I have invited the Prime Minister of Canada the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbawker [sic] to make a brief visit to Washington on Monday, February 20th, for discussion of matters of mutual interest to our two countries." -President John F. Kennedy announcing John Diefenbaker’s official visit to the U.S., 8 February 1961

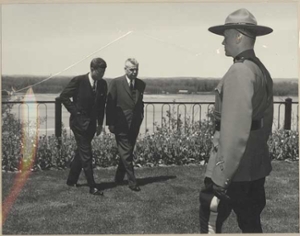

Mr. Kennedy Goes to Ottawa

Kennedy’s behaviour during his first visit to Ottawa on 16 May 1961 did little to change Diefenbaker’s opinion of him. In his speech, Kennedy twice mispronounced Diefenbaker’s name, then drew attention to the Prime Minister’s halting use of French by joking, “I am somewhat encouraged to say a few words in French from having had a chance to listen to the Prime Minister.”

After their meeting, Diefenbaker discovered a memo that Kennedy had forgotten titled, “What we want from the Ottawa trip.” It advised Kennedy to “push” Diefenbaker in four policy areas, including the placement of American nuclear missiles in Canada. Diefenbaker perceived the communication as another example of Kennedy’s bulling. Diplomatic protocol required that the memo be returned to the American embassy, but Diefenbaker kept it, and made sure that Kennedy knew it.

"The Cuban Missile Crisis" Canadian Challenges to U.S. Responses

On 15 October 1962, Kennedy was informed that Soviet missile installations had been discovered in Cuba. For a week, Kennedy was cloistered in confidential discussions with his twelve most trusted government advisors. When he finally alerted other nations to the “Cuban Missile Crisis,” the American Strategic Air Command had already placed all U.S. forces on "Defense Condition 2" ("Defcon2"). This was the highest state of military readiness — only one step away from nuclear war. Kennedy had expected unconditional support from the Canadian government, but Diefenbaker refused to immediately commit Canadian forces.

On 15 October 1962, Kennedy was informed that Soviet missile installations had been discovered in Cuba. For a week, Kennedy was cloistered in confidential discussions with his twelve most trusted government advisors. When he finally alerted other nations to the “Cuban Missile Crisis,” the American Strategic Air Command had already placed all U.S. forces on "Defense Condition 2" ("Defcon2"). This was the highest state of military readiness — only one step away from nuclear war. Kennedy had expected unconditional support from the Canadian government, but Diefenbaker refused to immediately commit Canadian forces.

Ultimately, global nuclear war was averted, but Diefenbaker was incensed at what he perceived as Kennedy's arrogance.

"I knew that President Kennedy... thought he had something to prove.... I considered that he was... capable of taking the world to the brink of thermonuclear destruction to prove himself the man for our times, a courageous champion of Western democracy." -One Canada: Memoirs of the Right Honourable John G. Diefenbaker

The Bomarc Missile Controversy

Bomarcs were supersonic, surface-to-air, long-range missiles capable of carrying nuclear warheads. They were designed and produced by the U.S. as anti-aircraft weapons to intercept and destroy Soviet bombers before they reached North America. For the system to be entirely effective, some of the missiles had to be installed at strategic locations in Canada.

In 1958, Diefenbaker hesitantly agreed to deploy 56 Bomarcs in Ontario and Québec. He made efforts to ensure they would only be employed for defensive action and that the Americans could not launch them without Canadian consent.

“The sole authority to authorize the use of those weapons in Canada would be the Prime Minister… who… would… give directions as to when and how they should be actually used.” -Minister of National Defence, Major General George Pearkes addressing Parliament, 5 August 1960

When Diefenbaker’s government installed the Bomarcs in 1958, they did not make in known the Canadian public that the missiles were to be fitted with nuclear warheads. When this detail surfaced in 1960, fierce public opposition arose over the presence of nuclear weapons on Canadian soil. Losing support, the Progressive Conservatives withdrew their commitment to the program, but the damage had been done – Diefenbaker’s cabinet split over the dispute. The government was forced to call an election in 1963 and lost to Lester B. Pearson.

“The Pearson policy is to make Canada a decoy for international missiles.” -Winnipeg, Manitoba, March 1963

The Liberals deployed the first nuclear-armed Bomarcs during the same year as Pearson’s electoral win.

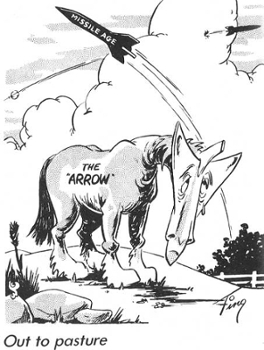

Avro Arrow

Arrows of Misfortune

In the late-1940s, the Soviet Union developed jet-powered, long-range bombers capable of transporting nuclear weapons throughout Europe and across North America. As a counter-measure, Western nations began producing missile-armed interceptors. Research and design on Canada’s version – the Arrow – began in 1953. Avro Aircraft Ltd. was the Canadian company charged with building the delta-winged aircrafts.

|

|

Minister of National Defence, Major General George Pearkes initially remarked that the Arrow was a “…symbol of a new era for Canada in the air.” However, keeping ahead of rapidly emerging technology meant constant modifications to the jet’s design, which in turn necessitated increased staff and funding. By 1955, the project had grown so large that it employed over 41,000 people and cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

Bowing to Pressures

In 1957, bowing to pressures from the Americans, Diefenbaker’s government committed to a partnership with the U.S. in NORAD (North American Air Defense). In order to provide an early warning and defence system, NORAD combined Bomarc missile technology with SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment), an early computerized system for tracking and intercepting bombers.

Joining NORAD placed incredible financial burdens on Canada’s economy. Skyrocketing production costs combined with increasingly rapid international advancements in offensive nuclear technologies ultimately doomed the Arrow.

Grounded: The End of a Dream

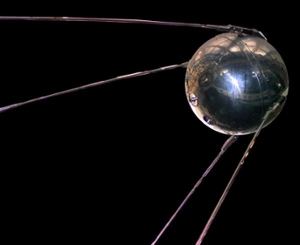

On 4 October 1957, the first Arrow finally rolled off the production line. That same day the Soviet Union unveiled Sputnik 1, the first satellite to enter earth’s orbit. Sputnik’s launch marked the beginning of the “Space race” and it challenged conventional thinking about what forms of military defenses were effective in the Cold War. The world was suddenly faced with space and missile technology that seemed to make the distance separating continents and countries irrelevant. In this climate, purchasing the Bomarc missile seemed wiser than developing costly fighter jets.

On 20 February 1959, the Diefenbaker government cancelled the Arrow program. A total of $470 million had been spent on planes that never flew and 14, 528 Avro employees lost their jobs.

“We did not cancel the [Arrow] CF-105 because there was no bomber threat, but because there was a lesser threat and we got the Bomarc in lieu of more airplanes….” -Minister of National Defense, Major General George Pearkes

|

|

Pointing Arrows

Diefenbaker and his government faced ruthless condemnation following the scrapping of the Arrow. Many blamed Diefenbaker for having single-handedly destroyed the program. Some argued that the sophisticated Arrow would have contributed to the national development and international prestige of Canada.

In truth, the Liberal government had already considered discontinuing the Arrow program before losing the 1957 election to the Progressive Conservatives. Unfortunately, it was Diefenbaker who inherited the costly set-backs that had plagued the jet’s development.

A New Flag

The Great Flag Debate

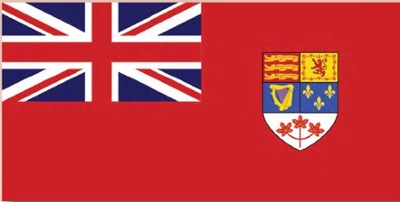

In 1963, Lester Pearson succeeded Diefenbaker and became Canada’s fourteenth Prime Minister. The following year, he proposed replacing the Red Ensign with a flag that would promote national unity. Considering Diefenbaker’s commitment to his vision of promoting “One Canada,” some might think it surprising how passionately he argued against Pearson’s idea. “The Great Canadian Flag Debate,” as it came to be called, split the nation.

It is interesting to note that, even though the Red Ensign was used widely from the time of Confederation until 1965, it was never actually approved as Canada’s national flag. The Union Jack was the official standard of the country and was a symbol of Canada’s membership in the Commonwealth.

“Sir, a flag cannot be created by one man however powerful his position. Flags are born in the strife and turmoil of the clash of history. They are not the result of egocentric decision.” -John Diefenbaker, 1 September 1964

A Tattered Flag: Retiring the Red Ensign

Pearson’s Liberal government argued that a new flag would assert Canada’s sovereignty and demonstrate that the nation was no longer a British colony. Those opposing Pearson felt strong attachments to the Red Ensign as an important historic symbol of Canada’s roots. Following a summer of fruitless parliamentary debates, Pearson formed a committee with the mandate to design a new standard.

After receiving thousands of suggestions from Canadians, the committee narrowed the possibilities to three: the Red Ensign; a second design created by George Stanley with a single red maple leaf on a white background with red bars on both ends; and a flag with three maple leaves and two blue bars on each side (nicknamed the “Pearson Pennant”).

"The Maple Leaf"

Ultimately, Lord Stanley’s design was chosen. The “Maple Leaf” as it was dubbed, was brought to the House of Commons for a vote. Despite last-ditch efforts by the Progressive Conservatives to sway the House, the flag was approved. The new standard was raised over the Parliament Building on 15 February 1965.

Diefenbaker bitterly charged Prime Minister Pearson with having “done more to divide the country than any other prime minister” and he never accepted Canada’s new flag. For his funeral in 1979, his coffin was draped with both the Red Ensign and Canadian Maple Leaf.

|

|